Cocaine is a criminal steroid. Those that gain access to its riches enjoy accelerated growth and power – quickly – usually leaving a trail of violence and corruption in their wake. And today, there are more opportunities than ever for criminal groups to access cocaine in both Latin America and Europe.

The cocaine trade has spawned some of the most powerful and notorious criminal structures on the planet. In Colombia, it turned a ragtag band of smugglers into the Medellín Cartel, which declared war on the state itself. In Mexico, it turned rural drug farmers into the heads of multinational criminal conglomerates of astonishing reach and power.

*This article is part of an eight-part investigation that traces the evolution of the European cocaine trade and the Latin American and European criminal networks that have shaped it. The series is the product of field work and investigations over two years in more than 10 countries in Latin America, the Caribbean and Europe. Read the complete investigation here or download the full PDF.

While the US market was initially the main driver of this criminal evolution, over the last two decades the growing European market has also played a key role. In Latin America, cocaine money from Europe has seen Venezuelan corruption networks emerge as major transnational traffickers, while in Brazil it has turned a prison gang into South America’s fastest-growing criminal syndicate. In Europe, meanwhile, while Galician smugglers and Italian mafias were the first to benefit, they were soon joined by others – above all criminal organizations from the Balkans.

Today, the European cocaine trade is more democratized and international on both sides of the Atlantic, with networks cooperating across national and ethnic boundaries. And a historic production boom is offering more opportunities than ever for these actors to get their hands on the cocaine steroid, raising the threat posed by organized crime in Europe.

The Latin American Steroid Effect

In 1976, Pablo Escobar was arrested for trafficking cocaine for the first time when police discovered 39 kilograms of cocaine hidden in the tire of a car he had driven up from Ecuador. When he was arrested for the second time – after 15 years spent trafficking countless tons of cocaine into the United States and Europe – he negotiated his own incarceration into a purpose-built luxury prison.

Between these two arrests, he was elected to Colombia’s congress, then waged a successful war against the government and police, ordering scores of assassinations and terrorist attacks. And he earned enough money to secure a place on the Forbes Billionaire List for seven years running.

SEE ALSO: Colombia News and Profile

When Escobar finally negotiated his surrender, it was only after extradition had been taken off the statute books and on the condition that he could run his own opulent prison.

Escobar ultimately fell not because the state defeated him, but when a civil war broke out between different elements of the Medellín Cartel and many of his own people turned on him. These rebels waged a dirty war against his network, using Escobar’s own tactics against him while cooperating with the security forces.

The fall of Escobar sparked the transition from all-powerful cartels to federations of smaller trafficking groups. But the cocaine trade retained its transformative power.

One of these federations was the paramilitaries of the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia – AUC), a network of allied private armies purportedly formed to combat the threat from Marxist guerrillas, but in most cases more focused on controlling the drug trade.

The AUC used the cocaine steroid to turn themselves into the most fearsome drug trafficking military machine in history, employing brutal and often indiscriminate violence to secure control of coca fields, cocaine laboratories, and major trafficking arteries. When they demobilized in 2006, more than 30,000 fighters handed over their weapons and their dominion of up to a quarter of the country.

As control of the US cocaine trade shifted to Mexico in the 1990s, it was the turn of Mexican organized crime to take advantage of the cocaine steroid.

Today, the most infamous drug trafficking group is Mexico’s Sinaloa Cartel. The Sinaloans began as drug farmers and moved into marijuana trafficking, but it was the cocaine trade that made it what it is today: a multibillion-dollar operation with connections to the upper echelons of the Mexican state and criminal interests in as many as 50 countries worldwide.

However, the European cocaine trade has – and is – transforming criminal dynamics.

One of the first major trafficking routes to Europe outside of Colombia to emerge was Venezuela, which was the main dispatch point for Europe-bound cocaine for the first decade of the 2000s, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). The profits from this trafficking were central to the rise of the Cartel of the Suns – a loose trafficking network made up of high-ranking members of the Venezuelan security forces and government.

Initially, the Cartel of the Suns was little more than a collection of small cells of military officials paid off by traffickers to ensure the passage of their shipments.

“Their job was simply to let drugs enter and move through the country, they would also guard shipments and protect them against hijackings,” Mildred Camero, a former director of Venezuela’s National Commission Against Illicit Drug Use (CONACUID), told InSight Crime.

However, as the European cocaine money rolled in, the ranks of the officials involved got higher and the role they played in the trade got bigger. Today, the president himself, Nicolás Maduro, his family, and many of his top lieutenants have been indicted on drug trafficking charges.

“Now, the problem of drug trafficking goes deeper than you can imagine,” Camero said.

Today, the main trafficking bridge to Europe is no longer Venezuela, but Brazil. Here too, cocaine money has transformed the underworld.

Profits from trafficking to Europe have allowed Brazil’s most feared criminal group, the First Capital Command (Primeiro Comando da Capital – PCC), to complete its transition from a prison gang to a transnational actor with influence in Brazil, Bolivia, and Paraguay, as well as a seat at the top table of the drug trade.

The PCC was already powerful, running not only prisons but controlling criminal enclaves and running criminal economies such as drug sales across swathes of Brazil, especially in many of the urban slums known as “favelas.” Its recent explosive growth is due in no small part to establishing control of several cocaine corridors like that from Bolivia through Paraguay and on to the port of Santos, opening up what has become one of the most important trafficking arteries to Europe, according to Europol.

Police sources in Brazil, speaking on condition of anonymity, described to InSight Crime how the PCC charge independent traffickers to use this corridor. But the top-level leaders – the cúpula – have also leveraged their control over the routes and their growing connections to cocaine brokers and international mafias such as Italy’s ‘Ndrangheta to start moving their own shipments into Europe.

Europe Consumes the Steroid

The effects of the cocaine steroid can also be seen in Europe, where Galician smugglers and the Italian mafia were the first to get a taste.

The Galicians quickly evolved from cigarette smugglers to drug lords, with such corrupting power over local politicians, judges, and security forces that by the 1990s debate raged over the “Sicilianization” of the region – referring to the Italian mafia stronghold of Sicily. In Italy, the cocaine trade turned the ‘Ndrangheta from the poor relations of the Italian underworld to its richest and most powerful actor, far outstripping the famed Cosa Nostra.

But the European market was no monopoly, and as it grew it also democratized, offering access to the cocaine trade to any criminal actor enterprising enough to get a foothold. Chief among them has been organized crime groups from the Balkans, above all the former Yugoslavian states of Serbia, Montenegro, Croatia, and Bosnia, as well as Albania.

The Balkan wars in the 1990s opened the door for organized crime to flourish in the region. Networks formed to traffic arms, people, and drugs – mostly heroin coming from Afghanistan and Turkey. The fighting also hardened people to violence, gave them criminal and military experience and skills, and created a huge diaspora, as tens of thousands of people fled the conflict.

But it was only after Balkan criminals followed the path of the Italians and Galicians into the cocaine trade that they became major transnational actors with a transatlantic presence.

One of the first to do so was Darko Saric, the Balkan “Cocaine King,” who replicated the model of the Italian mafia by building networks not only in Europe but also upstream.

Evidence collected by investigators showed how he exported cocaine to Europe from Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay, while compiling a criminal contact book that included Russian, Italian and Colombian crime syndicates. He also cultivated political ties at home, allegedly with the Montenegrin Prime Minister Milo Djukanovic, and the Serb Minister of Foreign Affairs Ivica Dacic.

However, following a multi-year, multinational manhunt, Saric finally turned himself in to Serbian authorities in 2014 and was sentenced to 20 years in prison.

Today, there are no “kings” of the Balkan cocaine trade, at least not any visible ones. Instead, Balkan criminals increasingly apply a “crowdsourcing business model” to cocaine trafficking, collectively investing in very large shipments, according to the latest annual EU drug report. These are compiled from multiple sources, with Balkans traffickers now buying cocaine directly in Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, and above all, in Peru and Brazil, before organizing its dispatch through ports such as Guayaquil in Ecuador and Santos in Brazil.

Once in Europe, the Balkan mafias break down shipments and move them on to different markets around the continent, in some cases even running “end-to-end” trade – buying in Latin America and selling at the retail level, as some Albanian networks now do in the United Kingdom, according to a Guardian investigation.

Currently one of the most notorious Balkan networks is the Tito and Dino Cartel. Led by Edin Gačanin, the organization has a strong footprint in Dubai and the Netherlands, and Bosnian police believe it controls one third of the cocaine that enters the port of Rotterdam. The US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) considers the network to be one of the 50 largest drug trafficking operations on the planet.

The group is now one of the most important international actors in Peru, intelligence sources told InSight Crime.

“’Tito is the main buyer in Peru,” said one Peruvian intelligence agent who spoke on condition of anonymity. “He has made connections with dispatch networks at the ports of Callao and Piura to send drugs to Europe.”

The network has also played a key role in opening up routes from Chile, the agent added.

“They have migrated to Chile’s port of Arica in order to send drug shipments bound for Europe,” he said.

Peruvian anti-narcotics sources said the organization previously worked with one of South America’s most established trafficking networks, the Andino Cartel, led by the Ecuadorean trafficker Pedro Bejarano, but they severed ties some five years ago. Recent reports indicate they have now cut out the middleman by securing exclusive supply deals with four Peruvian crime clans dedicated to cocaine production.

However, according to the Crime and Corruption Reporting Network (KRIK) and investigative journalist Stevan Dojcinovic, the Tito and Dino Cartel is neither the strongest Balkan criminal group in Peru, nor in Europe. Bigger still, are the Serbs of “Grupa Amerika.”

“Tito is a catchy nickname”, said Dojcinovic. “Every day you’ll find five articles about this, but the truth is there are much more dangerous and bigger players than Tito.”

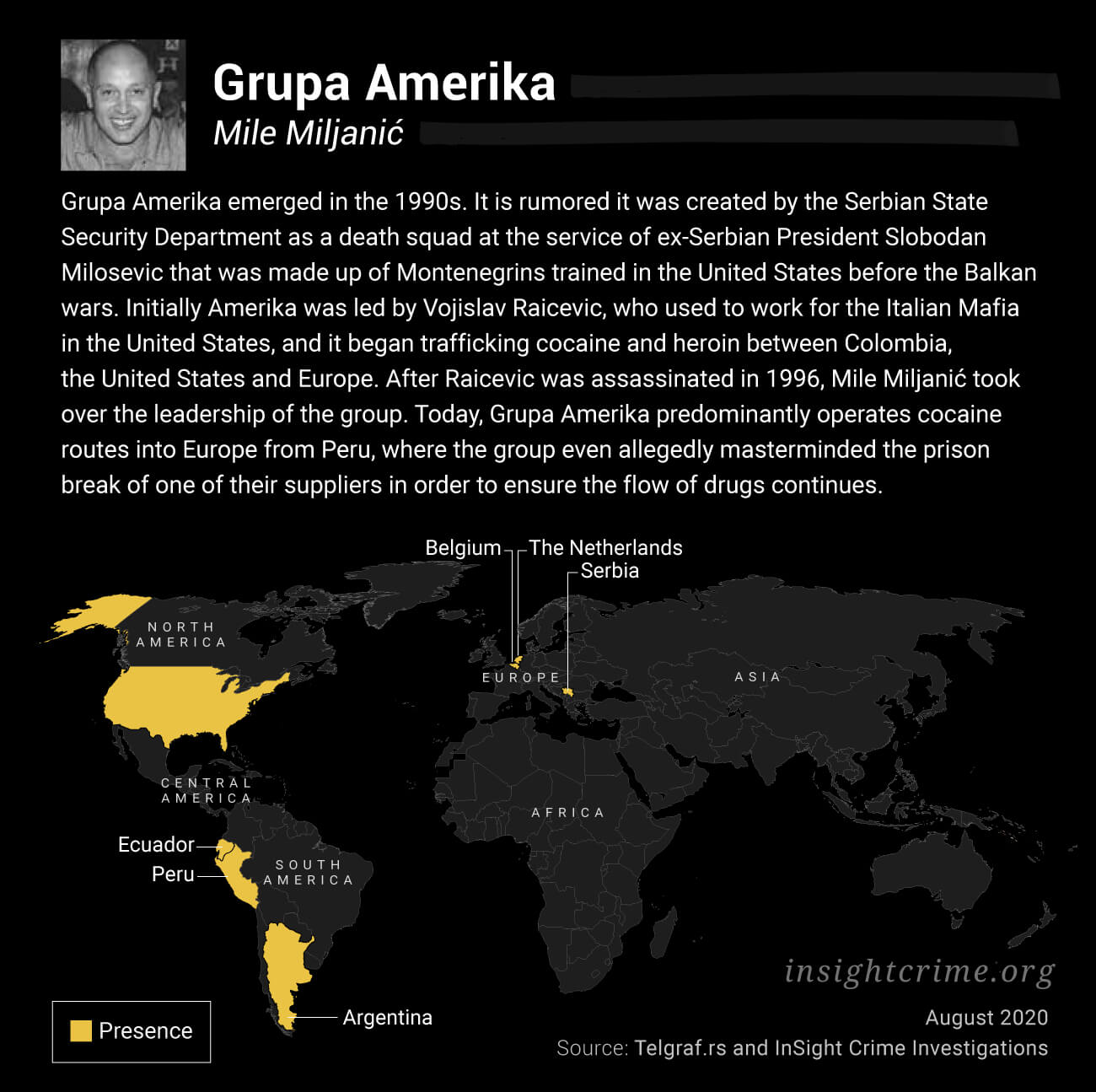

Led by Mile Miljanić, Grupa Amerika was born 30 years ago on the streets of Belgrade, and today it is one of the most powerful Serb networks in South America. However, evidence of Grupa Amerika’s presence in the region is elusive, with only one high-profile arrest linked to the group.

This came in July 2016, when Peruvian police captured Balkan War veteran Zoran Jaksic in the city of Tumbes as he tried to cross the border into Ecuador with over 40 false identities and 10 passports in his luggage.

Jaksic is suspected of smuggling hundreds of tons of cocaine into the Netherlands and Belgium, and was a wanted man in 25 countries. He was based in Argentina and bought cocaine in Peru and Ecuador, then turned it into liquid form and exported it to Europe in shipments of wine bottles.

European groups such as Tito and Dino, Grupa Amerika, the ‘Ndrangheta and the Galicians have grown enormously wealthy and powerful off cocaine. But unlike the Mexican cartels in the United States, none of them have the capacity to shut other European actors out of the market.

Irish, British, French, Dutch, Turkish, and Belgian actors also play a key role in the supply chain both up and downstream, and InSight Crime has also received reports of the growing presence of organized crime groups from Russia and other former Soviet states in Latin America.

Furthermore, in today’s ever more fluid underworld, none of these groups have the capacity to run cocaine routes from production to retail single-handedly. Instead, they constantly form and dissolve networks and alliances with different actors from all across the globe.

In this democratic, decentralized, and multinational underworld, criminal networks involved in cocaine trafficking are multiplying on both continents. And many of them get their hands on the cocaine steroid by moving up the supply chain, thus increasing their profits. All they need is money and the right contacts: a broker that can source cocaine, and a logistics specialist to traffic it – above all those that have mastered the complex world of container shipping.

*Investigation for this article was conducted by James Bargent, Douwe den Held and Owen Boed.