After a decade of lightning growth in membership and territory, the CJNG’s reign as Mexico’s most dominant and ruthless cartel may be showing the same signs of wear that foreshadowed the downfall of its many predecessors.

A formidable force and present in most of the country, the Jalisco Cartel New Generation (Cartel Jalisco Nueva Generación – CJNG) is now facing challenges on multiple fronts. Concerns over the health — and perhaps even death — of all-powerful leader Nemesio Oseguera Cervantes, alias “El Mencho,” who has not been seen for years, are prompting once loyal groups to breakaway, while internal disharmonies have come to a bloody head along a vital drug trafficking route in northern Michoacán.

Meanwhile El Mencho’s birthplace, the town of Aguililla, has become the focal point in a deadlocked ground war, as rival cartels allied against the Jalisco Cartel stall its offensive and squeeze it from all sides.

This unprecedented attack on the supremacy of the CJNG, considered by the US Department of Justice to be “one of the five most dangerous criminal organizations in the world,” draws a comparison between the mega cartel and the many others before it that have groaned and then collapsed under their own weight, like the Zetas, the Beltrán-Leyva Organization (BLO) and the Tijuana Cartel.

Are the CJNG’s troubles proof that even the most powerful of Mexico’s criminal organizations eventually succumb to success and greed, or nothing more than the inherent dynamics of a violent crime gang writ large?

Here, InSight Crime looks at the three major flashpoints that are producing cracks in the armor of the CJNG.

The Mezcales in Colima

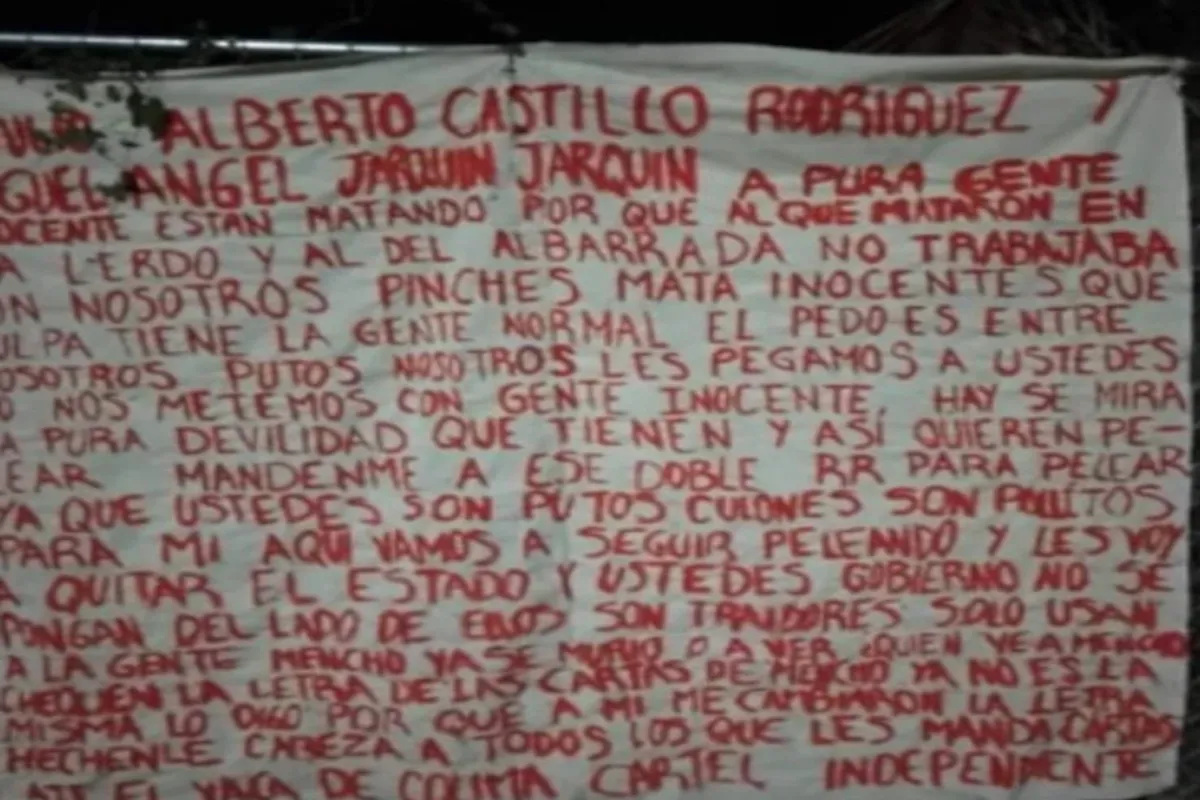

In early 2022, a series of “narcomantas” appeared around the city of Colima, in the state of the same name. The messages, penned by a smaller local group, made a bold claim: El Mencho had suffered a cardiac arrest and was dead.

The group making the claim was the Mezcales (also known as Cartel Independiente de Colima), presumably headed by José Bernabé Brizuela Meraz, alias “La Vaca.” Until this point, the Mezcales had acted as the CJNG’s local enforcers, working under the larger cartel’s direction. But without El Mencho at the helm, La Vaca believed the Jalisco Cartel had been stripped of respect and status, and he no longer felt obliged to give his former employer devotion. Now, he wanted control.

“I owe respect and loyalty only to El Mencho,” La Vaca is reported to have said when declaring his decision.

In late January, the bullets began to fly. Colima witnessed an explosion of violence as fighting broke out over control of the state, which clings to Mexico’s western coast and, though small, is strategically important for organized crime. Colima’s port, Manzanillo, is a major arrival point for chemical precursors, and the state also borders Jalisco — the seat of the Jalisco Cartel’s power —and Michoacán, a predominantly agricultural state that has long been a drug trafficking hub.

Skirmishes lasted for over a month and at least 60 people were killed, La Jornada reported. In response to the violence, over 2,000 soldiers and members of the National Guard were sent to the state.

The claims of El Mencho’s demise were foundational to this bloodletting, but their reliability is questionable.

The leader’s disappearance has certainly generated suspicions of his passing. He has not been seen in public for some time, and he is understood to be ill, most likely with a kidney disease. In July 2020, Mexican authorities located a hospital in Jalisco that is believed to have been built by the CJNG to garner support from locals and to provide a secure medical unit in which the cartel leader can receive care.

So far, authorities have refused to confirm El Mencho’s death, stating only that “there is no reliable information” that proves the rumors. No body has been located, and he remains on the US Drug Enforcement Administration’s (DEA) Most Wanted list.

Reports of his death, fueled by the lack of sightings, have circulated for at least two years. But according to Prensa Libre, the main proof offered by the Mezcales was that the handwriting on notes allegedly penned by El Mencho had changed. Alleged plaza bosses and sicarios also paid tribute to the apparently fallen leader on social media, and messages referring to an “heir” arriving shortly were also shared, La Voz De Michoacán reported.

Mike Vigil, the former chief of the DEA’s international operations, told InSight Crime that rumors of El Mencho’s demise are unfounded, though he believes that the crime boss is sick.

“Many Mexican drug traffickers have faked their own deaths and have spread rumors to take the heat off of them,” he told InSight Crime. “When criminals have health issues and are on the run from both security forces and rival cartels, they can’t get the medical attention that they usually would. Ismael Zambada García, alias “El Mayo,” is a diabetic but refuses to come out of the mountains for treatment for fear of capture.”

The Pájaros Sierra on the Jalisco-Michoacán Border

The sharp crack of gunfire that cut through the calm of a Sunday afternoon in Mazamitla, Jalisco ended the lives of three sicarios and signaled the willingness of emerging criminal organizations to stand up to the might of the CJNG.

The shootout on May 1 between the Jalisco Cartel and a group, which the Mexican government dubbed Pájaros Sierra, was just one of several battles that took place earlier this year in towns along a vital drug trafficking highway between Morelia, Michoacán and Guadalajara, Jalisco.

So new is the group that its name has not yet been confirmed. The media often refers to the group as the “Pájaros de la Sierra,” but InSight Crime investigators have found that residents of towns where fighting broke out are not familiar with it.

The moniker chosen by the Mexican government may not be linked to any title the group itself uses, said Alejandro Hope, a security analyst. In fact, emerging groups are often given names by the government in order to impose a narrative on otherwise chaotic and frightening events, he said.

“It creates a notion that this is a highly structured, vertically-integrated criminal organization that has a clear identity,” Hope said.

However, there is one element in the group’s story that everyone seems to agree on: its alleged involvement in the apparent massacre of 17 CJNG members at a funeral in San José de Gracia, Michoacán in February.

As InSight Crime reported at the time, the massacre was the result of a long-running feud between regional CJNG leaders.

The Mexican government alleged that the Pájaros Sierra were the gunmen in the massacre, and the CJNG later released threats that promised revenge against the group for their part in the killings. These threats were not idle; the apparent murder of the Pájaros Sierra leader, “Palillo,” was later reported by La Opinion.

On May 5, the arrest of eight alleged members of the Pájaros Sierra for their part in the funeral killings was announced.

Despite the appearance of this new and violent faction and its role within cartel infighting, the CJNG’s message remains firm, said Mike Vigil. The Jalisco Cartel’s swift response against Palillo demonstrated it still operates in a top-down fashion, and demands complete loyalty. Those who try to break that structure face severe consequences.

“Unlike the Sinaloa Cartel where the decision-making process runs across the line, the CJNG has a hierarchical structure: El Mencho runs it like an autocrat and his orders must be obeyed without question. If a person contradicts an order it is an automatic death sentence; the Jalisco Cartel has a clear internal mandate,” he said.

SEE ALSO: US, Mexico Sanctions Offer Insights Into CJNG Hierarchy

Yet the arrival of the so-called Pájaros Sierra underscores the kind of insurgent opposition it faces in several regions. Unlike the Sinaloa Cartel, which can draw on regional patriotism for legitimacy in certain areas, the CJNG cannot claim any form of kinship in most of the regions it operates in. Instead, it must rely on brokering alliances with local actors and weaker cartels in areas it seeks to control.

“In some ways it’s a misnomer to say the CJNG is a cartel. [Like the CJNG], most cartels are a coalition of regional organizations or cells that use the label but are not tied within a structure to leadership,” said Hope.

The Correa and Cárteles Unidos in Southern Michoacán

In southern and eastern Michoacán, the CJNG’s all-out attack for control has been halted, and it is now engaged in multiple draining conflicts that have reached bitter stalemates. Here, the fighting has been so vicious that the use of military-grade weaponry including “narco-tanks,” IEDs and rocket launchers, has become commonplace, InSight Crime reported in early March.

Part of this is related to geography: the south Michoacán town of Aguililla, where El Mencho was born, is at the center of the battle, and pride is therefore at play. Violence grew in Aguililla after the CJNG attempted to drive out local rivals including Cárteles Unidos, an alliance of cartels that include the Viagras and Cartel de Tepalcatepec.

“El Mencho is at war in Michoacán for several reasons. One is that, the Port of Lázaro Cárdenas, one of Mexico’s largest seaports, is located there, and controlling the state also gives access to a rail system. But most importantly it’s his home state: he takes it as a personal affront that other cartels are trying to take control,” said Vigil.

In the east of the state, the CJNG has also been hit hard.

On March 27, the Correa, a family-run cell with links to the once-powerful cartel, La Familia Michoácana, carried out an assault against a crowd at an illegal cockfight in the town of Zinapécuaro. The target was William Rivera, alias “El Barbas,” a local CJNG leader. El Barbas was one of the 20 people killed in the attack.

SEE ALSO: David vs. Goliath – The Family Clan Defying CJNG in Michoacán, Mexico

The Correa, headed by Daniel Correa Velázquez, alias “El Tigre,” began their criminal life in illegal logging, The Yucatan Times reported. Now, however, it has moved into drug trafficking, and does not fear quarrelling with the Jalisco Cartel on El Mencho’s native land.

Another notable action in the area’s turf war was the arrest of Juan Miguel N., alias “El Johnny,” a leader of the Rojos, a small group with strong links to the state of Guerrero, another drug trafficking hub on Michoacán’s southern border. The Rojos have previously fought against the CJNG in both Guerrero and Morelos, and the arrest of El Johnny suggests the group may be looking to expand in El Mencho’s home state.

But Michoacán isn’t the only place where the CJNG has seen its efforts to gain control fall short. In Guanajuato, the gang has been fighting with the Santa Rosa de Lima since 2017. In Veracruz it is embroiled in a war with the Old School Zetas.

Where the cartel was once seen as an incredible threat, recent instability and questions over the whereabouts of its leader, may give local groups the incentive to stand firm.

“The CJNG grew very rapidly — it’s probably the fastest growing cartel in the history of Mexico. But they have been unable to solidify all territory they have gained, and this leads to insurrections,” Vigil said.