New data on Mexico’s female prison population suggests a rise in the number of women behind bars for involvement with criminal groups. However, a detailed analysis reveals a more nuanced reality.

Data published by Mexico’s National Institute of Statistics and Geography (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía de México – INEGI) shows that between 2017 and 2022, the number of women either sentenced or in pretrial detention for offenses associated with organized crime* grew from 9,754 to 11,295, an increase in the prison rate from 15 per 100,000 people to 17 per 100,000 people.

The number of men arrested for crimes associated with organized crime rose even more sharply during the same period, going from 215 to 241 per 100,000.

SEE ALSO: Women Increasingly Participating in Organized Crime in Mexico: Report

Homicide and kidnapping were the most common crimes for which both men and women were increasingly detained, which coincided with the rise in rates of violence in Mexico during the period. Although the number of women in prison for homicide remained stable, kidnapping offenses registered a sharp increase in 2022, rising 73% compared to 2017.

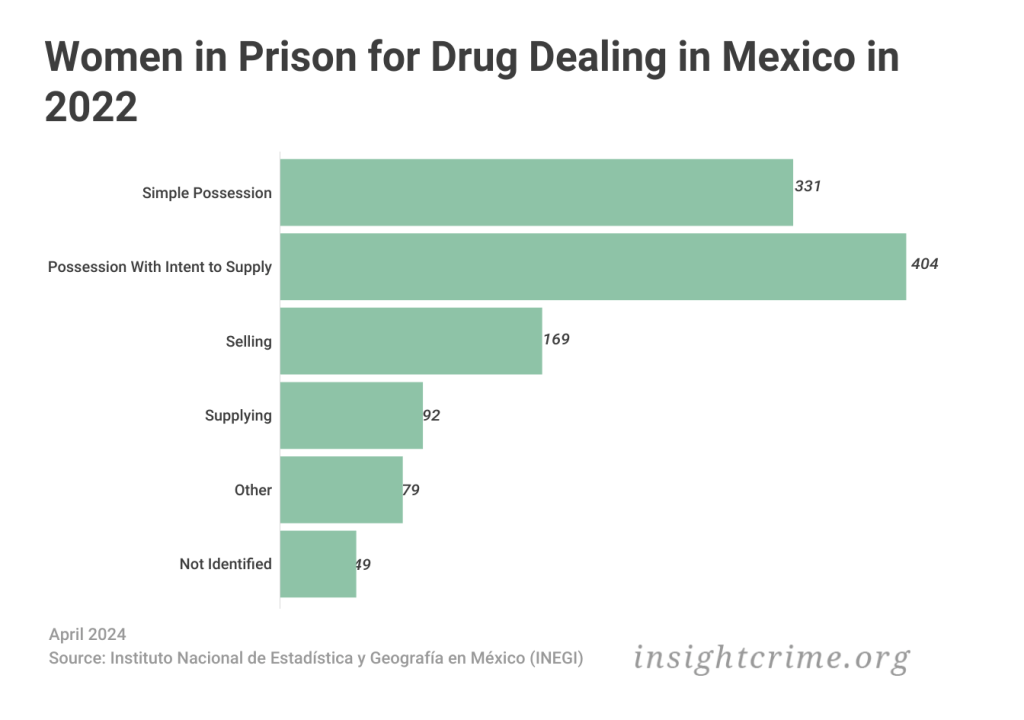

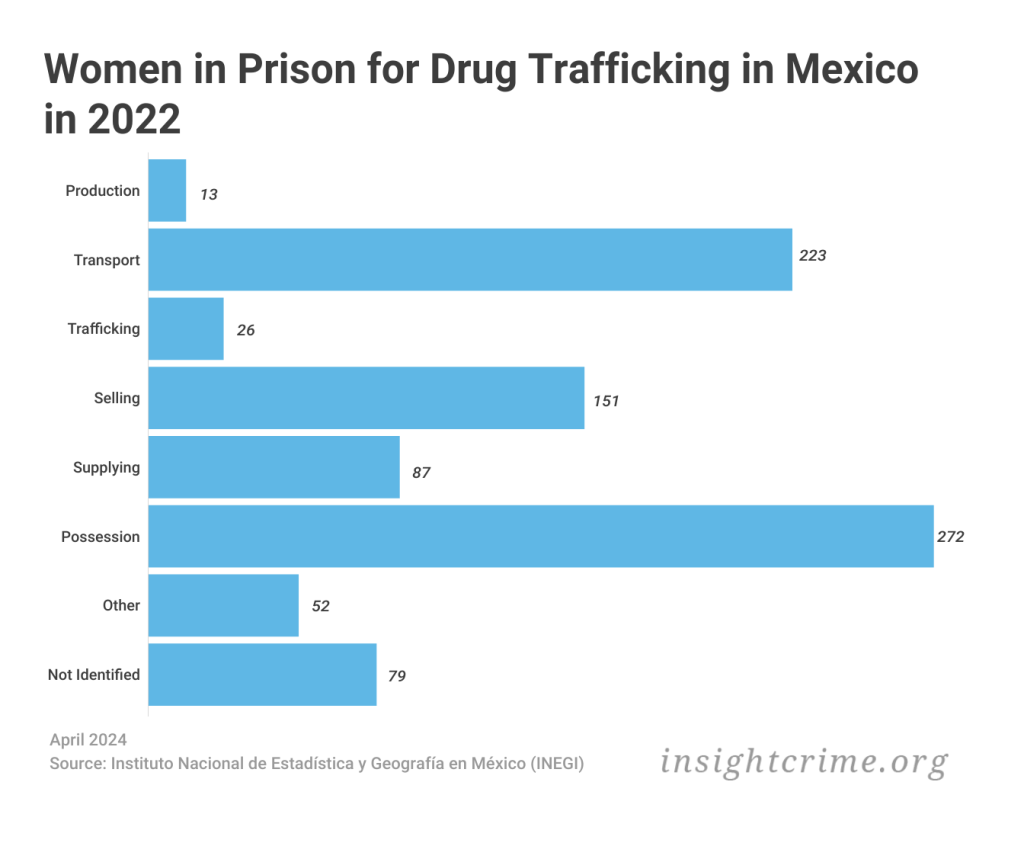

Weapons-related crimes, drug dealing, and drug trafficking were the next most common crimes for both sexes. The number of women in prison for weapons offenses grew 75%, while drug trafficking offenses jumped 35%.

The number of women in prison for involvement in forced disappearance jumped by 6,800%, while the number for smuggling undocumented persons increased by 278%. Previously, only two women were imprisoned for forced disappearances, and just four women for smuggling undocumented persons.

This data comes at a time when several studies have found that the role of women in Mexico’s organized crime groups is diversifying.

A report by the International Crisis Group published in 2023 found that more women are participating in organized crime groups to gain power or protection in the context of increasing gender-based violence in Mexico.

In multiple investigations, Cecilia Farfán-Mendez, a researcher at the University of California San Diego and an expert on organized crime, has found that women assume various roles within organized crime structures, despite gender-role stereotypes and gender-based violence by both criminal actors and authorities.

Women in Prison

INEGI’s data suggests that there are a significant number of women involved in high-impact crimes like homicide and kidnapping. However, in many criminal economies like arms or drug trafficking, the women arrested are usually in the lower ranks of supply chains.

For example, 65% of the women imprisoned for drug dealing in 2022 were charged with simple possession and possession with intent to supply. In the case of drug trafficking, 30% were arrested for possession and 25% for transporting drugs.

This same dynamic is repeated in weapons-related crimes. Ninety-three percent of women were imprisoned for carrying and possession, compared to 1% who were detained for trafficking.

The trend is similar for men, but a higher proportion of men were arrested for their alleged involvement at the higher end of criminal economies, like supplying and trafficking of weapons and drugs.

Farfán-Méndez believes that this disparity in arrests could be related to the current strategy against drug trafficking, which has focused on addressing the problem from a criminal rather than public health perspective.

“When there are punitive approaches, it is precisely the most vulnerable people who end up in prison,” she told InSight Crime.

Angélica Ospina, a researcher with the International Crisis Group, noted two other reasons to explain this dynamic. On the one hand, most women involved in drug trafficking networks are at the bottom of the structure, rather than in leadership positions, which increases their chances of being arrested, she explained.

On the other hand, many of the women in the lower links are in precarious economic and social situations, lacking the resources and support necessary to defend themselves legally or finance their release from prison. Criminal groups often do not support them either.

“They don’t offer support because [they see the women] as easily replaceable,” Ospina told InSight Crime.

In part, the lack of legal support is reflected in the data. According to INEGI, women accused of organized crime offenses are more likely to remain in pretrial detention compared to men. For example, by the end of 2022, 47% of women had not been sentenced, compared to 36% of men on trial for the same crimes.

Congruence with Local Criminal Dynamics

The geographic concentration of women prisoners seems to coincide with the criminal dynamics that predominate in each state and with the trends that have developed in Mexico’s illicit markets in recent years.

In 2022, Baja California was the state with the highest rate of women imprisoned for crimes related to organized crime, with 29 women per 100,000 inhabitants. Homicide, drug trafficking, and drug dealing were the most common crimes women were charged with there, coinciding with the local criminal dynamics. Baja California’s shared border with the United States is a major crossing point for all kinds of illicit drugs coming up from Latin America, not just Mexico, as well as undocumented migrants and human trafficking victims. Multiple criminal groups, including factions associated with the Jalisco Cartel New Generation (Cartel Jalisco Nueva Generación – CJNG) and the Sinaloa Cartel, fight for control of the border.

The violence is also linked to the state’s local drug market. Various security institutions in Baja California interviewed by InSight Crime in late 2022 said that the majority of homicides there are linked to gangs’ attempts to control the local drug market and sales points. As a result, cities like Tijuana register some of the highest homicide rates in the country.

SEE ALSO: Women in the Room: Q&A With Narcas Author Deborah Bonello

Chihuahua has the second-highest concentration of women in prison. In fact, the state more than tripled its rate of women behind bars between 2017 and 2022, from 5 to 17 per 100,000 people. Drug trafficking, drug dealing, and homicide were once again the most common crimes. And, like Baja California, the state is a major corridor for illicit drugs and has historically seen high homicide rates, particularly in the border city of Ciudad Juárez.

Ospina asserts that protecting themselves from this widespread violence is one of the main reasons why more women decide to join criminal organizations, and could explain why these two states have the highest numbers of women in prison in Mexico.

Farfán-Méndez, however, stresses that prison figures are primarily an indication of law enforcement trends, which may explain why increases are seen more in some states than others.

“In Baja California, for example, there have been several [police] operations in recent years, precisely to [control] the border,” she said.

The types of crimes for which women are detained also differ geographically.

For example, in Jalisco, there has been a steady increase in the number of women charged with forced disappearances between 2017 and 2022. This coincides with the crisis of missing persons in the state, caused, in part, by the CJNG’s attempts to establish territorial and social control, while keeping street violence rates low. Jalisco is the organization’s base of operations and has the highest number of missing persons in the country. More than 14,700 people have been forcibly disappeared there.

On the other hand, the highest number of women arrested for extortion and kidnapping for ransom is in the State of Mexico, with 198 and 951 cases respectively in 2022. This number can be partly explained by the state’s high population, but the central region of the country, where Mexico State is located, has also seen higher rates of extortion over the past six years.

Extortion is often carried out by criminal groups such as the Familia Michoacana, remnants of the Knights Templar and the CJNG, and has affected the transportation and food industries.

According to Ospina, the apparent increase in women’s involvement in extortion, and other violent crimes such as homicides and kidnappings, also reflects a growing desire these women have to rise up the ranks of criminal groups that have used violence to achieve their objectives.

“If [women want] to move up, they have to be willing to inflict and receive violence,” Ospina concluded.

*Methodological note: We consider the crimes associated with organized crime to be drug dealing, drug trafficking, extortion, homicide, kidnapping, weapons-related crimes, forced disappearance, human trafficking, trafficking of minors, smuggling of undocumented persons, vehicle theft, organized crime, fuel theft, and environmental crimes.

Featured Image: Prison guards stand in formation in the women’s section of the federal prison in El Rincón, in northwestern Mexico. Credit: Associated Press