Tren de Aragua, Venezuela’s largest homegrown gang, has become a transnational criminal threat. With expertise in migrant smuggling, human trafficking, and extortion, the group has followed the exodus of Venezuelan migrants and found ways to set up permanent operations in several Latin American nations. Its latest victim is Chile, where the Tren de Aragua has become a significant security concern.

On the streets of Bolivia’s largest city, Santa Cruz, a couple was cleaning car windows and selling sweets, with their daughter in tow, as they had done every day since arriving in early 2022. But that day, the husband left his wife and daughter alone for a few hours. When he returned, they were both gone.

His first assumption was a reasonable one: His family had probably been detained by Bolivian authorities for being undocumented, the news outlet El Deber reported. But as he asked other Venezuelan street vendors if they had seen anything, nobody had.

SEE ALSO: Tren de Aragua Profile

His search grew ever more desperate for the next few days. That’s when the Tren de Aragua got in touch. A source in Bolivia with knowledge of the case, who asked not to be identified for security reasons, told InSight Crime about how the gang reeled him in. They told the man his family had been kidnapped and sent to Chile. If he wanted to see them again, he would have to move cocaine from Bolivia into Chile in a double-bottomed suitcase. With no other recourse, the man agreed.

He didn’t get far.

He was arrested by authorities at the central city of Oruro, on the way to Chile, and remains in pre-trial detention. The whereabouts of his wife and daughter are still unknown.

This type of nightmare scenario has become increasingly common for Venezuelan families in Bolivia. InSight Crime documented similar cases in the cities of Santa Cruz, La Paz, Cochabamba, Oruro, and Pisiga. According to the investigation by El Deber, the Tren de Aragua is systematically preying on undocumented migrant women in vulnerable conditions, bringing them to Chile, and sexually exploiting them.

Chile’s Response

Chilean authorities have made this one of their foremost security priorities. In mid-July, Javier García, the mayor of Colchane, a village on the country’s border with Bolivia, confirmed that the Tren de Aragua moves people, drugs, and weapons into Chile near his village. Last March, prosecutors in Chile’s northern border region of Tarapacá reported that Tren de Aragua cells have been connected to homicide, kidnapping, migrant smuggling, and trafficking of persons for sexual exploitation and extortion.

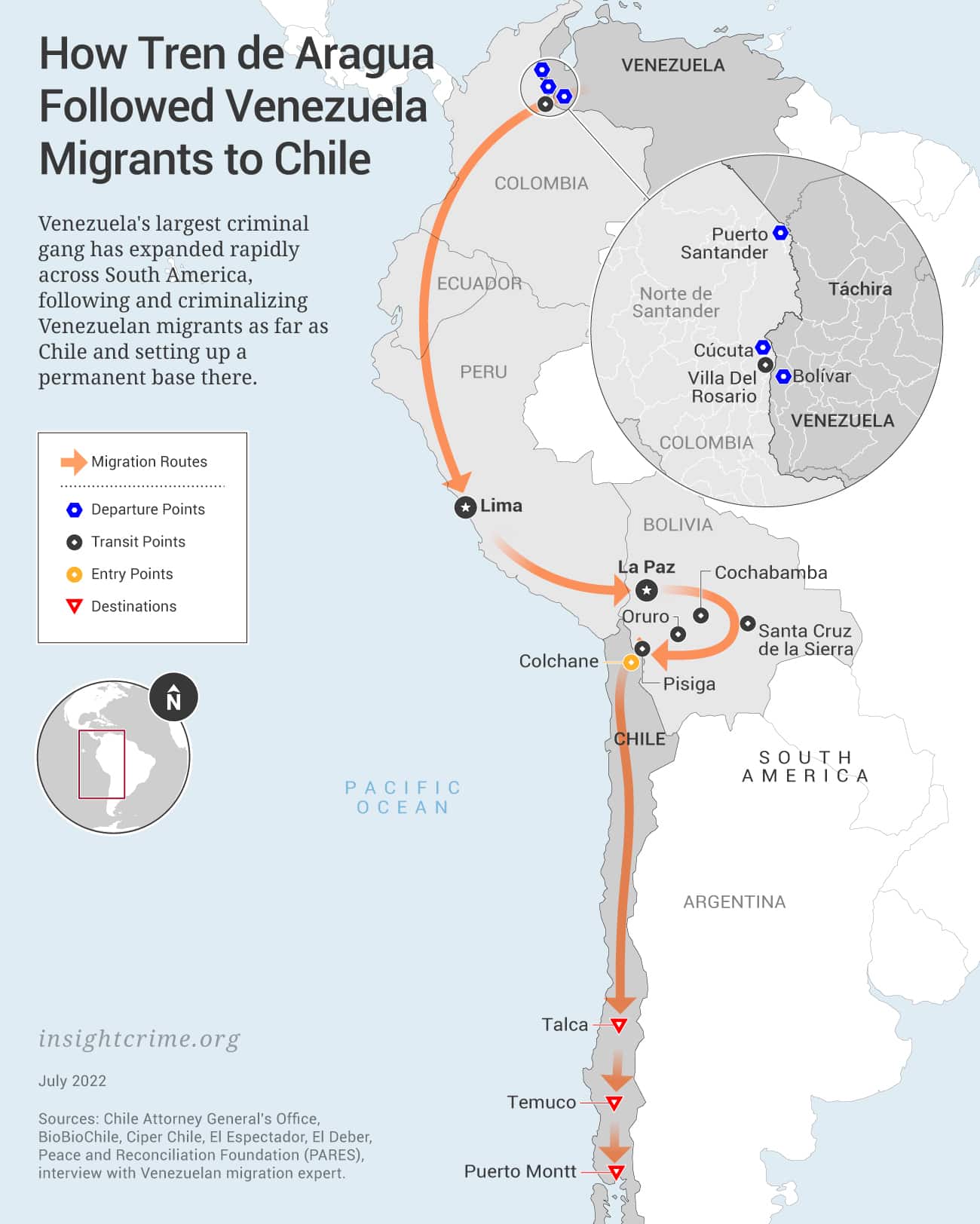

Chile has become the southernmost stop for the Venezuelan gang, which has already expanded its reach through Colombia, Peru, and Bolivia. As Chile is a target destination for thousands of Venezuelans, the Tren de Aragua likely made the country a priority.

The Tren de Aragua’s expansion into Chile has extended a network of human smuggling routes that the group has either set up or taken over, and which starts much closer to home.

Countries of Origin: Colombia and Venezuela

Tren de Aragua has successfully muscled in on crowded criminal turf. While several rivals had already set up operations at the Colombia-Venezuela border, Tren de Aragua has carved out a niche along remote trails crisscrossing the frontier. It helps migrants, usually undocumented Venezuelans, to cross into Colombia. But while many migrants pay for their services and are free to go, others are coerced into crippling debt, forced to carry drugs, or kidnapped for sexual trafficking.

“In cities like Cúcuta [an important border city in Colombia], there are people who arrange the whole trip. They plan the routes across the borders that reach countries like Peru. They help people move along the trails. But they also abduct [victims], particularly minors. All the complaints I have received involve the Tren de Aragua,” an expert in migratory issues working on the Colombian-Venezuelan border, who asked to remain anonymous for security reasons, told InSight Crime.

Migrant smuggling, moving people voluntarily across national borders, and human trafficking, where victims are detained against their will or coerced into exploitation, are intricately linked.

In March 2022, a gang affiliated with the Tren de Aragua was dismantled in Puerto Montt, a port city in southern Chile. According to prosecutors, it received Venezuelan women trafficked by the gang from Colombia and Venezuela. While they went to Chile willingly, once they arrived in cities such as Puerto Montt, Talca, and Temuco, they were told they owed insurmountable debts, which had to be paid in sexual services. As evidenced in the Bolivia case, men can also be coerced to traffic drugs to guarantee their family’s safety.

The precarious conditions of Venezuelan migrants offer multiple revenue streams to the Tren de Aragua.

Interconnected Networks

To keep a tight grip on migrants moving from Venezuela to Chile, the Tren de Aragua has built up an interconnected network of coyotes (human smugglers) and smaller criminal gangs, which help to receive, abduct and criminalize migrants.

“What exists is a network out of Venezuela that traverses Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia before finally reaching Chile. They are interconnected, supporting each other, receiving migrants from different areas, and channeling them to the places where they are headed. It is not a national network, but rather an international network, dedicated to this,” Hardy Torres, deputy chief prosecutor in Chile’s northern province of Tamarugal, told media outlet Ciper.

SEE ALSO: GameChangers 2020: Tren de Aragua and the Exportation of Venezuelan Organized Crime

In Colombia, the Ombudsman’s Office (Defensoría del Pueblo) has reported that the Tren de Aragua recruits and transfers migrants with help from the Rastrojos, a Colombian criminal group, which controls border trails in the department of Norte de Santander.

In Peru, media outlets have reported on human trafficking networks involving Venezuelan citizens, which pay the Tren de Aragua so that they are permitted to force trafficking victims into prostitution in areas controlled by the gang.

“The Tren de Aragua is involved in extorting the hostels with sex workers, small traders, and motorcycle taxi drivers. They extort them in exchange for security. This used to be done by the Peruvian and Colombian gangs that controlled the area, but now it is the Tren de Aragua. There is confirmation that they control the districts of Independencia and San Martín de Porres in the city of Lima,” Jaime Antezana Rivera, an organized crime and drug trafficking investigator in Peru, told InSight Crime.

In the case of Bolivia, the “trocheros” or coyotes that offer to help migrants cross in exchange for money, are found in Pisiga, an urban town, located on the country’s border with Chile. The Tren de Aragua controls these irregular border crossings on the Bolivian side, and across the border, in Colchane.

However, the group’s expansion has been so rapid and has covered so much ground that there are doubts as to how much control the Tren de Aragua’s leader, Héctor Rusthenford Guerrero Flores, alias “Niño Guerrero,” can exert over operations in Chile from his base in Venezuela’s Tocorón prison. InSight Crime has not yet confirmed the extent of contacts between Chilean cells and Tocorón, or whether the Tren de Aragua’s operations in Chile are franchised to smaller groups involving Venezuelans.

Northern Chile: The Entry Point for Migrants

The four regions of northern Chile – Arica and Parinacota, Tarapacá, Antofagasta, and Atacama – have become the gateway for irregular migrants looking for a new life.

Police statistics showed that registered irregular entries by migrants in these regions soared from 2,905 in 2017 to 56,586 in 2021. Most of these arrived in Tarapacá, especially around the border crossing of Colchane.

According to Pilar Lizana, a researcher and security expert at Chilean think tank, AthenaLab, the Tren de Aragua has focused on moving migrants from Pisiga in Bolivia to Colchane due to the lack of security and the porous nature of this extensive desert area.

Unfortunately, this has led to other severe consequences. In 2021, Chile’s national homicide rate dropped by 25 percent to 3.5 per 100,000 residents, but in Tarapacá, it increased by 183 percent to 9.7 per 100,000. And that figure could still be an underestimate.

“We are witnessing an increase in homicides, with 60 percent now involving a firearm and 70 percent being due to score-settling [between criminal gangs],” explained Lizana. She added that the wave of violence was likely due to a fight for control of Tarapacá and its human smuggling routes.

The Tren de Aragua is undoubtedly in an excellent position to brutally defend its turf, if need be. It has proven its willingness to do so at home, with dozens of killings attributed to the group in Venezuela, as well as in Colombia.