Vehicle theft is back on the rise in São Paulo following years of decline, as criminal groups exploit supply chain issues to revive a withering black market.

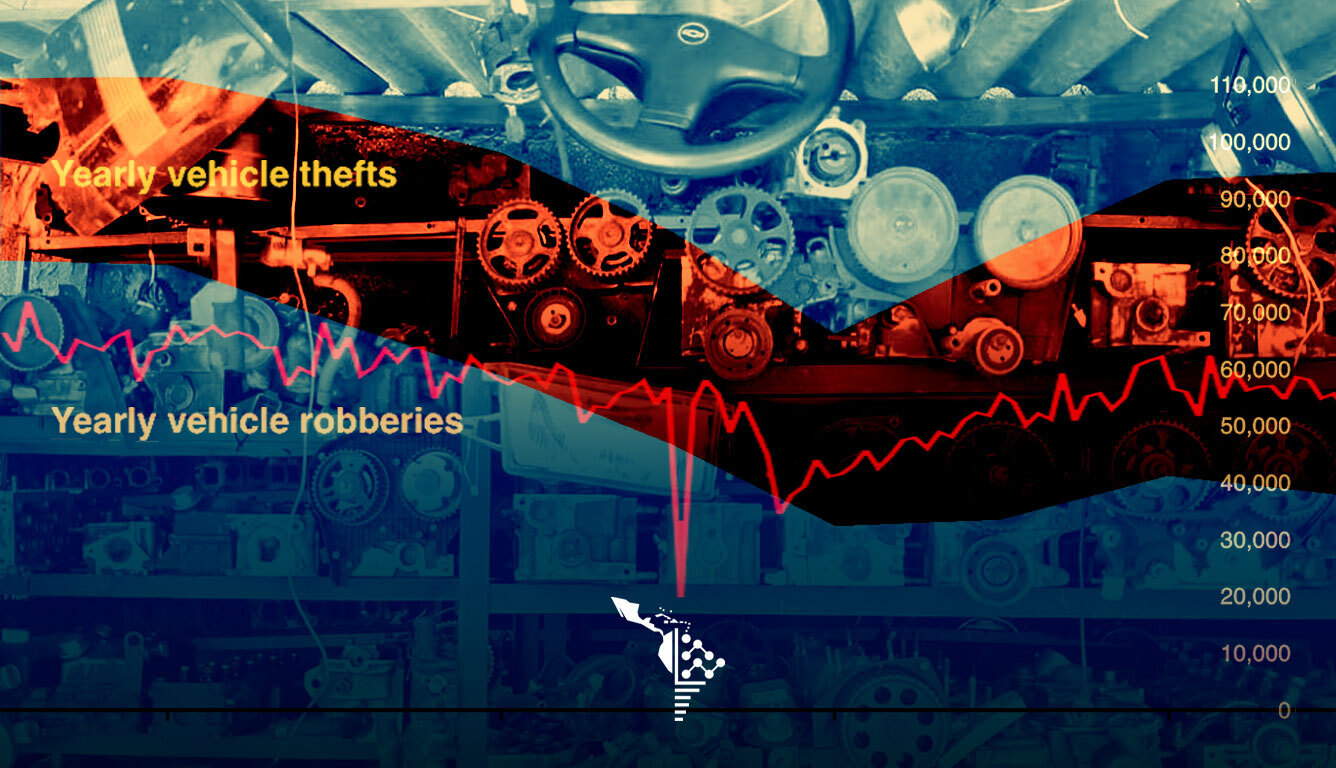

Brazil started to see a nationwide increase in vehicle theft around 2020, but no state has seen a spike as dramatic as São Paulo. Car thefts in the country’s most populous and economically important state rose from a low of 65,724 in 2020 to a total of 94,258 in 2023, according to data from Brazil’s National System of Information on Public Security (Sistema Nacional de Informações de Segurança Pública, Prisionais, de Rastreabilidade de Armas e Munições, de Material Genético, de Digitais e de Drogas – SINESP) and São Paulo’s Secretariat of Public Security (Secretaria da Segurança Pública).

Car theft, where the car is stolen without the use of force, is much more common in São Paulo than robbery, where threats or violence are used.

São Paulo is the epicenter of Brazil’s vehicle theft industry

Number of vehicle thefts in Brazil (2015-2022)

Stolen cars in Brazil mostly contribute to the broader industry of contraband vehicle parts. Thieves tend to avoid luxury vehicles, for which there is limited black market demand. Instead, they focus on popular but inexpensive models whose parts will be in high demand. Small groups of thieves, or even individuals, bring them to chop shops where they’re bought and stripped for parts. Their new owners then undercut market prices with cheaper, contraband products. In São Paulo, these illegal chop shops – like most criminal economies – are controlled by Brazil’s most powerful criminal group, the First Capital Command (Primeiro Comando da Capital – PCC).

The PCC, a prison gang from São Paulo, expanded beyond prison walls to become an international criminal organization. The group now dominates several criminal industries in its home state, where it has pushed out all criminal competition. With chop shops dotted around São Paulo, there is little preventing would-be thieves from offloading stolen cars in stores likely run by the PCC.

“The vehicle already has a set destination, the car is going to be stripped and the parts are going to be sent to these illegal chop shops,” Aline de Lima e Lins Rocha, a São Paulo police delegate, told InSight Crime.

Why Car Theft Stalled

The spike in car theft comes after a period of decline that followed the passing of Brazil’s chop shop law in 2014. The law prohibits the dismantling of vehicles and reselling of their parts, unless it is done in an authorized shop registered with the state. The legislation also requires vehicle parts to be registered and allows authorities to inspect a shop without prior notice.

São Paulo’s state government went a step further in 2015, announcing that all car parts must have a QR code tracing their history. Anyone with a smartphone could see where the part came from, and shops had to update the system with every part they sold. “All these regulations from the chop shop law deter and end up reducing – in particular – car robberies,” PCC expert Janaina Maldonado told InSight Crime.

She added that robberies – cars stolen using force –- are generally reported to the police faster than non-violent vehicle thefts, so the parts show up in the system as stolen. With chop shops registered and monitored by the government, many owners did not want to risk getting caught with stolen parts. This left robbers with fewer locations to flog stolen cars. As a result, vehicle robberies became a less appealing criminal economy, Maldonado told InSight Crime.

Vehicle thefts plummeted from 110,690 in 2015 to just 65,724 in 2020, according to SINESP’s data. São Paulo recorded an even sharper drop in car robberies during the same period, decreasing from 78,659 in 2015 to only 31,893 in 2020.

Vehicle robberies and thefts crashed after Brazil passed its chop shop law, but thefts are rising again

Number of vehicle thefts and robberies in São Paulo state, Brazil (2015-2023)

Around the same time the chop shop law was passed, Brazil started importing lots of cheap, legal car parts from China. With the government cracking down on contraband, and legal auto parts becoming cheaper and increasingly available, illegal chop shops began to make less sense. The PCC, which ran most of these illegal shops in São Paulo, was focused on other illicit economies that it monopolized in the state, such as the drug trade, according to a 2023 study co-authored by Maldonado.

With illegal chop shops shutting down and legal businesses losing interest in stolen parts, stealing vehicles became less profitable. “As soon as we started tackling the chop shops, thefts automatically fell,” Rocha told InSight Crime.

How the Pandemic Kick-Started the Market

Then came the COVID-19 pandemic. Brazil was first hit in February 2020, when car thefts had bottomed out. Supply chains halted, and imports of cars and parts dropped. New cars became scarce, so the demand for used vehicles shot up – as did prices. With rising demand, the sale of contraband car parts reemerged as a lucrative economy.

Vehicle thefts began to rise soon after COVID-19 hit Brazil

Number of vehicle thefts in São Paulo state, Brazil (Jan 2015-March 2024)

“There was a boom in the used car market. And as soon as there’s a boom in the used car market, there’s also a boom in the used car parts market,” said Rocha. “Theft has increased because the car dealers want more parts.”

SEE ALSO: Firearms, Disappearances, Prison Overcrowding: Brazil’s Problems Are Getting Worse

The PCC likely spurred the 2020 rise in São Paulo, given its hegemony in the area plus its history with chop shops. An international cocaine trafficking juggernaut, the PCC also controls much of the local drug trade in the city of São Paulo. The PCC may now be leveraging that control to lure drug abusers into stealing cars on the group’s behalf.

“People who had never committed theft or robbery started stealing and robbing vehicles to take them to the chop shop because they knew they would get money to buy drugs,” Rocha told InSight Crime. “These are people…who weren’t criminals, but became addicted to drugs and ended up committing theft and robbery in order to get money.”

Car thefts have risen much faster than robberies, suggesting that elements of the chop shop law that previously deterred criminal groups from forcibly stealing cars may still be working. And in the first few months of 2024, thefts seemed to have leveled off.

“So far, the most relevant [factors influencing rates of vehicle thefts and robberies] are the chop shop law and shifts within the PCC,” Maldonado said.