The FARC’s pledge to end its war to overthrow the Colombian state is a huge step forward in reducing the country’s violence. But an end to the five-decade old civil conflict is still far off.

Here are eight reasons why, even should the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia – FARC) disarm and demobilize today, the civil conflict will continue:

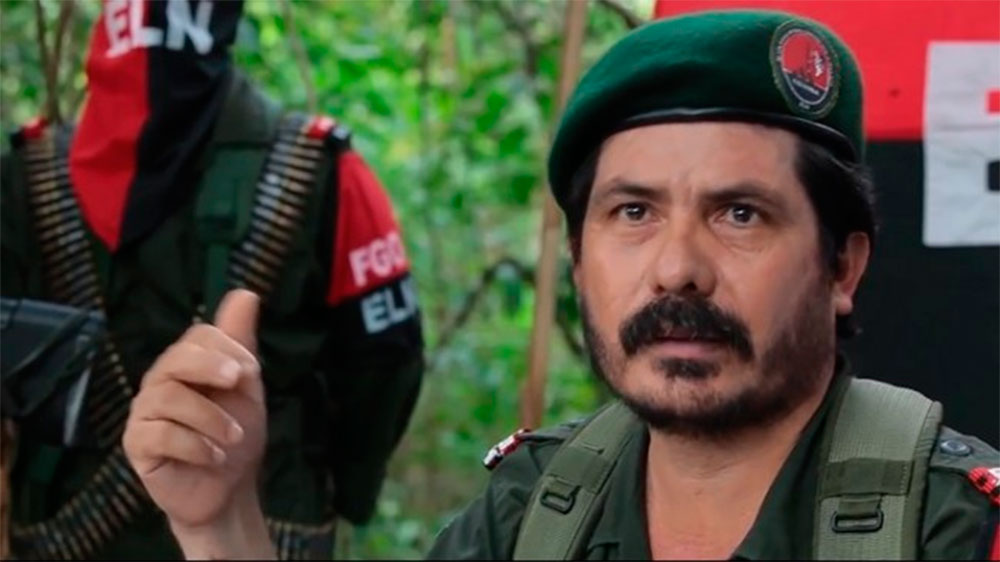

1) The ELN Remain in the Field

Even if the FARC sign a final peace agreement, the 2500-strong National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional – ELN) is still active and expanding. Like the FARC it is a Marxist Leninist group with 54 years trying to overthrow the state. The peace process with the ELN has still not begun and seems unlikely to do so any time soon. President Juan Manuel Santos has demanded that the ELN abandon the practice of kidnapping as a precondition to sitting down to dialogue. The FARC agreed to these terms, but so far the ELN “First Comandante,” Nicolás Rodríguez Bautista, alias “Gabino,” while stating that they have reduced kidnappings, will not commit to halting the practice. Perhaps because he cannot guarantee that all his units would obey such a ruling.

2) ELN a Different Negotiating Challenge

Even if a serious peace process with the ELN were to start tomorrow, the chances of negotiating a meaningful deal with the more fractured and federated ELN structure are far harder than with the vertically integrated and disciplined FARC. While it would seem straightforward that the ELN sign the same deal as the FARC, the smaller group believes that civil society must be involved in the process, another factor that could draw out negotiations.

3) Divided ELN Command Structure

While the ELN has its Central Command (Comando Central – COCE), the equivalent of the FARC’s Secretariat, it appears divided over the issue of peace talks. InSight Crime field research in Arauca, along the border with Venezuela has shown that the newest member of the COCE, Gustavo Aníbal Giraldo Quinchía, alias “Pablito,” is against dialogue under the current conditions. Military intelligence sources have also suggested that Pablito is now the military head of the ELN, replacing Eliécer Erlington Chamorro Acosta, alias “Antonio García,” who is handling negotiations with the government. He also commands the ELN’s richest, most powerful and most belligerent War Front (Frente de Guerra) or fighting division, which is based in Venezuela and active in the Colombian departments of Arauca, Boyacá, Casanare and Norte de Santander.

4) Transfer of FARC Resources and Criminal Economies to the ELN

There is already evidence in certain parts of the country, like in the north of Antioquia, of a transfer of men, weapons and criminal economies from the FARC to ELN units. This is a pattern that is likely as FARC elements unhappy with the signed agreement or unwilling to abandon the armed struggle, ally, affiliate or join their ELN cousins.

5) The Drug Boom

The ELN are likely to deepen their involvement in drug trafficking and strengthen their finances. Over the last two years the sowing of coca crops and the production of cocaine has doubled. This means that the earnings of the illegal actors have increased exponentially. While the ELN until 1998, under their previous commander and former Spanish priest, Gregorio Manuel Pérez Martínez, alias “El Cura Pérez,” kept a distance from drug trafficking on ideological grounds, today many units of the ELN are as involved in the drug trade as their FARC cousins and Pablito now has an extradition request from the US to face narcotics charges. Transnational organized crime always wants to see rebels remain in the field as they have traditionally controlled the production end of the business and protected drug crops.

6) Risks of FARC Dissidents

All it takes is enough middle ranking commanders, or one senior commander with status in the movement, to continue the armed struggle, for a “Real” or “Continuity” FARC to remain in the field with a revolutionary message and insurgent façade. There are already precedents for this. With the 2006 demobilization of the right-wing United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia – AUC) a new generation of criminal groups known as the BACRIM (from the Spanish “bandas criminales”) were born overnight, under the command of middle ranking leaders, claiming a paramilitary heritage. On the rebels side there is the case of the Popular Liberation Army (Ejército Popular de Liberación – EPL). While most of the movement demobilized in 1991, about 20 percent of the rebels refused to hand in their weapons and remained in the field. The last bastion of this group is present in Catatumbo, in Norte de Santander, and is currently expanding its presence and strength thanks to deep involvement in the drug trade, maintaining its ideological façade and working closely with local communities in its areas of operation.

7) Assassinations of FARC Leaders

One of the greatest challenges to a lasting demobilization is the risk of assassination of FARC leaders as they leave their mountain and jungle strongholds and enter political life. The murder of up to 4,000 members of the Patriotic Union, the FARC’s 1980s effort to enter the political mainstream, still casts a long shadow over the rebel movement. Land restitution activists, trade union leaders, community leaders and local left-wing politicians continue to be killed with frightening regularity. A sustained assassination campaign against FARC members after an agreement could push rebel elements back into the jungle to take up arms once again.

8) Chaos in Venezuela

Both the FARC and ELN have significant presence in Venezuela, which has long been a rearguard and logistics area for them. With the economic collapse in Venezuela and the political fighting, the risk of civil unrest, and even civil conflict, grows. Should there be a collapse in Venezuela with an open conflict, both FARC and ELN elements may decide that the revolutionary struggle can be continued in, and from, Venezuela, giving a new lease of life to the Colombian insurgency. The situation in Venezuela also makes any claims of a possible military victory over Colombian rebels hollow. If the rebel leadership lives in Venezuela, has access to arms and money there, why would they expose themselves to bombardment in Colombia?