A former El Salvador security minister told El Faro that he believed the truce between the country’s two main street gangs, MS13 and Barrio 18, was over, and called for any future agreement to be transparent, and to involve the disbanding of the gangs.

Francisco Bertrand Galindo, known as “Chico” by his friends, was security minister for the first three years of the government of former President Francisco Flores, between 1999 and 2002. He left the post a year before the implementation of the Plan Mano Dura (Iron Fist Plan), the public policy that most strengthened the maras.

More than a decade has passed, and many believe that the famous 2012 “gang truce” is the public policy that has most influenced the evolution of the gangs since the Iron Fist — although the last government left office without accepting its key role in the initiative.

The following are excerpts of the El Faro interview with Galindo. A version of this article originally appeared in El Faro’s Sala Negra and has been translated and reprinted with permission. See the original article here.

***

Is the truce broken?

First let’s define “truce.” If we understand it as an agreement between the Mara Salvatrucha (MS13) and Barrio 18 not to fight, I believe that was never consolidated, particularly due to problems between the Barrio 18 factions, the Revolutionarios and the Historic 18 [a reference to the Sureños faction]. The agreement between the gangs had a certain validity until [Security] Minister Ricardo Perdomo arrived [at the end of May 2013]. It was not automatic, that Perdomo arrived and the truce ended, but he cut off the communication channels between imprisoned leaders and gang members on the streets, and that had consequences.

But the truce also involved the government.

That is the other concept of the truce.

The authorities repeated ad nauseam “We didn’t have anything to do with it.” Do you believe this rhetoric?

Of course not. I don’t know if the dialogue with the gangs began with the OIE [the state intelligence agency], or if it was an initiative of Minister [David] Munguia Payes, or if Raul Mijango [a key intermediary in the truce] convinced the minister… but, viewing it from the outside, it seems like what happened was that Munguia Payes first promoted the militarization of public security like never before, and that provoked the gangs to systematically attack the military. I don’t know if that made him reflect, but the point is that he suddenly changed strategies. I think that is why the agreement between the gangs and the government happened — so that they would stop killing soldiers and police and people using public transport, and so that they would respect the schools. Those were the three promises that the gangs made in exchange for the government moving their leaders from Zacatecoluca to other medium-security prisons, liberalizing visiting protocols and lowering the internal pressure.

Attacks by the gangs on police and soldiers have increased in recent weeks.

That’s true, and that’s why I believe that the truce is over in both senses: both between the gangs and between the gangs and the government.

There are well-informed people, like the truce’s mediators, who say otherwise.

In my opinion, the process that began in 2012 has finished, but there could be a new attempt to establish another agreement — it seems logical. It is not good for any society if criminal gangs are killing each other. Some may think: they are criminals, it is better that they die, but in these wars there is always a lot of collateral damage. In the madness, civilians die who are not part of the groups, and family members, and it creates a general atmosphere of insecurity that is not good for any country.

I suppose you are not referring just to El Salvador.

No. Throughout the world, when a war breaks out between criminal groups, the authorities try to calm things down. But how do they do it? Well, when there are strong institutions, normally they try to correct the principal problem that led to the conflict between the groups. The problem with the maras in El Salvador is that this cannot be done, because it is something so big, the chain of deaths is so long, that ending the fighting between them is not easy.

SEE ALSO: El Salvador Gang Truce: Positives and Negatives

You are convinced that the truce is over. Would it make sense for El Salvador to begin another, similar process?

Look… if this implied the work of citizens who tried to convince the gangs not to kill each other, or to reduce the level of danger they pose to civilians, that would seem like a legitimate process to me. What I do not think is legitimate is when the state begins negotiations that do not have the ultimate goal of disbanding the gangs. I do not think it is bad for the state to offer specific benefits, or even a pardon or an amnesty, to those who decide to leave the gangs. That would seem transparent and logical to me, if it were done through legal means. If it generates the need for mediation, that also seems logical to me. And if in the course of things they needed to speak [with the gangs] to make secondary agreements, that would also be fine. What I do not think is logical is to speak of “peace agreements” with criminal groups, if nobody is putting on the agenda that they stop being criminal groups.

You have been a clear opponent of this process, and you have expressed as much in everyone television appearance you have made.

Yes, that’s right.

SEE ALSO: Barrio 18 Profile

I’d like to focus on the issue of homicides, which is what make the Salvadoran case unique. During the truce, murders fell from 4,000 to 2,300 [annually]. How can a process that saves 1,700 lives a year be harmful?

The response to this type of question is not simple. In the first place, homicides in El Salvador depend on regions and certain types of people. I would go so far as to say that 80 percent of homicide victims have been contributors to homicides; that is to say, they are criminals too. But obviously there are also some people killed who are strictly victims.

Do you distrust the official figures? There were truce critics, particularly at the beginning, who said that the police were manipulating the numbers.

No, I don’t think that they stopped counting deaths, but it has been proven that after the truce many of the “disappeared” ended up in clandestine graves.

True, but before the truce the same thing happened… disappearances and clandestine graves did not suddenly become a phenomenon in 2012.

I think that the number increased.

You believe that the nearly 1,700 people whose lives were saved, according to the statistics, were really buried in the cornfields?

No, I don’t believe that, not even close. I have no doubt that with the truce there was a drop in homicides. We are clear that the numbers fell, but the society perhaps did not see it this way because, in some way, homicides are accepted as normal.

Sadly.

Sadly, but it has been that way since long before the gangs. In El Salvador we have had incredibly high homicide rates at least since the 1960s, and I say that as a way of explaining how Salvadorans relate to homicides. They see them as something distant, because they assume that the dead person owed something or had done something. That perception exists. That would explain why, despite the fact that homicides fell as much as they did, surveys indicated that insecurity continued to be the biggest problem, because homicides are not the principal indicator for Salvadorans — the feeling of a lack of security is fed more by robberies and extortion.

…

Another idea that has been put forth is that the reduction in homicides only benefited the gangs. Do you share this view?

I don’t have the figures, but I do think that a good percentage of the deaths that occurred before the truce were linked to criminal organizations, and I am not referring just to the gangs, which there is evidence of, but also to drug trafficking groups and others… There are always collateral victims, but the reduction in homicides has benefited those groups.

SEE ALSO: MS13 Profile

Even supposing that the decrease was due in great measure to gang members no longer dying, wouldn’t that also be beneficial for society due to the simple fact that they wouldn’t have to be recruiting as many members, many times by force?

That is a good point, and I will admit that I had not looked at things from that perspective.

Do you think the truce has perhaps benefited families living in communities under mara control?

I once heard Rodrigo Avila say: this [initiative] would make sense if the result were that the number of gang members did not grow. And from Raul Mijango I heard another idea: he said that the adult gang members were tired of that life, that they did not want it for their kids and that it was logical that a deterioration of the [gang] phenomenon would occur. I give you both those points, from people who think so differently, and now I will give my view: I think that the truce has strengthened the gangs — that the number of gang members has increased — but it is also now true that they don’t have as much need for forced recruitment. Many mothers today can thank the truce that their children were not forcibly recruited, as happened before.

Both options must be examined: first, look for a way to cut out the gangs’ social base, or at least make it difficult, and second, how to rescue all of those kids that probably should not even be in prison, because the same sentence was applied to an entire clique [faction of a gang], when not everyone in the group played the same role. Among the gang members there are psychopaths, and they should be treated as such, but at the same time, within the gangs there are youths who perhaps would want to leave that world if they were given the opportunity. All of those nuances, those differentiations, are important for the people formulating public policies to bear in mind.

Do you believe that the maras are now more dangerous than they were in March 2012?

I would need to have the figures… What I do believe is that they have strengthened.

For you, “strengthen” and “be more dangerous” are not synonyms?

It depends on how we look at it. If I analyze it as the state, their being stronger does make them more dangerous. But for a common citizen, being stronger does not necessarily mean being more dangerous, if the gangs are involved in crimes that do not directly affect the public. A group can be more powerful, but it could be so because it moves shipments of drugs from border to border, and that doesn’t affect civilians.

Being pragmatic, wouldn’t that scenario be better than that which we had at the beginning of 2012, or that which we currently have?

Of course that would be an improvement. People don’t measure the sense of insecurity by the operations of a cartel that moves drugs to the United States, but by the small-scale violence generated by local drug sales. The neighborhood gangs do generate a sense of insecurity because they threaten people, because they demand money…

Do you think it is a possibility that the strengthening of the maras during the truce could be a false perception, which is in the interests of some powerful groups to spread?

I am convinced that they have grown stronger.

…

Let’s come back to the present. Do you believe that the new government will enter new negotiations with the gangs?

The dangerous thing in all of this is if a government, of any party, tries to construct an organization that operates parallel to the state and has political objectives.

Won’t that possibility disappear if as a society we demand a transparent process — the opposite of what the previous administration did?

I have believed something like that for years. The issue of security needs to be taken out of the electoral discussion, and political controls need to be put in place, because, if not, the distrust between the two principal parties is going to continue, for fear that anything that is done will respond to interests unrelated to public security. And how can political controls be put in place? In other countries they have created a type of special commission in which all parties have a presence. What is discussed there is confidential, but those responsible for public security, at all levels, are required to report on the steps taken. Mechanisms like that have worked in other countries.

With the polarization that exists in El Salvador, could a commission of that kind exist?

It is what is most urgently needed; if not, they are not going to be able to put anything serious in place, and if they tried, the opposition would be fierce. The gang problem will only be resolved if the authorities recover territorial control of the communities and construct social networks, support networks… and these networks may be politically neutral or politically slanted. Any party that is in opposition is going to prevent politically active networks from being created, and in order to prevent this it is useful to create control mechanisms and remove the issue from the electoral agenda.

Put that way, the political party polarization is the principal obstacle to dealing seriously with the issue of violence.

It has always been that way.

…

Let’s suppose this cycle of skepticism were to be stopped. Do you think that afterwards the citizenry would accept that the state direct millions of dollars into the rehabilitation of gang members, or into prevention in the communities they control?

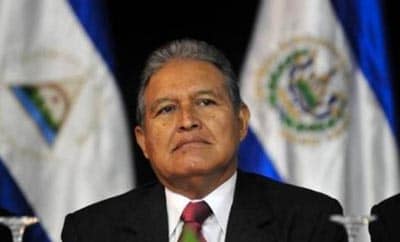

That is why the president is such an important figure. Look, what I most liked about the discourse of [new President Salvador] Sanchez Ceren was when he said that he was taking care of the citizen security problem — he didn’t say “public security,” but rather “citizen security.” To me that seemed like a radical change, because that is the only way to guarantee that when the state recovers control of the territory, they will get the Education Ministry, the Health Ministry, the FISDL, Public Works involved… The president is the only person who can order all of this to happen.

Do you have hopes that during the current term the political polarization that exists will be ended?

I hope so, and I hope so for a simple reason: an FMLN government is closer to calling for a national agreement and bringing all of the forces together. I know this might sound strange, coming from someone who has worked for administrations led by ARENA, but I think it would be difficult to get the FMLN on board with an agreement called for by ARENA, while I see the reverse as being more probable. So, that is something that makes me optimistic.

You also said the discourse of the new president provoked optimism.

That as well, although it remains to be seen whether that will translate into actions. Mauricio Funes said that the values of Bishop Romero were going to guide his actions, and look what happened. But if President Sanchez Ceren said that seriously, I have real hope that a national agreement can be put in place, and in order for this agreement to be effective, we need those political controls. That is why I am so insistent on that point. We will also need limits on police and army operations, and all of those things, because the devil is in the details. The agreement needs to reach those levels.

So there is reason for optimism?

I think an agreement can be reached during this administration.

*A version of this article originally appeared in El Faro’s Sala Negra and has been translated and reprinted with permission. See the original article here.