In the northwest corner of Guatemala, a little known criminal organization known as the “Huistas” dominates the underworld, in large part due its ties with businessmen, law enforcement officials and politicians.

Introduction – Three Massacres in Huehuetenango

On the horse racing track known as “Carriles la Frontera” in the Aldea Agua Zarca, a border zone in the department of Huehuetenango, a competition was taking place between Guatemalan and Mexican horse breeders. Despite being a remote area, this was not an unusual event. It was even announced days earlier by the radio station K-Buena.

Among those in attendance were Darío Molina, Walter Montejo and Aler Samayoa, three recognized leaders of the “Huistas,” a drug trafficking group associated with Mexico’s Sinaloa Cartel. None of them had an arrest warrant or an extradition request from Guatemalan or US authorities. Their presence at the track was shared by a security ring that comprised of three levels of protection around Samayoa and a vast monitoring apparatus that extended to the Pan-American Highway, approximately 20 kilometers away.

This is one part of a multipart series concerning elites and organized crime. Read the full Guatemala report here, or read the other parts of this investigation here.

The security ring in Cuatro Caminos, a town within the neighboring municipality of La Democracia, raised the alarm when it detected the presence of a caravan of vehicles that were transporting more than a dozen suspected “narcosicarios” (“narco-hitmen”) that were planning on assassinating Samayoa so that the Mexican criminal group the Zetas could take control of Huehuetenango.

The Huistas’ security apparatus worked. It not only prevented the assassination of their leaders, it also neutralized the attackers. Seventeen people were killed in the clash between the two groups, although there is speculation there were additional deaths on the Mexican side. With this battle, the Huistas consolidated their power, which coincided with the decline of a rival local group associated with the Gulf Cartel.

****

Huehuetenango, December 2012. A vehicle carrying a businessman and some government officials was ambushed on the night of December 23. The crime scene was dramatic: the authorities found the bullet-riddled bodies of the victims in two burned cars (pictured), with 200 shell casings littering the ground nearby.1 The dead included Luis Antonio Palacios, a local businessman and manager of a luxurious hotel, as well as an official with the Attorney General’s Office, a high-level official working on the first lady’s social programs, and four other individuals.

Palacios had two partners in the hotel, one of whom also worked with him in a coffee export business, according to the Guatemalan newspaper elPeriódico.2 The hotel, La Ceiba, has two pools, a disco and a Jacuzzi. It conducted business as usual despite the attack on Palacios. The hotel’s Facebook page had advertisements announcing a New Year’s celebration and other activities through Valentine’s Day.

According to Prensa Libre, the authorities linked Palacios to drug trafficking groups in the area and said that one of the burned vehicles had a hidden compartment.3 However, neither drugs nor money were found in the car. And there has been no investigation into Palacios’ activities even though official sources told InSight Crime that he was laundering money for Aler Samayoa, alias “Chicharra,” the leader of the Huistas.

To be sure, Palacios’ death appears to be connected to an internal dispute, according to local sources consulted during this investigation. Apparently the hotel and other businesses are money laundering fronts for the Huistas, according to sources that did not want to be identified for fear of reprisal. It is not clear if the officials that traveled with Palacios had links to organized crime, or were simply in the wrong place at the wrong time.

****

Six months later, on the night of June 13, 2013, a similar attack took place in a municipal building in Salcajá, Quetzaltenango. A caravan of vehicles stopped in front of the National Civil Police (Policía Nacional Civil – PNC) station, where a dozen armed men entered and assassinated eight police agents (pictured) and kidnapped a police official.

During its coverage of the attack, Radio Sonora, an important national radio station in the country, invited its listeners to report the caravan’s movements. Between 8:00 p.m. and 11:00 p.m. they received calls; some were transmitted on air in which the callers said the caravan was on the road connecting the municipality of Huehuetenango with Mesilla, a small village on the border with La Democracia. The callers pointed out that the PNC and the army were not taking action against those responsible, laying bare on live radio the links between the authorities and the drug trafficking groups operating in the area.

The kidnapped police officer’s body surfaced the following week, and the investigation found Eduardo Villatoro Cano had ordered the officers’ assassination as a reprisal for a “tumbe” (drug robbery). At that time, Villatoro Cano was an enemy of the Huistas.

Once this was confirmed, the PNC and the Attorney General’s Office (Ministerio Público – MP), with the help of the army, launched an operation involving up to 2,000 officers designed to dismantle the group. They captured more than a dozen people, seized vehicles, weapons and drugs, and finally managed to have Villatoro Cano arrested in Mexico.

This operation weakened the Huistas’ rival group, almost to the point of extinction. It also demonstrated that the state security forces could, if given the task, dismantle criminal groups by using intelligence and police action. Following Villatoro Cano’s capture, the question became: Why did the security forces respond quickly and effectively to Villatoro Cano, but there had been no concrete actions taken against the Huistas?

This investigation explores the possible answers to this and other questions about the Huistas by investigating the relationships between politics, elites and organized crime in the department of Huehuetenango, Guatemala.

This is our attempt to make public these links, but it should be noted that this is difficult territory to investigate. Huehuetenango and its surroundings are in large part a black hole with respect to the news and official information. The nucleus of the Huistas is still active and maintains influence over state authorities and non-state actors. And the majority of the sources for this report preferred to talk on condition of anonymity out of fear of reprisal.

Context – Huehuetenango: Between the Communal and the Global

Huehuetenango is a key region for understanding the multiple dimensions of the relationships between organized crime, elites and local power groups, communities and the state. It is a department in northwest Guatemala, on the border with Mexico. It sits adjacent to the departments of San Marcos, Quiché and Totonicapán.

It is a territory profoundly integrated into global dynamics for at least three reasons: it is a border territory, it constitutes a throughway for goods and people, and a lot of international migration emanates from the area.

Since the colonial period, Huehuetenango has been a region on the periphery with respect to the Guatemala valley, and as a result, with respect to the political and economic dynamics formed there. At the same time, it is an area characterized by its commercial and cultural fluidity and by its links to Mexico. Its location on the margins of central Guatemala contributed to the consolidation of community identities and the development of a certain degree of local autonomy.

In addition, the department has historically been a throughway for people and goods; the archaeological and ethnohistoric evidence shows the presence of objects in Huehuetenango that came from various parts of Mesoamerica. What is today considered to be contraband has long been a form of work in the area, which is probably a fact that has facilitated the operations of today’s drug traffickers. It is not a surprise, then, that at the end of the 1970s, the residents of various municipalities in Huehuetenango began to migrate to the United States. Initially this involved the movement of individuals, but later networks were established that facilitated the transit and placement of the so-called “Huehuetecos” in the US.4

While the criminal groups studied in this investigation have links to transnational groups, they are profoundly local and have developed a kind of symbiosis with the political, social and cultural environment that is shaped in some form by the shared history of the region, including the transit of goods and, later, people. The links between the criminal groups and political elites in this region also reinforce the the existence of “Illicit Political Economic Networks” (Redes político-económicas ilícitas – RPEI), a term invented by the International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (Comisión Internacional Contra la Impunidad en Guatemala – CICIG) to explain this phenomenon.5 The RPEI maintain control over key political positions — town councils, city halls, provincial governments — that have been used for personal enrichment, as well as the construction and consolidation of social bases. Some of the RPEI’s activities are developed on the margins of the law, which is why it is difficult to establish a clear distinction between what is licit and what is illicit.

Huehuetenango’s peripheral nature has also contributed to unique development dynamics. The geography has created differences between distinct regions and in some cases even within municipalities. Some 79 percent of the population lives in rural areas; in some municipalities, this figure reaches over 90 percent. This implies not only the dispersion of the population in small towns but also the development of a degree of autonomy. According to 2014 statistics, 73.8 percent of the population lives in poverty and 28.6 percent in extreme poverty. Fifty-six percent of the population is indigenous, and in 18 of 32 municipalities this figure surpasses 90 percent.6 More than a quarter — 28.1 percent — of the population is illiterate.

The geography, the ethnic diversity, the dispersion of the population and the lack of infrastructure enabled the construction of micro-regions in the interior of the department that generally have a weak state presence, which permitted the creation of unique sociopolitical dynamics.

This geographical diversity has created in Huehuetenango a “complex network of villages” that connect these towns to each other and to Chiapas, Mexico, which has enabled cross border commerce that has somewhat reduced the complete dependence on agriculture. In the department, there is a very intense relationship between the identities of the towns and their geography. The history and geography have contributed to the development of a distinct sociopolitical and cultural framework.7 The community panorama of Huehuetenango has territories controlled by specific indigenous groups, areas where multiple indigenous groups are present, and territories occupied by Spanish-speaking indigenous, known as “ladinos.”8

With the expansion of coffee crops, since 1860, the towns with fertile soil for coffee-growing were affected by the expropriation of the land and subjugation of the work force. The owners of coffee plantations became local elites that controlled the political power, the economy, and the labor market. They are, in effect, the principal economic elites in the area. Since colonial times, their distinct forms of social control and labor exploitation led to diverse strategies of community resistance. In addition to armed insurgency and political uprisings, families and communities migrated to the mountain and jungle areas in order to escape from forced labor.9 With the introduction of the coffee crops, Huehuetenango also became linked to the globalized economy, although the organizational structure of means of production and the society were not necessarily capitalist.

The economic, social and political changes triggered by the October Revolution of 1944 (as it is known in Guatemala) continued despite the US intervention in 1954 that toppled president Jacobo Árbenz (for more on this, see introduction). The communities that maintained a certain degree of isolation and relative autonomy became increasingly linked to the internal market and the national political scene. Economically, the end of forced labor and the period of growth that followed World War II resulted in social differentiation and economic accumulation. In several of the border municipalities of Huehuetenango, for example, the small-scale contraband of Mexican products became not only a subsistence strategy, but also a mechanism of accumulation that would form the economic base of some of the emerging elites in the years to come.

Nonetheless, the processes of social differentiation, the dispute for local power and the confrontation over control of the land became integrated with the insurgent movement at the end of the 1970s. During the civil war, especially between 1979 and 1984, the department’s internal power structure was modified.10 A good portion of the elite ladinos in the indigenous communities migrated to Guatemala City and the department capital, Huehuetenango, and the power of the coffee landowners began to fade.

The changes that began in the second half of the 20th century, particularly during the October Revolution and the civil war (1960-1996), resulted in these groups losing power and the disappearance of the majority of the large plantations. They gave way to small and medium-sized properties that are now the principal coffee producers in the department. Currently, the businesses interested in exploiting water and mining resources, which are mostly multinationals, have made alliances with national and local groups to implement their projects, although they face strong community opposition.

In sum, the power groups — the predominant farmers and the traditional ladinos — were displaced by the effects of the civil war, since many ladinos opted to migrate to the departmental capital or to Guatemala City, and the municipal power changed hands.11 These changes provoked, initially, a sort of power vacuum, which was occupied by diverse groups.

This vacuum at first was filled by the army and its paramilitary arm, the Civil Defense Patrols (Patrullas de Autodefensa Civil – PAC).12 For a large part of the 1980s, the head of the military in the area assumed the coordination of the public entities in the department, and maintained control over the municipalities and the communities via the PAC. This situation began to change when the country returned to a democracy in the mid-1980s; the demilitarization of the government continued through the peace process of the mid-1990s.

Since the beginning of this century, the local and departmental power structures have become more complex, fluid and decentralized. The municipal autonomy and the decentralization of functions and resources have enabled both city halls and the very communities to exercise control over certain local decisions. For their part, the regional power groups have achieved a certain influence in the department and have constructed national alliances. Within this context, criminal groups have developed and established themselves in some areas of the department.

Huehuetenango’s political elites have been formed within this regional context and in interaction with a national political system characterized by the fluidity of its political parties. These parties are based on individuals rather than political ideology, and the private financing of electoral campaigns. This political system not only has democratic deficits, it has made politics as a whole a form of personal enrichment, in which elections permit the people and groups involved to access key positions for their own benefit. At the same time, politics has been penetrated by private interests that prevail over those of the general public.13 These actors that look to influence the political decision-making process range from large multinational corporations and businesses to criminal groups.14

In Huehuetenango it’s possible to identify various Illicit Political Economic Networks (RPEI) by studying what Jahir Dabroy called the political lineages of the department.15 These are family clans that have achieved control over city halls and district councils, where they consolidate their political and territorial bases and remain entrenched in public office.

One example is the López Villatoro family. Originally from the municipality of Cuilco, the family owns a diverse array of businesses. The López Villatoro family has constructed a political network in the southern municipalities of Huehuetenango that allows them to exert decisive influence in elections.16

One family member, Roberto López Villatoro, known as the “Tennis Shoe King,” is accused of conducting smuggling operations.17 He is also thought to have influence within the judicial system. And while he has been accused of criminal activity in the past, none of the allegations against him have led to a successful criminal prosecution.18

The Huistas, Their Illicit Activities and Their Protection Network

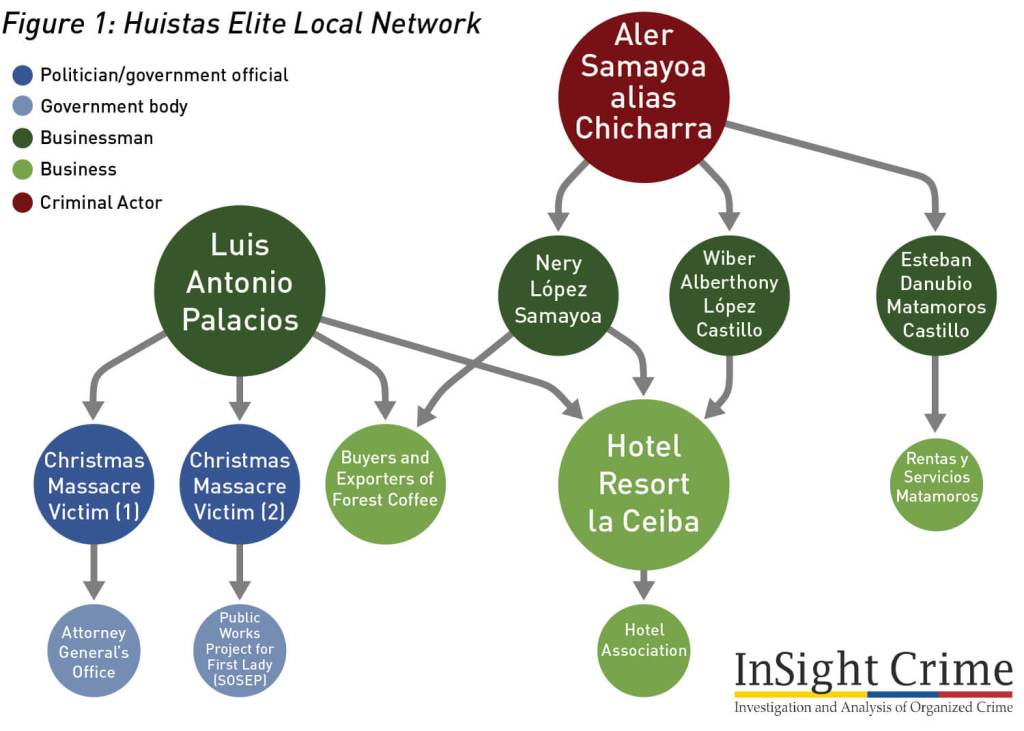

The diverse and extensive geography, as well as the border location and the constant flow of people and goods, create opportunities for an array of criminal groups to operate. As previously mentioned, the group led by Aler Samayoa Recinos (pictured), alias “Chicharra,” based in the Huista region, is one of the groups operating in Huehuetenango with the most autonomy and organizational development. The centralized and hierarchical organization includes structures specialized in money laundering as well as smuggling, storing and producing drugs.19

According to local and national sources, as well as prominent politicians in the area who prefer anonymity, the basis of the Huistas’ illicit activity was established years ago. Since the 1970s, marijuana and poppy have been planted in some of the mountainous areas of the department, but these were isolated activities that responded to the demand of Mexican intermediaries. It wasn’t until the end of the 20th century that groups like the Huistas developed the capacity to handle the storage and transport of drugs into Mexican territory. Initially, these groups were comprised of Mexicans who belonged to the Sinaloa and Gulf cartels that had established alliances with local groups and who also had experience with contraband and migrant smuggling. These groups gradually built their own logistics structures, which permitted them to move and store drugs from the capital city, Huehuetenango, all the way to the border.

The Huistas took their name from the area where the group is based. “Huista” refers to San Antonio Huista and Santa Ana Huista, two small municipalities in the department’s northeast. The group is linked to the Sinaloa Cartel, but little by little it has acquired a certain degree of autonomy. It has gone from transshipment to storage and, in the last five years, to the production of methamphetamine. The Huistas also developed a national strategy, which in addition to providing the group with an infrastructure for drug trafficking, has enabled it to build a network of businesses that include: hotels, recreation centers, businesses, workshops, construction companies, and even computer academies, according to official sources that have investigated the group. All of these businesses have allowed the group to not only launder illicit money, but also to establish contacts and links with business people, officials and other authorities through intermediaries on the local and national level.

With the intensification of the government’s efforts to fight drug trafficking, the conflicts between Mexican cartels and the rise of networks dedicated to “tumbe,” or drug theft, security is fundamental to the survival of these criminal groups. The Huistas, for example, have created a sophisticated security apparatus that is designed to protect Samayoa and the group’s principal leaders from attacks by rival groups and potential security operations designed to capture him. It is also intended to protect the group’s licit and illicit activities, and establish a safety zone in its territory.

This security system monitors the principal roads, bridges and intersections and controls the passage of people and vehicles. It also reports any suspicious movements. Once the alarm is raised, the members of the apparatus analyze the potential threat. Generally, each “lookout” is comprised of two people: one is on foot and responsible for the communication, and the other is on a motorcycle, ready to follow any suspects. The investigator of this report observed how these lookouts operated, and on occasion was photographed by them.

This monitoring system is fundamental for the group to maintain territorial security, however it is insufficient to shield them from operations by the security forces. That is why in addition to maintaining territorial monitoring, the group has created a network of informants within the PNC and the Attorney General’s Office at the local level. According to one source,20 the group maintains relationships with commissioners, deputy commissioners and police in Huehuetenango and the neighboring department of San Marcos, some of whom are on the group’s payroll, and provide them with information on both police operations and the activities of rival groups.

The network extends to the judicial system as well. In the local Attorney General’s Office there is apparently a flow of information from relatives who work there, as well as corrupt officials, who provide the group with information on inquiries or investigations against them. At the highest levels, there are allegedly contacts in both the legislative and executive branches, which will be explored in the following section.

The effectiveness of this security system became evident when the group of hit men linked to the Zetas tried to ambush the Huistas during the horse race in November 2008. At that time the Zetas were the most feared criminal group in Guatemala. Its strategy was to control territory in order to charge “piso,” or rent, on all of the illicit and many of licit activities in the area. That strategy aligned perfectly with its distinctive character and military origin: the group’s nucleus had defected from Mexico’s Special Forces. The Zetas also looked for local allies that had the same distinctive character. That’s how they found Eduardo Villatoro Cano, who employed equally rough and violent tactics.

In March 2008, the Zetas killed Juancho León, the most powerful person in Guatemala’s underworld at the time. With the help of their allies, the Zetas were taking control of eastern Guatemala and its drug corridors. By November 2008, they were already eyeing the western half, specifically Huehuetenango. Nonetheless, instead of eliminating their enemies, it was the Huistas who ended up leaving over a dozen Zetas operators dead.21 As noted, the massacre consolidated the Huistas’ power in the area and provoked the decline of Villatoro Cano’s group.

The Huistas and Social Control

Within its territory, principally in the municipalities of Santa Ana Huista and San Antonio Huista, the group’s security strategy focuses on the construction of a protection network and an unwritten rule that punishes informants; and the construction of social legitimacy based on the sharing of wealth. The money laundering activities have enabled the creation of a network of businesses that offer employment to the residents of the municipalities. Participation in the group’s various illegal activities has become a sign of prestige and a source of aspiration for a large number of youths in the municipalities, who hope to become part of the group. (These same youths form part of the aforementioned security networks.)

On the other hand, the inhabitants of these municipalities know that any comment that reveals the group’s activities is violently punished. In everyday conversation there is an agreement to not talk about “that.” Everyone knows, but no one mentions it, and when locals talk with visitors or foreigners, these topics are not discussed. In addition, in the towns there is a “zero tolerance” policy towards common crime. The Huistas’ security groups have assassinated suspected gang members, rapists and criminals in order to prevent the presence of rival groups and demonstrate to the communities that their presence guarantees them safety.

The National Civil Police rarely intervenes in these types of situations. In fact, it is common knowledge that some of its members are on the group’s payroll. Although there is a strong police presence on the roads leading to the municipalities of San Antonio Huista and Santa Ana Huista, the security agents do not stop the transporters believed to be smuggling illicit substances. Indeed, they appear to protect these groups, as they exert a strong control over the visitors and strangers who visit the municipalities.

According to information collected in the field that was informally confirmed by officials within the Attorney General’s Office and the General Directorate of Criminal Investigation (Dirección General de Investigación Criminal – DIGICI), the Huistas have diversified their drug trafficking activities to include the production of methamphetamine in their areas of control. Nonetheless, their principal revenue stream continues to be the smuggling of cocaine from the Honduras and El Salvador borders, as well as from the Pacific coast and Guatemala City, to the Mexican border. The Huistas have storage facilities in Huehuetenango, Santa Ana Huista, San Pedro Necta and Nentón.

According to former prosecutors from the Attorney General’s Office that investigated drug trafficking activity in Huehuetenango, every week there are drugs being shipped from the eastern border, southern coast or Guatemala City into Huehuetenango. Caravans of three to five vehicles carry the drugs in hidden compartments inside the cars. During these transfers, the security system is in place in order to anticipate checkpoints, police operations and the presence of rival groups.

The group has also been detected using small trucks that are supposedly empty but in reality have hidden compartments. These caravans do not stop at checkpoints set up by police or MOSCAMED, the agency in charge of eradicating the Mediterranean fruit fly, according to the aforementioned sources. An official in the Guatemalan army who asked for anonymity said there is a de facto agreement between the criminal groups and local police authorities that permits the drug smuggling operations.

The drug trafficking routes that begin in Guatemala City pass through Chimaltenango, Los Encuentros, Cuatro Caminos, Huehuetenango and the Gracias a Dios border. An alternate route links Cuatro Caminos to Quiché, and from there heads towards the border. From the southern coast, the route passes through Zarco, Quetzaltenango, Huehuetenango and the border zone. Another possible route goes through Alta Verapaz, Baja Verapaz, Uspantán, Cunén, Zacapulas, Aguacatán and Huehuetenango before finally arriving at the border.22 All of these routes pass through La Democracia, Santa Ana Husita and Nentón, which confirms the existence of drug storage facilities in these municipalities.

In addition to the use of land routes from one border to the next, sections of roads in northern Huehuetenango have been identified as runways for drug planes. On the outskirts of Nentón, there is a formal runway that is sporadically used. According to local informants, the operations are conducted in a matter of minutes; the section of the road is illuminated by torches, where the plane lands before the drugs are unloaded into four or five pickup trucks. Once this is done, the plane takes off, and the vehicles bring their load to the established warehouses. In addition, methamphetamine laboratories have been detected in the municipalities of La Democracia, Santa Ana Huista, Jacaltenango and Nentón, which, according to officials from the Attorney General’s Office and DIGICI, means the storers and transporters are now becoming producers.

The Huistas and the Local Economic Elite

The Huistas’ money laundering structure has resulted in the formation of a network of businesses that extends into various departments of the country, but the nucleus is in Huehuetenango. In this department, the group has been known to make investments in real estate, hotels, recreation centers and possibly the cultivation and sale of coffee, according to sources in the Attorney General’s Office that have investigated the case. These businesses include: the Hotel & Resort La Ceiba on the Inter-American Highway; the housing complex Mira al Bosque in Huehuetenango City; the recreation center and shopping mall Victoria Center in Santa Ana Huista; the Finca el Sabino in La Democracia; and other properties in the departments of Retalhuleu, Izabal and Petén.23

The manager of Hotel & Resort La Ceiba was Luis Antonio Palacios, who died in the 2012 Christmas massacre along with six other people. According to the trade register consulted at that time by elPeriódico, the hotel was registered under the names of Nery López Samayoa (pictured) and Wilber Alberthony López Castillo.24 According to official sources consulted for this investigation, López is a very important part of the Aler Samayoa network, appearing as the owner of several properties and businesses belonging to the Huistas. He was also a partner of Palacios in a business called Compradores y Exportadores de Café del Bosque (Buyers and Exporters of Coffee of the Forest), according to the trade registry consulted by elPeriódico.25

The contact between the Huistas and Compradores y Exportadores shows the interest and possible activity of the group in the most important agricultural sector in the region. To be a producer and exporter of coffee would not be outside the norm for an organized crime group. From Honduras to Colombia, the agriculture industry and livestock are the best ways to camouflage large capital flows and the movement of illicit products. It also serves as a way to accumulate political and social capital.

In the case of the Huistas, it may have even more significance. The flight of the large coffee growers in the last 30 years has left a power vacuum of elites in Huehuetenango. On the one hand, it could be argued that the politicians and emerging businessmen are filling that vacuum, something which we will cover in the next section. Nonetheless, groups that are accumulating capital via illicit means — whether it be contraband or drug trafficking — also appear to be well-positioned to fill the power void.

The Huistas appear to be part of the other large industry associated with the emerging business class: the hotel sector and shopping malls. Both businesses represent areas where it’s possible to invest large sums of money without much oversight — even in foreign currencies — as well as the expansion of social and political networks. For example, Hotel & Resort say in their advertisements that staying in the hotel costs roughly $200, however the real price is closer to $30, which presents ample possibility to manipulate the accounting books.26

The hotels and shopping malls also appear to be places where it’s possible to establish networks with authorities, security forces and potential partners. Several official sources commented that the hotels are where the parties (with an abundance of alcohol and prostitutes) take place in order to earn the trust of members of the Attorney General’s Office, the police and the army. “They don’t even have to be bribed” with cash, one official said.27

The supposed link between Palacios and the Huistas also provides us a clue about how the managers of this important business intersect with certain bureaucratic elites.28 At least two of those who were with Palacios on the night of December 23, 2012, were prominent members of the government: one was the prosecutor of the Attorney General’s Office and the other was the director of the Secretariat of Social Works of the Wife of the President (Secretaría de Obras Sociales de la Esposa del Presidente – SOSEP) in the department of El Progreso.

Lastly, the hotels and the shopping malls give a certain social cache to their owners because they represent some of the few public spaces in these areas, spaces that end up determining the social activities of the locals. The Hotel & Resort La Ceiba, for example, opens its pool to the public on the weekends for a minimal fee.

The Huistas understand the importance of building social ties and therefore maintain very close contact with an individual associated with the local soccer team. As we have seen in the other case study, the local soccer team not only represents a common space where fans get together, but also a place to build one’s networks.29 That same contact on the soccer team, for example, is also a frontman for one of the Huistas’ businesses and was even a mayoral candidate.

The Huistas and the Political Elite

The strongest relationship between the Huistas and the elites appears to be through the local politicians. According to three politicians in Huehuetenango, those who exercise a substantial amount of power in the Huistas’ area of influence are members of this group, which is why during electoral campaigns they obey the tacit pact of silence regarding the group. Generally, the mayoral candidates seek to avoid direct and public contact with these groups, although the distance is observed in such a way as to avoid conflict with them. As previously noted, the security role these groups assume ends up being useful to the local authorities, who have one less problem to face.

Several local sources say that, in certain situations, the Huistas finance some municipal activities such as festivals, although on occasion they have helped with payroll, and some infrastructure projects. Nonetheless, this relationship has become tense at times. In 2010, to cite just one example, the mayor of La Democracia was assassinated. According to one source,30 the mayor was killed because he began to use the town’s ambulance to transport drugs from Guatemala City to Huehuetenango, and eventually tried to act autonomously.31

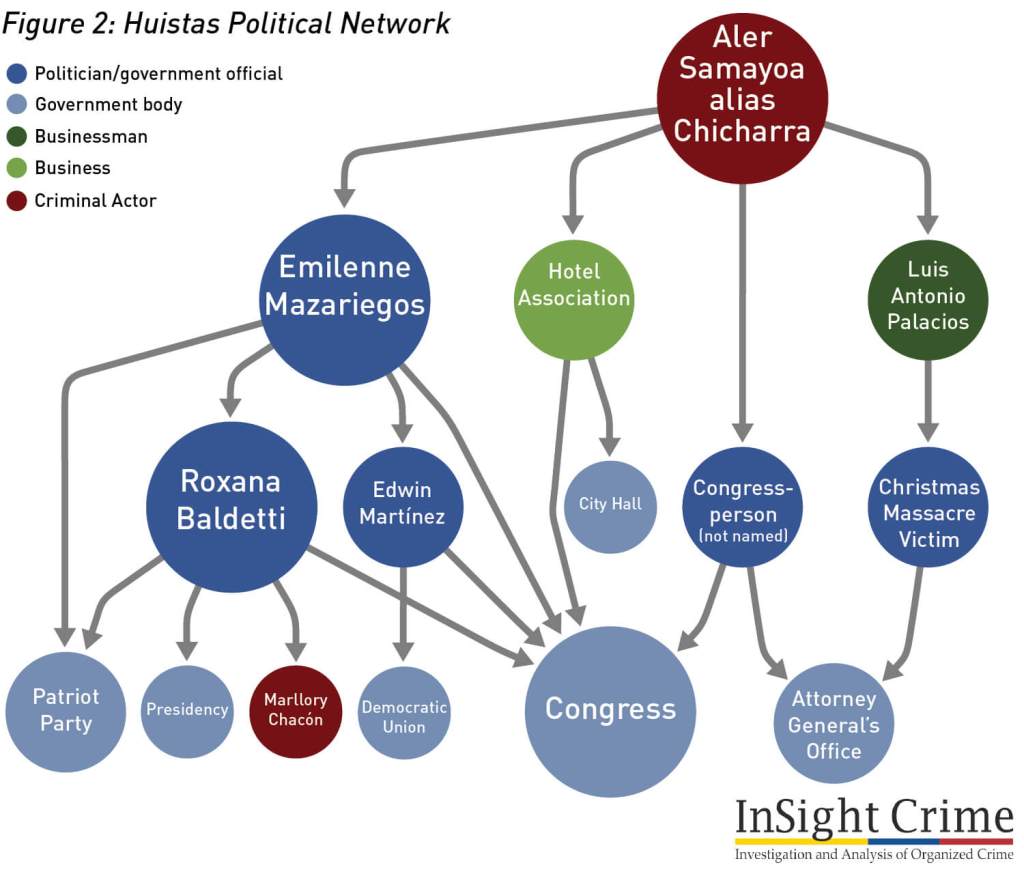

At the departmental level, these groups’ key relationships, according to several sources, are with: the district representatives, the local Attorney General’s Office and the hotel association. In addition to information provided by both city and departmental sources, elPeriódico has published several articles on the existence of links between the Huistas and the representative Emilenne Mazariegos, as well as another individual that has worked both in the Attorney General’s Office and as a congressional representative. These connections could also serve as interlocutors to manage contacts at the highest levels of government.

The district of Huehuetenango32 happens to be an electoral priority for all parties, because of the number of voters, the quantity of representatives that are elected from the department, and the number of mayors it has. It is the district with the third-highest number of voters, behind the municipalities of Guatemala and its surroundings.33 However, political parties are not well organized in Huehuetenango,34 since the parties prefer not to legally organize themselves in order for the central authorities to be able to name mayoral and representative candidates.

This district elects 10 of the country’s 158 congressional representatives.35 Representatives constitute key pieces in the creation of the distinct levels of political action because they are integrated into national networks through legislative blocs. They also have influence over the decisions that affect their department, which enables some of them to be the natural interlocutors with the voters. Moreover, they generally have projects in the municipalities and communities. They play an important role because they are the players that act with the most autonomy in the different spheres of political action, which allows them to help both their constituents and financiers.

At the national level, they can negotiate and influence global public investments, the location of certain projects, funds for the departments’ development councils, etc. In the departmental arena, congressmen influence the composition and functioning of the local bureaucracy, particularly in areas such as health and education, where they insert members of their networks as public employees. In the municipalities, they establish relationships of reciprocity with local and community groups. In sum, influence over congressional representatives equals a large supply of political, social and economic capital.

The development of the congressional representatives as the nucleus of the departmental power groups is relatively recent. One of the results of democratization was the weakening of the centralist government and the erosion of the power of the presidency. This was complemented by the laws of decentralization and the strengthening of the development councils, which awarded the departments with more resources, and a certain degree of autonomy to determine their own destiny. This contributed to the empowerment of some local actors that, through their control over public works (managed by private businesses and independent brokers known in Guatemala as non-governmental organizations, or NGOs) and the departmental bureaucracy, managed to consolidate power structures. This in turn increased their capacity for influence at the national level and, in many cases, improved their prospects for illicit enrichment.

The now former Congresswoman Emilenne Mazariegos (pictured) is a good example of this dynamic between the central powers and local politics. She was not born in Huehuetenango, but she penetrated the department’s political life through her association with the representative Edwin Martínez of the Democratic Union (Unión Democrática – UD), a party she joined in 2003. In 2007, she ran in the number two position in Huehuetenango, making a pact with Martínez — who she had or had not married, depending on the source36 — that if the party did not win the necessary number of votes to elect two representatives, they split time in congress. At first Martínez complied with the pact, and after two years he asked Congress permission to hand over his responsibilities to Mazariegos.37 Nonetheless, 11 months later, Martínez returned to Congress to replace her. There was a public dispute, and Mazariegos was forced to cede the office.

Mazariegos would later return to Congress, but this time with the Patriotic Party (Partido Patriota – PP). During her time in Congress, Mazariegos established a close relationship with the secretary of the PP and eventual vice president of the country, Roxana Baldetti.

Baldetti is a controversial figure in Guatemala. The former beauty queen and owner of beauty salons is a good representation of the new political elite in Guatemala. After serving on the public relations team for the presidency at the beginning of the 1990s, Baldetti became a candidate and later a congressional representative. Through politics, she would consolidate her own private economic empire. During her time as vice president (2012-2015) she was repeatedly accused of corruption. She was also believed to have been associated with the money laundering structure run by Marllory Chacón, the so-called “Queen of the South,” who was sentenced in the United States on drug trafficking charges.38

In April 2015, the CICIG and the Attorney General’s Office said Baldetti was part of the criminal structure that defrauded the customs office.39 Baldetti resigned and she is currently in prison while her trial proceeds. This was the beginning of a series of corruption cases against representatives, mayors and the highest levels of the executive branch including the president himself.

The political elite was formed though its control over public resources, which were used to enrich themselves and remain in positions of power. One of the key institutions for understanding this corruption dynamic are the development councils. These kinds of councils are where power is built in Guatemala today. The 1985 Constitution established that the municipalities would receive 8 percent of the national budget (distributed according to the size of the population); this number was raised to 10 percent following the peace agreement.40 On top of this was the “executable” revenue for the departments that went to public works projects and the operating costs of the departmental bureaucracy.41

The government, which was further weakened by a series of neoliberal reform measures in the 1990s, stipulated that public works had to be carried out by private businesses. The government did not create a strong regulatory framework, however, and these businesses now compete for public funds without proper oversight. In addition, the decision of the state to provide certain services through the aforementioned brokers, the NGOs, entities that receive public resources, has further weakened the government’s hold over the process.

This resulted in the proliferation of construction companies and NGOs42 that became intermediaries in the implementation of public works projects. Generally, these businesses or NGOs operate under the control, or in the orbit, of these elites who, in exchange for public works concessions, receive commissions and in some cases are part of these economic structures.

This system has turned the public budget into a battleground between political groups, construction companies and other state providers.43 The fragmentation and fluidity of the party system has resulted in such a situation that when the executive lacks a parliamentary majority, it exchanges votes for resources destined for public works, which are channeled to businesses in which the representatives have stakes or which finance their political campaigns.

Political actors are not the only participants in the dispute for public works projects. In a systematic manner similar to what has been seen in other countries in Latin America, drug trafficking groups have built construction firms that permit them to access public funds while also laundering their money and diversifying their business portfolio. Guatemala is no exception, as illustrated with the country’s most notable family-run drug trafficking groups. To cite just two examples, in the northeast, the Mendoza group has builders that have won public work assignments; and in Alta Verapaz, various businesses owned by Ottoniel Túrcios — who until relatively recently was incarcerated in the United States — benefitted from government contracts during the management of Obdulio Solórzano — who was linked to drug trafficking and murder — and the presidency of Álvaro Colom (2008 – 2012).

The Huistas are no exception. This investigation found that at least one construction firm was linked to this group. The company is called Rentas y Servicios Matamoros, which is registered under the name of Esteban Danubio Matamoros Castillo. This business benefitted from municipal projects44 in Huehuetenango between 2012 and 2016, according to the website Guatecompras.45 According to the CICIG, Danubio Matamoros is an alleged drug trafficker, and authorities have issued a warrant for his arrest. He is currently a fugitive from justice.46

The Huistas’ links with the political elite are not limited to the municipal level; they also have relationships with representatives and officials within the executive branch. Several local sources have said that the group financially backed Emilenne Mazariegos’ congressional campaign in 2011.47

Mazariegos denies any type of link to the Huistas, and there are no formal accusations against her. Nonetheless, according to a civil society leader in Huehuetenango who requested anonymity for security reasons, Mazariegos admitted that she had 4 million quetzales (roughly $500,000) to finance her 2011 campaign, a large sum for a local election. When she was interrogated by a journalist about the origins of this money, she hesitated before saying that it came from her businesses, without providing further details.48 She later used a much lower figure, saying that her campaign had 800,000 quetzales (close to $100,000).49 Mazariegos was re-elected as a representative of Huehuetenango in the 2015 elections, but the Supreme Electoral Tribunal declared her “unsuitable” due to alleged “influence peddling” with employees of a state health care agency.50

We should emphasize that the two people accusing Mazariegos of having a connection to the Huistas are political rivals, as well as a source that works with the government intelligence services and another source connected to a local think tank. Mazariegos has not just denied the accusations but, on at least one occasion, has threatened to sue a journalist from Plaza Pública who asked about these alleged connections.

“How can you say that?” she reportedly asked the journalist. “I am going to sue you for defamation.”

InSight Crime called two telephone numbers it had for Mazariegos, leaving detailed messages on both, and we sent an email asking for her response to these matters. However, Mazariegos did not respond to our efforts.

The case involving the other representative linked to the Huistas is different. Because there is less certainty and few sources on this person, InSight Crime is not naming her. However, according to information collected by several sources on the ground, we can say that this person is from the region and therefore has contacts and relationships with these groups. Like in the case of Mazariegos, this person has been accused of receiving resources from these groups to finance congressional campaigns, although there are not any formal accusations against her.51

However, an ex-official from the Guatemalan government intelligence services said that the rise of this person to Congress was a “huge leap” for the organization in terms of their reach and power because “now they have a political operator on the inside … of Congress that is loyal and responds to the interests of the cartel.”52

In addition, former Attorney General’s Office officials say that she still maintains certain links with the prosecutor’s office as a result of working in Huehuetenango in that office. The weakness of the local Attorney General’s Office has forced the prosecutor’s office in Guatemala City to lead the investigations into organized crime in the region.

The Huistas and the Chamalé Group – a Comparison

In many ways, the Huistas are a typical regional organized crime group. They look for alliances that shield them from the law and from their enemies. They look to improve their businesses and launder money through investments in local businesses, especially those that deal mostly in cash and that can help them camouflage several activities at once. They intersect with elites — above all local political and economic elites — who can serve as interlocutors to political groups at the national level.

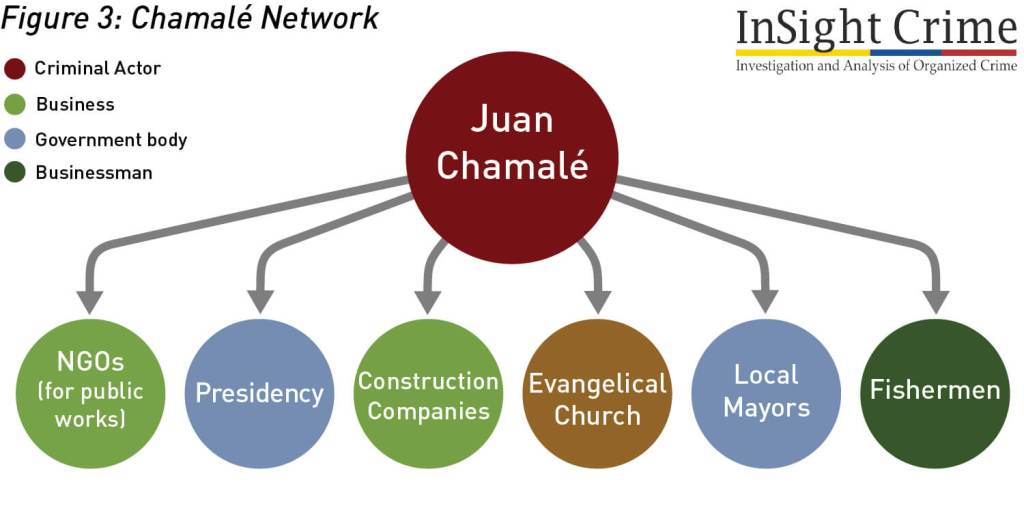

In this sense they are similar to another Guatemalan group that operates in the border area with Mexico. The Chamalé group is named after its leader, Juan Alberto Ortíz López, alias “Chamalé.” (pictured) Chamalé was a much more public figure than Samayoa, the head of the Huistas. He was a pastor and an open benefactor of political parties and candidates. He was the owner of businesses and NGOs that benefitted directly from the economic resources of the state. And he was openly violent within his area of operation in the south of San Marcos department, especially in the municipalities of Malacatán and Ayutla.

Both Chamalé and the Huistas also have been identified for having a strong relationship with the political parties in power. For his part, Chamalé allegedly provided funds to candidates of various parties at both the local and national level so that they would let him continue his illicit activities.53 He is also alleged to have had a relationship with Gloria Torres, sister of former first lady Sandra Torres. Chamalé allegedly negotiated municipal works projects with Gloria Torres,54 although Torres has never been prosecuted for these supposed ties.

This relationship was similar to the one the Huistas seek with representatives: fixers who provide access to both local and national power. This is fundamental for the Huistas’ business interests, especially in terms of security but also for money laundering purposes. It also provides a possibility for the group to accumulate political and social capital at the local level.

This type of political support comes from backing candidates with campaign funds. In Huehuetenango, all of the information linking organized crime to congressional representatives revolves around campaign financing and indirect communication with various officials. Nonetheless, as has been previously mentioned, concrete evidence does not exist. Based on the above information it can be inferred that the typical behavior of these groups is to build a circle of territorial protection through bribes and cooperation, and to establish agreements at the different levels of politics in order to achieve a certain degree of security for their operations and contributions to economic projects.

Nonetheless, in another sense the Huistas are distinct from the Chamalé group. For example, one of the peculiarities of the Huistas is their territorial nature. The Huistas region is defined by geography and a strong local ladino and indigenous identity. There is also a strong connection to the land as well as complex kinship and cronyism networks among the mestizos that favor the development of criminal structures.

This unique identity is explained, in part, by the demography and political importance of the region. While in the south of San Marcos — where Chamalé operated — there is an important state presence derived from the area’s strategic importance as an international commercial hub, the state has a weaker presence in the Huistas’ region. In the municipalities of Malacatán and Ayutla, where Chamalé operated, the respective city halls led development projects, and there was a strong culture of political activity.

In the aforementioned municipalities of Huehuetenango, community organizations look to meet the local needs and demands. While in the south of San Marcos, the indigenous population is a minority, in Huehuetenango, the Huistas municipalities (mainly mestizos) are surrounded by indigenous communities that have a strong identity and self-organization that contains the expansion and activities of the criminal groups. In short, the Chamalé group developed in a politically and economically strategic area, while the Huistas established themselves in a relatively marginalized area.

In addition, it appears the Huistas do not want to expand their territory nor fight over new drug routes. The large clashes this group has engaged in have been in defense of their territory rather than attempts at expansion, and although their leaders own properties in other departments, they and their families continue to live in Santa Ana Huista and San Antonio Huista as well as La Democracia. This has retained their status as a local group, which prioritizes the safety of their lives and operations, as well as the building of public works projects and the attainment of a certain degree of social legitimacy.

With respect to political links and legal protection, both groups managed to establish a strong influence over local authorities. This influence combines bribes to political and judicial authorities with distinct forms of interactions with local political leaders. Nonetheless, in Chamalé’s case, there was cooperation with the municipal authorities in Malacatán, especially regarding municipal infrastructure projects. In the Huistas area, there seems to be a coexistence based on tolerance rather than cooperation. What’s more, there is a strong element of family, or blood-relations, that control key positions and facilitate interactions among the various licit and illicit actors.

In both cases the groups established a degree of social legitimacy, but they did so using different methods. Chamalé began in the drug business through his experience as a fisherman. Gradually, he built a business emporium that included agriculture and ranching activities, cable television channels, construction companies and other legal activities that permitted him to build local and regional alliances. He also supported the churches in the area and considered himself to be an assistant pastor, which earned him social recognition. In a moderate and discreet way, Chamalé began to exhibit luxury goods and show them off at local festivals. In the end, he was considered an upstanding man, a benefactor and a legitimate businessman. Following his March 2011 capture, some workers on his farms protested, demanding his liberty.

Meanwhile, the Huistas and their leader, Aler Samayoa, have maintained a much lower and more localized public profile. The legitimate businesses they have founded are principally hotels and a recreation center. Although he’s well-known in the municipalities where he operates, since the incident with the Zetas, Samayoa almost never appears in public and, according to prosecutors, he has a sophisticated security system that has protected him from the authorities.

Perhaps what separates these groups the most are their respective uses of violence and how they maintain order in their areas of operation. According to the United Nations, the Chamalé group was responsible for approximately 50 homicides per year in Guatemala, and it is involved in extortion and land expropriation. The Huistas, according to what InSight Crime has been able to establish, are violent and take action against rivals and possible threats, but they do it outside of their territory in order to maintain relative calm and not expose themselves to criminal investigations. In addition, as was previously mentioned, the Huistas act against gang members, rapists and other criminals; indeed, their areas of operation are among the safest in the entire country.

Conclusion – The Huistas and Their Model of Resistance

It was the capture of Eduardo Villatoro Cano and the dismantling of his group, which had assassinated the police officers as reprisal for a “tumbe” (drug robbery)55 in 2013, which laid bare the differences between the Huistas and other criminal groups. The Huistas, it appeared, were relatively untouchable.

Indeed, in addition to the neutralization of Villatoro Cano, between 2010 and 2014 authorities captured the leaders of numerous Guatemalan drug trafficking groups. This includes the capture and extradition to the US of Mauro Salomón Ramírez (captured in October 2010) and Juan Chamalé (captured in March 2011), both of whom operated in the country’s southwest; Waldemar Lorenzana Lima (captured in April 2011) and Elio Lorenzana Cordón (captured in November 2011), from Zacapa in eastern Guatemala; Horst Walther Overdick Mejía (captured in April 2012), from Alta Verapaz; and Jairo Orellana Morales, a violent drug trafficker linked the Lorenzana group (captured in May 2014). As mentioned above, the Zetas group was also dismantled.

Despite the series of captures of important drug traffickers between 2010 and 2014 and the dismantling of the Villatoro Cano group, the Huistas and their leader Aler Samayoa “El Chicharra” remain intact. During the weeks-long investigation into the police massacre in Salcajá, the Villatoro Cano structure was linked to the Huistas, and numerous news articles noted the existence and regional importance of this group.56 Nonetheless, at the time of this writing the authorities have not touched the Huistas. And, according to local sources, following several weeks of maintaining a low profile they have resumed their activities.

There are a few potential hypotheses — some of which are complementary — that can explain why the Huistas continue to operate with impunity. These hypotheses are based on the field interviews conducted during this investigation.

The first explanation is that the Huistas count on sufficient political protection to keep their leaders immune to investigation and arrest. As was noted in this report, this criminal structure could be linked to an important political party via a congressional representative. But there are no known investigations in the Attorney General’s Office into these ties. What this field investigation was able to confirm was the existence of links between this group and local police, some departmental officials and low-level officials in the Attorney General’s Office.

Nonetheless, it’s necessary to go further to understand the Huistas’ power. Ties to police and the Attorney General’s Office did not save their rivals, nor did contributions to political campaigns. The Huistas have become the local elite through their economic, political and social activities. They are sponsors, benefactors and protectors of the area, in both a symbolic but also in a very real sense. They are the ones who make sure that other criminals (or those from a parasitic state) do not enter and take advantage of a population that has not had a protector for the past 50 years.

The group’s social ties are the key to the second hypothesis. The Guatemalan government seems to pursue criminal structures when they cross the accepted limits on the use of violence: indiscriminate attacks on civilians; attacks against authorities; or armed groups that put into risk the predominance of the security forces, particularly the army. According to a former official in the Attorney General’s Office, the Huistas structure constitutes a “village group” that has limited reach and specializes in the storage and transport of drugs. And they do not, like the Zetas and Villatoro Cano, rely heavily on violence.

From this perspective, the group’s key to survival is due to their apparent decision not to leave their comfort zone — the area where they are based and their established routes; their defense of territory; and their very disciplined use of violence in the areas where they operate, to the point of controlling the violence and crime committed by other criminal groups. This has enabled them to remain out of the crosshairs of the authorities, avoid conflicts with rival groups, and maintain control over the region.

For these reasons, the Huistas were also able to successfully rebuff an attempt by the Zetas to occupy their territory. What the Zetas and their local ally, Villatoro Cano, did not understand was that their one-dimensional strategy of force could not compete against the multidimensional strategy employed by the Huistas. While the Zetas had more gunmen and more weapons, the Huistas had the support of the local population and important links to the state which gave them legitimacy, economic power and, in this case, protection.

The intervening years have provided more evidence of the effectiveness of the Huistas’ strategy. The names of their leaders circulate among international and local law enforcement agencies, but there are no formal accusations, investigations or extradition requests against the Huistas group led by Aler Samayoa.

*This report was researched and written by a Guatemalan investigator who for safety reasons did not want to reveal his/her name. InSight Crime has corroborated the information presented in this report. Map by Jorge Mejía Galindo. Graphics by Andrew J Higgens.

Endnotes

[1] Steven Dudley, “Guatemala Massacre Opens Window into Elite’s Ties to Organized Crime”, 14 February 2013. Available at: /news/analysis/guatemala-massacre-window-elite-organized-crime

[2] elPeriódico, cited by Steven Dudley, “Guatemala Massacre Opens Window into Elite’s Ties to Organized Crime”, 14 February 2013. Available at: /news/analysis/guatemala-massacre-window-elite-organized-crime

[3] Prensa Libre, “Confirman identidad de víctimas de masacre en San Pedro Necta”, 28 December 2012. Available at: https://www.prensalibre.com/noticias/justicia/Confirman-identidad-San-Pedro-Necta_0_836916485.html

[4] On migration from Huehuetenango to the United States, consult: Manuela Camus, La sorpresita del Norte (Guatemala, 2008); Camus (editor), Comunidades en movimiento: La migración internacional en el norte de Huehuetenango (Guatemala, 2007).

[5] Comisión Internacional Contra la Impunidad en Guatemala (CICIG), “El financiamiento de la política en Guatemala” (2015), p. 19. Available at: https://www.cicig.org/uploads/documents/2015/informe_financiamiento_politicagt.pdf

[6] Instituto Nacional de Estadística, “Encuesta de Condiciones de Vida 2014: principales hallazgos” (Guatemala, 2015).

[7] According to Manuela Camus, it is possible to identify the following regions in Huehuetenango: 1) q’anjob’al, including the chujes and akatekos, which were pioneers in the migration to the United States; 2) the southern Mam; 3) The Huista region, which is characterized by diverse ethnicities and the presence of a mestiza population; 4) the awakateka zone, where awakatekos, chalchitekos y kíches live; 5) the multi-ethnic areas that have recently been developed for agricultural purposes, to the north of Nentón and Barillas; 6) the settlements belonging to the ladinos. See: Camus, La sorpresita del Norte (Guatemala, 2008), p. 42-44.

[8] Ibid., p. 45.

[9] Ibid., p. 41.

[10] On the armed conflict in the department, consult: Paul Kobrak, Huehuetenango: historia de una guerra (Guatemala, 2010).

[11] Ibid.

[12] The PAC were groups of civilians who in most cases were forced to complete auxiliary tasks for the counter-insurgency movement, including patrols, controls of towns and routes, and in some instances they assumed real power in the municipalities.

[13] According to CICIG commissioner Ivan Velázquez, “Corruption unifies the Guatemalan political system.” See: Prensa Libre, “Guatemala es propicia para cometer delitos electorales”, 16 July 2015. Available at: https://www.prensalibre.com/guatemala/politica/cicig-presenta-informe-de-financiamiento-de-partidos-politicos

[14] Comisión Internacional Contra la Impunidad en Guatemala (CICIG), “El financiamiento de la política en Guatemala” (2015), pp. 16-19. Available at: https://www.cicig.org/uploads/documents/2015/informe_financiamiento_politicagt.pdf

[15] Jahir Dabroy, Caracterización del sistema político de Huehuetenango: análisis del proceso electoral (Guatemala, 2012), pp. 95-108.

[16] Fundación Propaz’s map of who holds power shows that López Villatoro’s territorial power base is in the central area of the department and the Mam area (south), while a strong relationship with construction businesses permits him channel public funds.

[17] See: Steven Dudley, “The ‘Tennis Shoe King’ Who Became Guatemala’s Gentleman Lobbyist”, InSight Crime, 18 September 2014. Available at: /investigations/guatemala-lopez-villatoro-corruption-lobbyist

[18] On 6 October 2009, the then-commissioner of the CICIG Carlos Castresana denounced, the existence of a network that influenced the process of selecting Supreme Court judges being led by Roberto López Villatoro. The presentation made by Castresana can by found in the following link: https://eleccionmagistrados.guatemalavisible.org/images/stories/notas%20equipo%20Guatemala%20Visible/Presentacion%20candidatos%20a%20CSJ%20Octubre%206-09.pdf and the formal letter to congress can be found here: https://eleccionmagistrados.guatemalavisible.org/images/stories/notas%20equipo%20Guatemala%20Visible/Ref10-2009-162%2005Oct09.pdf

[19] While developing this report, InSight Crime conducted eight field investigations in Huehuetenango, including the department capital and the municipalities of Santa Ana Huista, San Antonio Huista and la Democracia. During the field research we conducted more than 10 interviews and conversations with local authorities, community leaders, politicians, religious leaders and other individuals.

[20] InSight Crime interview with a Public Ministry official that requested anonymity, Huehuetenango, February 2013.

[21] When InSight Crime visited the zone in 2010, several locals talked of more than sixty deaths.

[22] Public Ministry investigators consulted by InSight Crime on why Guatemala City is the origin of various drug trafficking routes, said that drug planes from South America continue to land at La Aurora International Airport. In recent years, authorities have made several seizures in these facilities. With respect to the drug routes from the Southern Coast, the investigators stated the ports are used to receive drug shipments.

[23] This information was provided by an ex-intelligence official who in many cases indicated the name of the legal owner and the name of the legal representative of these businesses. This information was confirmed by interviewees for the businesses in the Huistas region and La Democracia.

[24] elPeriódico, “Los negocios de Palacios, quien murió carbonizado en Huehuetenango”, 28 December 2012. Available at: https://transdoc.com/pagina_interna/25309

[25] Ibid.

[26] InSight Crime’s researcher investigated on his own the prices for the hotel.

[27] InSight Crime interview with a high-ranking military official who preferred to remain anonymous, Huehuetenango, 31 May 2013.

[28] Bureaucratic elites make reference ot the elites that depend on their government posts or their political seats to gain influence and power.

[29] Steven Dudley, “How a Good Soccer Team Gives Criminals Space to Operate”, InSight Crime, 11 June 2014. Available at: /news/analysis/how-a-good-soccer-team-gives-criminals-space-to-operate

[30] Information provided by a district representative that preferred to remain anonymous, Guatemala City, 15 January 2013; an ex-intelligence official corroborated this information, Huehuetenango, departmental capital, 22 January 2013.

[31] According to the press agency Centro de Reportes Informativos sobre Guatemala (CERIGUA), the assassination of the mayor of La Democracia, Huehuetenango in 2010 was attributed to organized crime. See: CERIGUA, “Crimen organizado e intereses personales pintan un panorama electoral sombrío en Huehuetenango”, 5 September 2011. Available at: https://cerigua.org/article/crimen-organizado-e-intereses-personales-pintan-un/

[32] The department of Huehuetenango is an electoral district.

[33] According to statistics from the electoral authorities corresponding to the 2011 elections this district represented 7.2 percent of all voters.

[34] Asociación de Investigación y Estudios Sociales (ASIES), “Partidos Políticos guatemaltecos. Cobertura territorial y organización inerna” (Guatemala, 2013).

[35] In this department during the 2011 elections, voters elected four representatives from the Unidad Nacional de la Esperanza (UNE), four representatives from the Partido Patriota (PP), one representative from the Unión del Cambio Nacionalista (UCN), and one representative from the Partido de Avanzada Nacional (PAN). The representational make-up, however, has since been modified: currently the UNE has two representatives; the Libertad Democrática Renovada (LIDER) party has three representatives; two from the UNE and one from the PAN; one representative from the Unidad Revolucionaria Nacional Guatemalteca URNG – MAIZ party (a post that had been fraudulently assigned to the PP); and an independent representative.

[36] Luis Angel Sas, “Emilenne recargada”, Plaza Pública, 6 July2011. Available at: https://www.plazapublica.com.gt/content/emilenne-recargada

[37] Ibid.

[38] Paola Hurtado, “Marllory Chacón, la reina que abdicó”, Contrapoder, 30 April 2015. Available at:https://contrapoder.com.gt/2015/04/30/la-reina-del-sur-marllory-chacon-la-reina-que-abdico/

[39] Comisión Internacional Contra la Impunidad en Guatemala (CICIG), “Capturan a Ex Vicepresidenta Ingrid Roxana Baldetti Elías y solicitan antejucio contra Presidente Otto Fernando Pérez Molina”, 21 August 2015. Available at: https://www.cicig.org/index.php?mact=News,cntnt01,detail,0&cntnt01articleid=627&cntnt01returnid=67

[40] Instituto Centroamericano de Estudios Fiscales ICEFI, “Guatemala: poder de veto a la legislación tributaria y captura fallida del negocio de la inversión pública”, in Política fiscal: expresión del poder de las elites centroamericanas (Guatemala, 2015), pp. 25-125.

[41] Ibid.

[42] Historically the NGOs in Guatemala have been involved in promoting development projects and civil society initiatives. However, due to a legal loophole, from the 1990s until 2012 NGOs were created that served as intermediaries for public resources. Many of these institutions were created by political structures to capitalize on public funds. In 2012, the Ministry of Finance prohibited the financing of NGOs for public funds.

[43] See: Steven Dudley, “Justice and the Creation of a Mafia State in Guatemala”, InSight Crime, 15 September 2014. Available at: /investigaciones/justicia-y-creacion-estado-mafioso-guatemala

[46] See: https://guatecompras.gt/PubSinConcurso/Proveedores/ConsultaDetPubSinCon.aspx?prv=589040&an=2016

[47] Ibid.

[48] Comisión Internacional Contra la Impunidad en Guatemala (CICIG), “Presentan pruebas contra dos ex policías en caso de desaparición forzada”, 11 March 2015. Available at: https://www.cicig.org/index.php?mact=News,cntnt01,detail,0&cntnt01articleid=584&cntnt01returnid=67

[47] This statement has been made by the Guatemalan newspaper elPeriódico, which has also noted the influence of the Huistas within the local police.

[48] Luis Angel Sas, “Emilenne recargada”, Plaza Pública, 6 July 2011. Available at: https://www.plazapublica.com.gt/content/emilenne-recargada

[49] Ibid.

[50] Soy502, “Definitivo: CC deja sin curul a Emilenne Mazariegos y otros diputados”, 4 January 2016. Available at: https://www.soy502.com/articulo/hichos-mazariegos-arreaga-chavez-quedan-sin-curul-segun-cc

[51] The accusations against this person come from political opponents. There are no formal accusations or investigations against him.

[52] Interview with InSight Crime, January 2013, an ex-member of the Secretary of Intelligence that requested anonymity.

[53] Jorge Dardón and Christian Calderón, “Estudio de caso de la red de Juan Ortíz, alías ‘Chamalé’”, in Ivan Briscoe, et al. (editors), Redes Ilicitas y Política en América Latina (Suecia, 2014), p. 232.

[54] Ibid., p. 234-235.

[55] Charles Parkinson, “Mexico Catches Alleged Ringleader of Guatemala Police Massacre”, InSight Crime, 4 October 2013. Available at: /news/briefs/mexico-catches-guatemala-police-massacre-leader

[56] Siglo 21, 21/09/13, p. 4: Trasiego de drogas está en manos de 12 grupos; Prensa Libre, 12/12/13 pg. 10, Agentes estarían ligados a narcos.

The research presented in this investigation is the result of a project funded by Canada’s International Development Research Centre (IDRC). Its content is not necessarily a reflection of the positions of the IDRC. The ideas, thoughts and opinions contained in this document are those of the author or authors.