Illegal mining is by far the most widespread and insidious environmental crime occurring in the Amazon’s tri-border regions.

In the early 1980s, prospectors began ravaging Amazon’s tri-border lands in search of gold. Since then, poor, desperate people and Indigenous communities have become a ready labor force for prospectors. They work for sophisticated and structured illegal mining operations that provide them digging and dredging machinery and pay them in small amounts of gold.

*This article is part of a joint investigation by InSight Crime and the Igarapé Institute on illegal mining, timber trafficking, and drug trafficking in the triple border areas between Colombia, Peru, Brazil, and Venezuela. Read the other chapters here or download the full PDF.

On the Colombian and Venezuelan sides, mining activities and businesses that have sprung up around the sites are taxed by criminals, ranging from a few gunmen to factions of Non-State Armed Groups (NSAGs). The latter include the ex-FARC, made up of dissident groups of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia – FARC), which demobilized in 2017, and units from Colombia’s last remaining guerrilla force, the National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional – ELN). Brazil’s most powerful mafia, the First Capital Command (Primeiro Comando da Capital – PCC), also appears to be making inroads into the illegal gold trade.

SEE ALSO: Beneath The Surface of Illegal Gold Mining in the Amazon

An extensive entrepreneurial criminal network launders the gold. Using fleets of small planes, air transport companies shuttle supplies in and gold out. In Brazil, owners of these firms have come under investigation for actively facilitating illegal mining and laundering gold.

In Colombia and Brazil, traders openly buy illegal gold, from individual prospectors up to owners of mining operations. Businessmen with webs of companies profit up and down the illegal gold chain.

When the gold is ultimately smelted, its illegal origins melt away.

Dredging Rafts Invade Colombia’s Rivers

The densely forested banks of the rivers that cut through Brazil and Colombia echo with the rumble of “dragons,” huge dredging rafts that suck up riverbeds through industrial hoses to capture gold particles.

Brazilian miners motor around freely in this remote Amazon region. According to a Colombian military official, the dredging rafts are mostly constructed on the Brazil side of the border, where they operate largely unchecked.

Along a bend in the Puré River, which runs from Colombia into Brazil, the roof of one dragon is easily spotted in an aerial photo. So are the effects of its constant dredging. On one side of the raft, the river is glassy. On the other, it is turbid. What cannot be seen are the effects of the poisonous mercury, used to separate gold, that has washed back into this environment.

Gold dredging rafts first invaded Colombia’s Amazon in the early 2000s, when they were seen along the Caquetá River, which becomes the Japurá River in Brazil. A decade later, their reach had extended well down the Putumayo River, further south.

In recent years, dredges manned by illegal miners have ramped up operations in this Amazon border region, particularly in Tarapacá. The Colombian region, which abuts Peru and Brazil, has become a gold mining hotspot thanks to the many rivers running through it. The Putumayo River crosses Tarapacá’s southern edge, while the Cotuhé River intersects with the Putumayo there. At Tarapacá’s northeastern corner, the Puré River passes from Colombia into Brazil.

The Puré River had the highest incidence of illegal gold mining out of ten rivers analyzed in 2021 by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and Colombia’s Ministry of Mines and Energy (Ministerio de Ministerio de Minas y Energia). Portions of the Putumayo and Cotuhé rivers in Tarapacá also showed considerable activity last year, according to the UNODC report.

The illegal dredging rafts from Brazil took advantage of reduced military patrols during the COVID-19 pandemic to make incursions into the region, according to government officials and Indigenous activists working in Colombia’s Amazonas department. Jhon Fredy Valencia, agricultural and environmental secretary for the Amazonas department, said illegal mining has increased markedly over the last few years.

Valencia and the Colombian military official explained that tackling illegal mining in the tri-border is extremely difficult. To get to the Puré River, for example, security officers have two options. The first is to cross the river on a tour that lasts six days from Leticia. This includes entering Brazilian territory, which due to territorial sovereignty issues requires high-level coordination between the military and the foreign ministry of both countries. The other option is to arrive by helicopter, but this alerts the miners and truncates the effectiveness of the operations.

“The miners work with rafts that move easily through the rivers and, when military operations are carried out in one place, they simply cross the border,” Valencia said.

From Dredging Rafts to Dragons

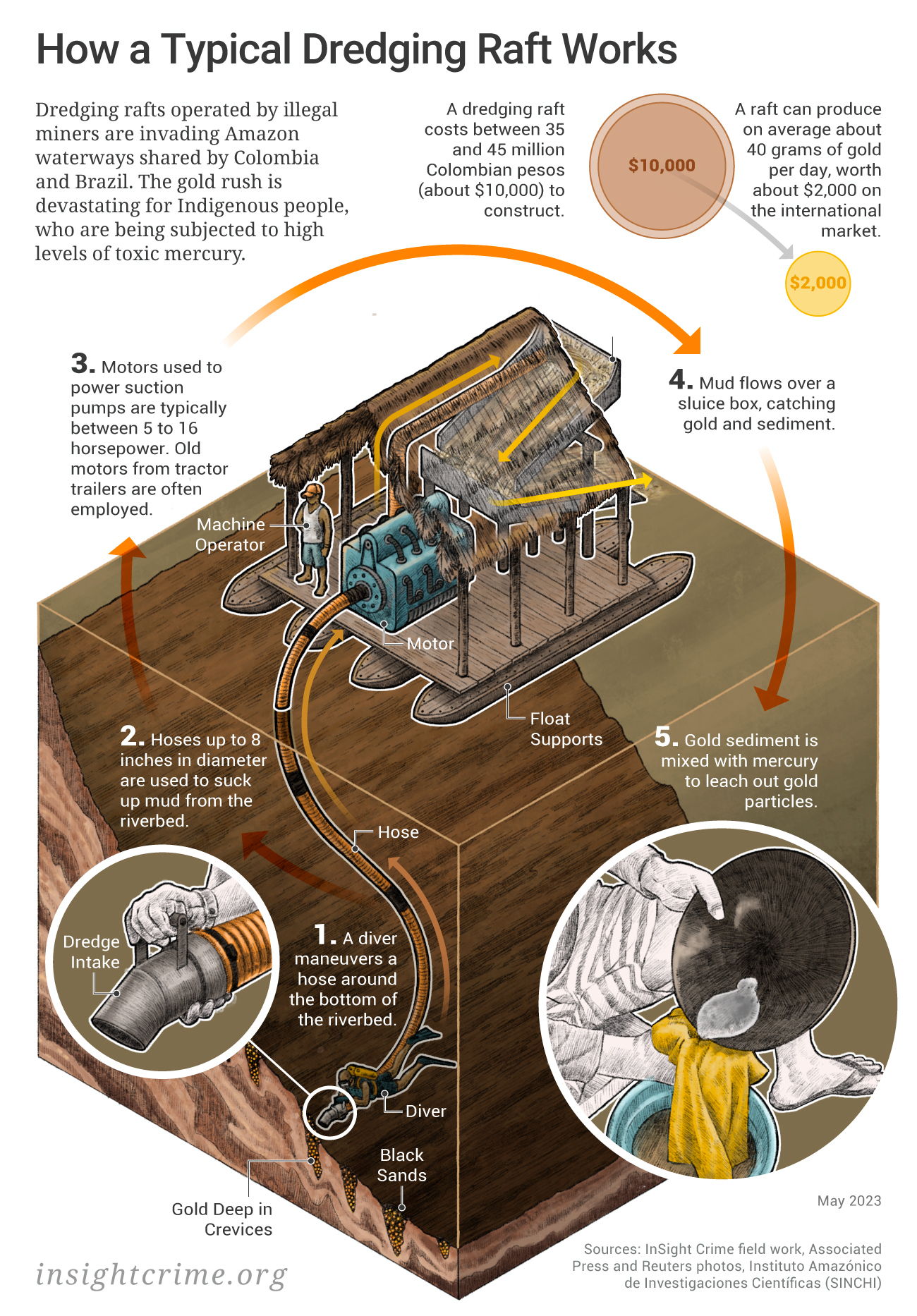

Most dredging rafts are constructed atop planks or logs. Each holds a gas motor, sometimes from an old tractor trailer, and a hose some 8 inches in diameter, or about the size of a soccer ball. The hose sucks up mud from the riverbed. The drawn-up mud is then pushed toward a sluice, which collects sediment and gold particles as the slurry runs back into the river.

The rafts cost between $8,000 to $10,000 to construct and can produce up to 40 grams of gold per day. That amount can be sold locally for $400 to $600, and is worth up to $2,000 on the international market. This type of river mining, though, cannot be conducted year-round due to changing water levels.

The so-called dragons are the largest type of raft. They often have multiple stories and carry equipment that is vastly larger, heavier, and more expensive than the small rafts’ gear. These include motors of 60 horsepower and multiple hoses with diameters up to 15 inches. The biggest dragons, constructed of both wood and metal to handle such equipment, cost some $45,000 to build, according to multiple law enforcement sources.

Brazilians appear to be the main operators of the rafts. Antonio Torres, Brazil’s diplomatic consul in Leticia, said in August 2022 that three Brazilian nationals, two men and a woman, were jailed on charges of illegal mining. In a September 2022 operation on the Pureté river, Colombian authorities arrested six Brazilian nationals.

Colombians are involved as well. For example, a 2020 interdiction of ten dredging rafts on the Puré river led to the arrest of three people, two Brazilian nationals and a Colombian.

Brazil took little action against illegal mining during Jair Bolsonaro’s tenure (2019-2022). While Brazilian authorities did destroy some heavy machinery, their efforts paled in comparison to the environmental havoc caused by illegal miners, who Bolsonaro emboldened with his permissive extractive agenda. However, with former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva returning, Brazil’s stance against illegal mining has taken another turn. Since February 2023, Brazilian security forces have been carrying out operations to expel illegal miners from Yanomami lands and destroy their machinery.

SEE ALSO: Can Brazil Keep Illegal Miners Off Yanomami Lands?

Colombian authorities have had some success interdicting and destroying dredging rafts in the region. In 2021, they destroyed several illegal dredging rafts on the Puré, said José Reinaldo Mucca, director of Indigenous affairs in Colombia’s Amazonas department. In September 2022, the military interdicted and destroyed four dredging rafts on the Pureté River, which runs from Brazil into Colombia in the Tarapacá region.

The dragons, because of their size and their constant churning up of the riverbeds, are the easiest dredges to spot from the air. In their efforts to conceal them, illegal gold miners have painted roofs green and navigate them close to riverbanks. The operators have frequently sunk their own dredges to avoid interdiction efforts.

However, the Colombian government does not have adequate resources for constant patrols and law enforcement, or to man military outposts in the jungle. Miners have thwarted aerial surveillance and interdiction attempts by monitoring the operations and crossing into Brazil or Peru when they detect Colombian authorities. This, coupled with geographical difficulties and coordination challenges between the three countries, makes stopping illegal mining a daunting task.

Illegal Mining Attracts Spate of Criminal Actors

Given the cost of constructing the rafts, the miners themselves are likely receiving backing from illegal gold financiers in either Brazil or Colombia. A single raft can accumulate over 14 kilograms (494 ounces) of gold a year, which can be sold for between $150,000 and $200,000 locally and is worth about $877,000, based on the international price of an ounce of gold in 2022.

Gold is processed weekly on the rivers and moved to Brazil. Once there, it is easily mixed with gold from other sources and then laundered. Colombian buyers also purchase nuggets directly from the rafts and move the gold through Colombian markets.

In Colombia’s Amazonas department, illegal mining appears to be partly controlled by armed groups. In Tarapacá, a group known as Los Comandos de la Frontera, or Border Command (to be discussed in the drug trafficking section of this report) exerts outsize influence and is likely overseeing illegal mining.

The human rights official who provides aid in Colombia’s Amazonas department said that the Border Command profits not only from drug trafficking but also illegal mining. Mucca, the Indigenous affairs official, agreed that the group is likely involved in both activities. The six Brazilians arrested on the Pureté in September 2022 were in “service” of the Border Command, Gen. Jaime Galindo, the commander of the Army’s Sixth Division, told the media.

“From the Cotuhé and above, it’s a mafia,” Mucca said.

Effects of Illegal Mining on Indigenous Communities

Indigenous communities, who are the first line of defense against illegal mining preying on the Amazon, have become the target of threats and attacks from mining networks.

The presence of mining actors in their territories has left Indigenous communities with no choice but to comply with mining operations. This generates all types of difficulties for the communities, including violence, said a representative of the National Organization of Indigenous peoples of the Colombian Amazon (Organización Nacional de los Pueblos Indígenas de la Amazonía Colombiana – OPIAC).

“In some mining sectors we have allegations about the killing of Indigenous leaders, and disappearances of some leaders,” he said.

The few economic opportunities at the tri-borders mean some local communities have struggled to resist the incursions of illegal mining. Youths are often employed as divers who move hoses around riverbeds. Women serve as cooks, and men as mining operators. They are paid in cash or in coupons that can be used to redeem items from certain stores in Tarapacá.

Indigenous leaders, or caciques, in some of Colombian Amazonas’ communities have made deals with prospectors, according to Mucca, the Indigenous affairs official. In Tarapacá, for example, some Indigenous elders were paid 3 million pesos (about $680) for allowing illegal mining rafts to pour into their waterways.

Mining is often conducted by illegal groups backed by patrones, or bosses, who have the financial capacity to bring expensive equipment to these territories, said the representative of the OPIAC.

Illegal Mining has also brought health hazards. Gold-containing sediment is mixed with mercury to extract the gold, usually close to waterways or even on the rafts themselves. Some of the leftover mercury gets washed back into the waterways.

According to a 2018 study of mercury contamination in Colombia’s Amazon, high levels were discovered in hair samples of people in Tarapacá’s Indigenous communities. Of the nine communities tested, all were at least double the threshold considered safe by the World Health Organization (a daily intake of 1.6 parts per million), and four had levels at least seven times above that limit. Today’s levels are almost certain to be higher.

Mercury poisoning can impair children’s development, damaging the brain and other parts of the nervous system. Mercury can also be toxic to adults, causing brain and kidney damage, blindness, and heart disease.

Government, health, and justice officials have held meetings with Indigenous communities to discuss issues of mercury, according to Valencia, the Colombian Amazonas government official.

“It’s not only an issue of going to them and saying there is a problem,” he said. “We also need to provide them with solutions,” including medical attention for those affected.

Gold and Guerillas: Venezuela’s Yapacana National Park

Mud pits mark illegal gold mining sites in Venezuela’s Yapacana National Park, home to towering flat-topped mountains and plunging waterfalls. Inside a moon-like crater, dead trees are scattered like twigs, a video shows.

Yapacana National Park sits in southwest Venezuela, near the Colombia border. According to a 2019 report by SOS Orinoco, mining operations in the reserve increased from about 220 hectares in 2010 to more than 2,000 hectares in 2018, equal to about 1,500 soccer fields. The following year, mining operations destroyed an additional 200 hectares, and sites jumped from 36 in 2018 to 69 in 2019, according to the organization.

Venezuela has the second-highest number of illegal mines among the Amazon countries, surpassed only by the much larger country of Brazil. Of 4,472 illegal mining sites throughout the region, at least 1,423 are in the Venezuelan Amazon, according to the Amazon Network of Georeferenced Socio-Environmental Information (Red Amazónica de Información Socioambiental Georreferenciada – RAISG). And Yapacana is the largest and least regulated mining area” in its entire Orinoco-Amazon region, stated SOS Orinoco, the illegal mining watchdog group.

The spreading mines have left denuded lands across the park, which is larger than the country of Luxembourg.

Venezuelan journalist and political activist Luis Alejandro Acosta, who is based in Venezuela’s Amazonas state and has traveled to Cerro Yapacana, said sites can have up to 10 backhoes working on them at once.

“Production there never stops,” he said. “Day and night.”

A Gold Mine for the Ex-FARC Mafia

Venezuela President Nicolás Maduro has turned to the sale of illegal gold to prop up his regime in the face of sanctions and massive declines in oil wealth.

Colombian guerrillas oversee much of the gold rush across Yapacana National Park. Maduro’s predecessor, the late Hugo Chávez, first ceded the park to FARC rebels in the early 2000s, according to Acosta.

Chávez granted the guerillas sanctuary along much of the border region. He saw the rebel force as a strategic tool in the wake of a United States-supported coup in April 2002, which briefly toppled him from power. Granting the FARC safe haven also served as a bulwark against an increasingly hostile Colombia, the region’s key US ally.

Today, Venezuela is not only a refuge for guerrillas. The ex-FARC have spread deep into Venezuelan territory, taking control of communities and criminal economies. And what used to be a Colombian guerrilla is today a binational group.

Back in the early 2000s, the tri-border provided critical drug smuggling opportunities for the FARC’s Eastern Bloc and its 16th Front. Up to 20 tons of cocaine a month were exported by the 16th Front to Brazilian drug trafficker Luiz Fernando da Costa, alias “Fernandinho Beira-Mar,” or “Fredy Seashore.” FARC commander Géner García Molina, alias “Jhon 40,” controlled drug smuggling in the region, handling up to 100 tons of cocaine per year while developing a penchant for horses and Rolex watches.

At that time, the FARC paid little attention to the gold in Yapacana, though illegal mining had been occurring sporadically there since the 1980s. According to Acosta, the guerrillas only began to extort miners as a revenue ploy in about 2010.

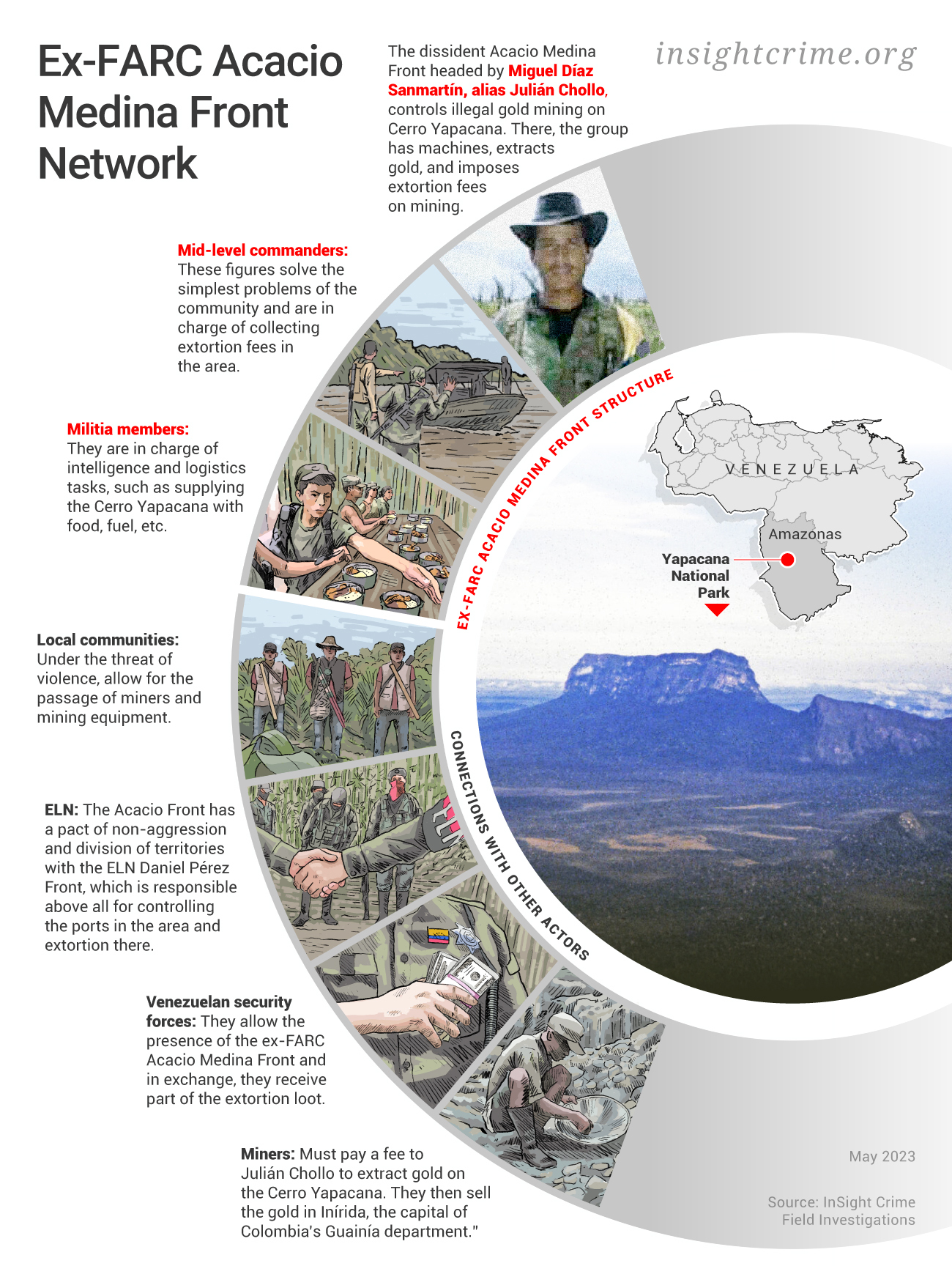

When the FARC came to a peace agreement in 2016, Jhon 40 and Miguel Díaz Sanmartín, alias “Julián Chollo,” were among the first rebels who refused to surrender. Instead, they formed the ex-FARC’s Acacio Medina Front — composed of former members of the 16th Front — in the border area where Colombia’s Guainía department and Venezuela’s Amazonas state meet.

Julián Chollo — described as a “lone wolf” who joined the FARC at the age of 20 — now controls the Yapacana region, widely taxing employees of illegal mining operations.

Tens of thousands of miners have flocked to Yapacana to dig for gold. About 25,000 people are present there daily, though not all of them are miners. Some work in the camps as cooks, drivers, and vendors, Acosta said.

Chollo charges them precise fees: 5 grams of gold for each backhoe in operation, 3 grams to maintain a business, 1 gram per boat bringing in miners and supplies, and so on.

“That is a lot of gold collected every 15 days,” Acosta said. Meanwhile, the largest mines and machines, “those that extract the most gold,” belong to the guerrillas, he added.

An Indigenous community leader from the region who asked to speak anonymously out of fear of reprisals agreed that the ex-FARC have total command of Yapacana. Elders have made deals with the guerrillas, receiving motors, farming tools, and other items from them in exchange for control of their territories, the community leader said.

For some of the Indigenous, Chollo is like “a Robin Hood,” the Indigenous leader said. “If there is someone who wants to buy an iron, he gives it to them. And with that, the community has been bought off,” he said.

Communities also face menacing violence.

“They invade our spaces by threatening us,” said another Indigenous leader who also asked for anonymity. “We are submissive to them, and they are the ones who rule, who set the laws.”

Mining Supply Lines Taxed by ELN

The Orinoco River and its tributaries serve as throughways to Yapacana. About 75 kilometers upriver on the Orinoco sits San Fernando de Atabapo, a Venezuelan border town where gold is the principal currency. Food and alcohol are bought with “rayas,” or “lines,” which are small amounts of gold worth about $3. Gold is also bartered for larger items, such as appliances.

Colombia’s river town of Inírida, about 25 kilometers west of San Fernado de Atabapo on the Guaviare, serves as a transport hub. From there, large raft boats begin a two-day journey to Yapacana, carrying machinery, fuel, and other supplies. To haul 20 tons costs about $1,000, Acosta said.

Units from Colombia’s ELN guerrilla force charge fees for boats to pass. More than 50 such control points exist, according to an Indigenous community member.

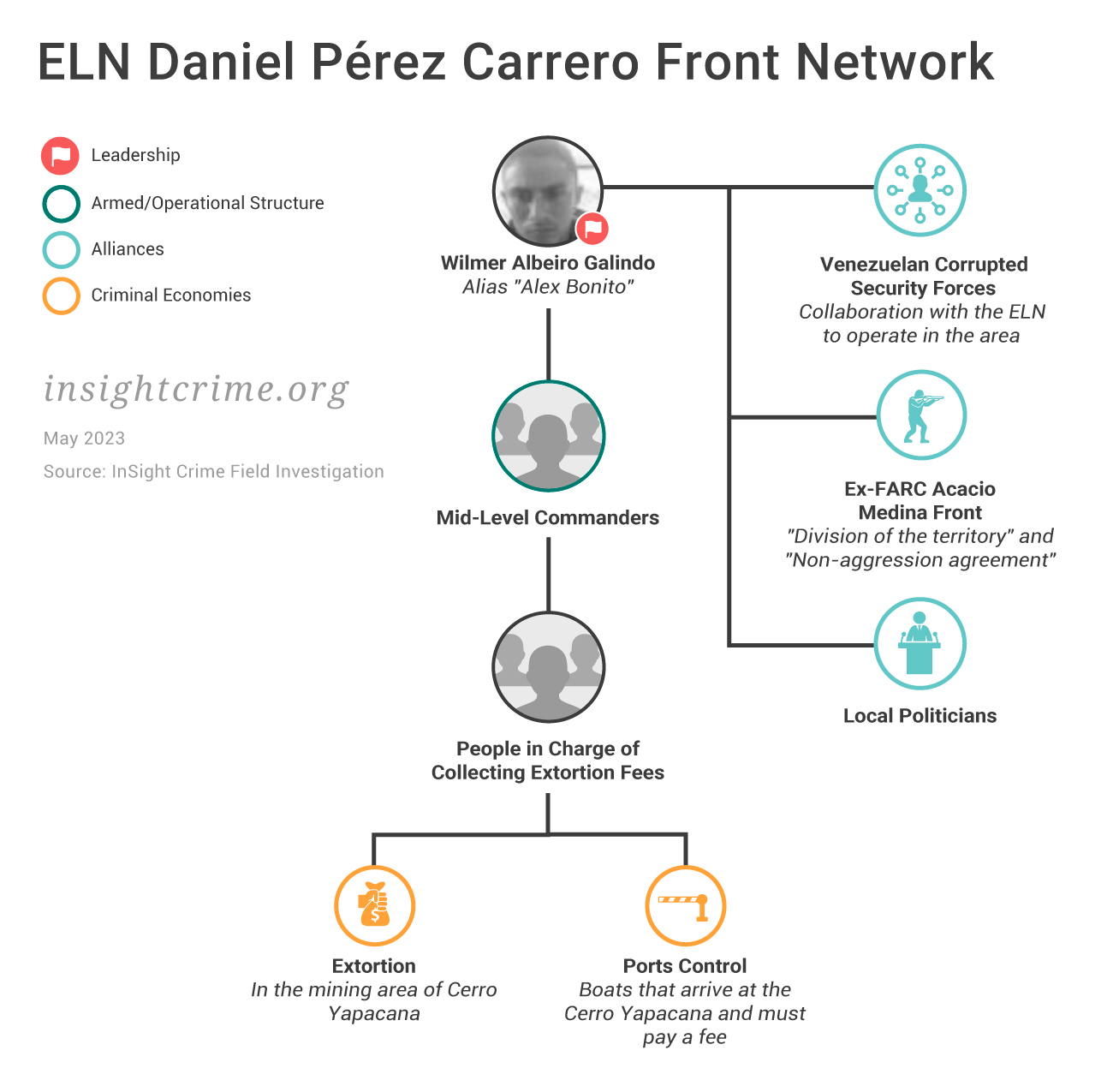

Pushing south from the Venezuelan state of Apure into Amazonas, ELN fighters have waged a campaign along the Orinoco River. The 2017 demobilization of the FARC, through a historic agreement with Colombia’s government the year before, cleared the way for the ELN’s Daniel Pérez Front to move into the region.

Wilmer Albeiro Galindo, alias “Alex Bonito,” heads the guerilla unit, which carried out a wave of killings when it arrived in 2020. Members of the ELN and ex-FARC initially clashed. But the two groups have managed to delineate space and share an uneasy alliance.

“They coexist, share, coordinate. I don’t know how,” said an official for an Indigenous community organization who asked to speak anonymously for security reasons. “Along the border, the ELN is more visible. They are along the Inírida River, where they extort and conduct illegal mining. Meanwhile the FARC does the same, but in Cerro Yapacana.”

Illegal Gold Rush Draws Criminal Groups to Brazil’s Yanomami Reserve

On October 2nd, the owner of a trade tent on Brazil’s Uraricoera River received a WhatsApp message from the “wolves,” an armed gang of illegal prospectors. An attack was coming, he urgently warned a group of Yanomami Indigenous gathered there.

Before the Yanomami could flee, gunmen arrived in two boats and opened fire. A 15-year-old Yanomami boy was shot in the face. A bullet, photos show, hit him in the left cheek and then exited the back of his neck. Miraculously, the boy survived.

A 46-year-old Yanomami man named Cleomar was not so lucky. He was killed when shots struck him in the forehead and chest as he flung himself into the river attempting to escape, according to a letter sent to Brazilian authorities by the Hutukara Yanomami Association (Hutukara Associação Yanomami), which represents the Yanomami people in Brazil.

“What happened demonstrates that the situation of insecurity on the Uraricoera River, due to the unimpeded circulation of illegal miners, has not ceased and deserves urgent intervention,” Yanomami leader Dário Kopenawa wrote in a letter signed October 4, 2022.

Some 20,000 illegal prospectors have pushed into the Yanomami reserve, felling trees and ripping up riverbeds. Greater in size than Portugal, the reserve stretches across over 105,000 square kilometers on the Brazil-Venezuela border, making it the world’s largest Indigenous territory.

The Uraricoera River, which cuts across the northern section of the reserve, acts as highway for the advance of criminal mining operations there. Vessels ranging from long wooden boats to massive dredges motor along the waterway, carrying a constant influx of miners, supplies, equipment, food, alcohol, and fuel.

Armed men who patrol the Uraricoera in speedboats offer some of the most visible proof of organized crime’s spread into illegal gold mining. The gangs tax miners and others along the river, including boatmen and shopkeepers. Drug trafficking and brothels bring the gangs further earnings.

Some of the gunmen are themselves part of mining operations. Others are alleged to be part of Brazil’s largest and most powerful criminal gang, the First Capital Command (Primeiro Comando da Capital – PCC), which appears to be taking on a greater role in illegal mining in the Yanomami reserve.

Corrupt authorities are also involved. Members of an elite regional intelligence unit have been implicated in providing weapons and having links to a man nicknamed “Soldado,” who is described in a police investigation as a head of “mining security” on the Uraricoera.

Members of the army operating in Roraima, one of the states that the Yanomami reserve crosses, have been accused of leaking information on operations against illegal mining and receiving bribes in exchange for turning a blind eye to the movement of drugs and gold, according to Brazilian media coverage of intelligence reports from the government’s Indigenous affairs agency (Fundação Nacional dos Povos Indígenas – Funai).

Kopenawa, the Yanomami leader, wrote in his letter that “there are constant fears about the amount of heavily armed prospectors coming up and down” the river.

Wildcat Miners Lay Waste to the Forest

Intrusions by illegal miners, known in Brazil as garimpeiros, began in the 1980s. A decade later, amid international pressure, the Brazilian government suffocated most illegal mining in the region. History repeated itself and illegal mining rekindled in the Yanomami reserve during the tenure of former President Jair Bolsonaro, who vowed to develop the Amazon economically and tap its mineral riches.

According to a report by the Hutukara Yanomami Association and the Social-Environmental Institute civil society organization (Instituto Socioambiental – ISA), an environmental and Indigenous rights advocacy group, deforestation in the reserve more than doubled from some 1,200 hectares in 2018 to 3,300 (equal to about 2,400 soccer fields), by the end of 2021. All of it related to mining. More than half of the gold mining on the reserve takes place around the Uraricoera River.

The zone within the reserve that has seen the worst deforestation during the past two years is Waikás, located on the Uraricoera in the northern part of Roraima. In 2020 and 2021, nearly 2,600 hectares of forest were destroyed there by miners who travel the river unchallenged.

Mining operations have also begun in the Auaris region, in the northwest corner of the reserve, which borders Venezuela. Two mining sites have been observed there using satellite imagery, according to the report by the Hutukara Yanomami Association and the Social-Environmental Institute. One sits on the Brazilian side of the border, and the other on the Venezuelan side. Both sites are small but appear to be growing.

Illegal prospectors looking for gold have overrun other rivers as well. Mining near the Parima River intensified during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, stripping more than 100 hectares of forest. Deforested land around Xitei, at the headwaters of the Parima, jumped from 11 hectares in 2020 to 136 in 2021, the largest increase of any region tracked by the report.

The Mucujaí River, which runs east across the reserve to the Mucujaí municipality in Roraima, and its surrounding forests have been devastated by illegal mining operations. In Homoxi, a region at the headwaters of the Mucujaí, a chain of massive mining pits appears like a small a town carved into the greenery, an aerial photo shows. In March 2022, one pit swallowed a medical post serving the Yanomami community.

A video taken by miners, circulated by local news media in April 2021, shows them bragging about having altered the course of the Mucujaí. A miner films the silt-choked river, saying, “look at how we left it.” He then pans over to show a pump and large hoses. “We now are working on the riverbed,” he says.

SEE ALSO: Brazil’s PCC Complicates Fight Against Illegal Mining in Amazon

This type of wildcat mining lays waste to the rainforest. Trees are razed to dig pits. Powerful streams of water are shot into them to loosen the earth. Gas-powered pumps suck up the mud, which is then washed over a long sluice. The extracted sediment is mixed with liquid mercury, which clings to the gold. Using shallow pans, the miners then heat the resulting amalgam to form nuggets.

The process poisons the forest. Trees absorb mercury vapor, while milky, mercury-contaminated toxic pools are left behind to leach into groundwater and rivers.

The widespread use of mercury threatens the Yanomami, who live in large, circular communal dwellings that house as many as 400 people. As with the exposed Indigenous communities in Colombia, high concentrations of mercury were found in hair samples from Yanomami communities near mining sites. An analysis of water at the confluence of the Orinoco and Ventuari rivers, at the western edge of Yapacana national park, found high levels of mercury as well.

Fish, a major part of the diet of the Yanomami, are contaminated. According to a 2022 study, more than half the fish collected from the Mucujaí and Uraricoera rivers have mercury levels considered unsafe for consumption. Prolonged exposure to mercury causes fatigue, and damage to the immune system and vital organs.

Júnior Kekurari, a Yanomami leader who heads the local Indigenous health council, has described miners working within 50 to 200 meters from Yanomami communities.

“The Yanomami land, since 2018, has suffered a lot … Rivers are destroyed, there is only mud, contaminated with mercury, the smell of gasoline … Children play in the river, drink. The community consumes water that is dirty,” Kekurari explained in an interview with the podcast Ao Ponto, from the newspaper O Globo.

Garimpeiros and Gunmen Find Golden Opportunity

Strictly speaking, garimpeiro refers to small-scale artisanal miners, though the term is outdated. Most garimpo operations are no longer artisanal, since they use heavy machinery, including rafts, dredges, tractors, and bulldozers. And the term today is more commonly used to refer to illegal miners in the Amazon.

Of 174 tons of gold traded between 2019 and 2020, garimpeiros are estimated to be responsible for 49 tons, equivalent to 28% of Brazil’s gold production.

Brazilian law allows them to operate legally, including in parts of the Amazon. Under ordinance DNPM 155, enacted in 2016, each garimpeiro is allowed to mine in up to 50 hectares in designated areas, while mining cooperatives may be granted up to 10,000 hectares. Brazilian law restricts garimpo in Indigenous Lands and environmental protected areas.

The law, however, puts no restrictions on techniques or equipment, unlike neighbors Colombia and Peru. Colombian law requires strict registration of machinery through the Ministry of Transportation, while Peru has banned the use of heavy machinery in small-scale mining, among other measures.

Miners have rapidly expanded outside of permitted areas and invaded protected regions, clambering to get at gold using everything from pickaxes and chainsaws to heavy machinery that includes backhoes. Illegal mining operations on Indigenous lands jumped nearly 500% from 2010 to 2020, according to a study by MapBiomas, which tracks land transformation in Brazil. In conservation areas, the increase was just over 300%.

Most miners come from rural communities with poor educational systems and limited opportunities for well-paid work. Individual miners are often co-opted by criminal entities that supply them machinery in exchange for most of their returns.

The miners move fluidly among the three countries of this border region. For example, Brazilian garimpeiros have ventured into the portion of the Yanomami located in the Venezuelan side to set up mines. According to an investigation by news outlet UOL that used video, photos, documents, and interviews with Indigenous leaders, the number of miners crossing the border number anywhere between 500 and 5,000.

Garimpeiros and other types of laborers, hailing from other regions of Brazil, are drawn to Yanomami territory by ads on social media offering a range of jobs, including as machine operators, drivers, pilots, and cooks.

As in Venezuela’s Yapacana, the currency in the Yanomami reserve is gold. Boatmen who shuttle miners on long, difficult-to-navigate stretches of the Uraricoera earn 10 grams per passenger. Bars, brothels, and canteens have sprung up along the river and around mining sites.

In Brazil, mine “owners” control all commercial, logistical, and camping structures on the Uraricoera River.One example of a so-called mine owner is Dona Iris, who was arrested in June 2022 on illegal weapons charges. An arrest affidavit reported by O Globo alleges that the 55-year-old woman used properties in Alto Alegre, a municipality in northeastern Roraima, to shuttle supplies and people to illegal mining sites, where she employed an armed escort. According to the report by Hutukara Yanomami Association and the ISA, Dona Iris ordered attacks on riverside Yanomami villages in retaliation for blocking mining operations.

Mine owners charge fees for access to makeshift ports. They extort miners and tax the sale of alcohol and other products. Prostitution and drug sales are also under their control. Venezuelan women traveling across the border have been lured to mining sites and sexually exploited. One woman who spoke with Brazil news outlet Folha de S. Paulo said she was trafficked by a madame who convinced her to go to a mining site, where she was raped.

Booming illegal commerce has drawn more dangerous criminal actors to the region and opened a path for them to enter the illicit gold trade. A video recorded in 2021 showed an armed gang on an aluminum motorboat speeding along the Uraricoera River. In this video, the men, some of them hooded, brandish pistols and shotguns. The camera then turns to a man in a red T-shirt and baseball cap, with a thick gold chain hanging from his neck that ends in a crown pendant.

“Look at us, look at us, look at us. These damn Indians think they are in charge. We are in charge. We’re the fucking boss. Today we are going to see how this shit works. Look. Look. Look. We are the war.”

One of the men in the boat later arrested was found to be a fugitive linked to the PCC gang. Charged with drug trafficking in 2013, Janderson Edmilson Cavalcante Alves had escaped from a Roraima prison and fled to Venezuela, where he was later linked to a 2019 robbery of 100 rifles at an army barracks.

To escape authorities in Venezuela, the 30-year-old holed up in the Brazil border region, where he trafficked drugs and served as a hired gun for mining operations. The arrest of Cavalcante Alves, who told authorities he was an associate of the PCC, provides a glimpse of the criminal gang’s presence in illegal mining on Yanomami territory.

Roney Cruz, head of an intelligence division of Roraima’s prison system (Divisão de Inteligência e Captura do Sistema Prisional de Roraima), has told local news outlets that PCC gang members are active in the mines. In an investigation by Brazilian news outlet UOL, Cruz said the gang even had a boat moored in the Uraricoera that they called the funerária, or funeral home, for its use in death missions.

It makes sense that the PCC would have a toehold in the mines in some way, given the sheer amount of criminal activity occurring there and the group’s growing strength in Roraima and the rest of Brazil’s Amazon region.

The UOL investigation goes further, claiming that gang leader Endson da Silva Oliveira, alias “Bebezão,” and his brother, Emerson, structured PCC activities along the Uraricoera. Killed in separate shootings, the brothers had an accomplice who was found with mining equipment in his home.

It’s unclear, though, whether the PCC merely has a few members who have found opportunity acting as enforcers in the lawless mines, or if gang members have infiltrated the higher ranks of mining operations as well.

What is clear is that criminals have acted with impunity in Yanomami territory for years in the absence of authorities. Despite being the Indigenous territory with the largest number of federal police operations, these have been largely ineffective. The police assure that many operations have not taken place due to a lack of logistical support from the army and other federal institutions. Another government security post, known as Ethno-Environmental Protection Bases (Base de Proteção Etnoambiental – Bape), that controlled access to the Uraricoera River has been inactive for several years.

Some Yanomami have sought to protect themselves from the encroachment of illegal miners.

In 2021, Yanomami in Palimiú put up a barricade in the Uraricoera and stopped a speedboat full of miners. Yanomami youth carried away some 1,000 liters of fuel before turning the boat around. Their actions were in retaliation for the drowning of a child knocked over by a mining boat’s wake, according to the report by Hutukara Yanomami Association and the ISA.

For several months afterward, gunmen in motorboats drove past Palimú’s riverside villages, firing shots from automatic weapons. The threat of violence against them continues.

In his October 2022 letter to authorities, Yanomami leader Kopenawa said that a miner known as “Brabo” had recently warned the community in Palimiú to “not oppose illegal mining installed in the region — if they did not want a repeat of the episodes of attacks in 2021.”

Brazil Targets Illegal Gold Mining in Yanomami Lands

The impunity that illegal miners and criminal networks have enjoyed in Yanomami territory could be faltering. Brazil’s new president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, came to power with ambitions to reverse the destructive approach to the environment of his predecessor, Jair Bolsonaro.

During his first month in office, Lula visited Roraima state and the Yanomami territory.

“More than a humanitarian crisis, what I saw in Roraima was a genocide. A premeditated crime against the Yanomami, committed by a government impervious to the suffering of the Brazilian people,” Lula tweeted.

In January 2023, Lula’s justice minister, Flávio Dino, announced his intention to open an investigation with the federal police into the crimes that the Yanomami have suffered, including genocide.

SEE ALSO: Brazil Targets Illegal Gold Miners With Force and Legislation

At the same time, Lula deployed a crippling blow to illegal mining on Yanomami land. In February 2023, armed agents of the government’s environmental protection agency (Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais – Ibama), and the government’s Indigenous affairs agency (Fundação Nacional dos Povos Indígenas – Funai), launched an enforcement operation in the Yanomami reserve to expel thousands of wildcat gold miners. Helicopters, illegal airstrips, heavy machinery, fuel, and weapons have been destroyed.

The air force will control the airspace that until recently was unpatrolled. A mobile radar system will allow intercepting flights in the area, while the navy will patrol the rivers.

To avoid security operations, garimpeiros are crossing the borders into Venezuela and Guyana. And while this is a small victory for the defense of the Yanomami territory, it is also creating a balloon effect by displacing wildcat miners to other mining regions in the Amazon Basin.

Small Aircraft and Clandestine Airstrips Feed Illegal Mining in Brazil’s Amazon

It’s easy to detect the small planes and helicopters used in illegal mining operations. All seats but the pilot’s are stripped from the aircraft, replaced by metal and plywood shelving to hold gas containers. This fuel is flown to open pits to power motors, chainsaws, and digging machinery.

The fleets land on an expanding patchwork of airstrips near mining sites across the Brazilian Amazon. Most are little more than a path etched into the jungle. A few are pre-existing dirt runways, originally built to bring medicine and healthcare workers to Indigenous communities.

A New York Times investigation that examined thousands of satellite images dating back to 2016 found 1,269 unregistered airstrips in the Brazilian Amazon. Sixty-one of them occurred on Yanomami land.

These airstrips have been another gateway to the Yanomami reserve. Most flights take off from Boa Vista, Roraima’s capital, further east of the border between Brazil and Venezuela.

The Business of Illegal Gold in Brazil’s Boa Vista

Near Boa Vista, is the Barra do Vento airport, a primary transport hub for flights entering and exiting the Yanomami reserve.

Pilots arrive there in search of risky work that can bring big paydays in gold, according to the investigative news outlet Repórter Brasil. They fly small, old propeller planes low over the jungle canopy, navigating the maze of dirt landing strips. Some have crash-landed in the forest, never to be seen again.

Owners of air transport companies are among the major players alleged to be involved in illegal mining and laundering gold.

Two figures stand out as examples of this illicit nexus. Valdir José do Nascimento, known as Japão, is alleged to own a fleet of aircraft used to ferry food, fuel, and instruments to mining sites, and to shuttle gold out of them, according to Brazil’s Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office (Ministério Público Federal – MPF). In a single week, some 20 flights were carried out to mines by planes owned by Do Nascimento, Repórter Brasil reported. Each flight cost on average 10 to 12 grams of gold, prosecutors claimed.

Do Nascimento is the registered owner of seven 1970s-era single-engine Cessnas, as well as a twin-engine nine-seat plane. Prosecutors called him the “biggest promoter of illicit mining activity in the Yanomami Indigenous land,” according to Repórter Brasil.

Pilot and aviation businessman Rodrigo Martins de Mello has also come under investigation for his involvement in illegal mining. He was charged in December 2022 with extraction of minerals without authorization and formation of a criminal organization, as well as other crimes, according to a complaint filed in federal court.

Martins de Mello, who ran for congress under Bolsonaro’s Liberal Party (PL) in the 2022 election and is an outspoken supporter of mining interests, had helicopters seized during a 2021 raid of his air taxi company and drilling firm based near Boa Vista. Both businesses are the subject of a police probe into a larger illegal mining network that moved more than 200 million reais (about $37.5 million) over two years, according to prosecutors.

Martins de Mello has denied allegations of involvement in illegal mining, saying that “there is a lot of fanciful information.”

Despite wrapping himself in the flag at campaign rallies, Martins de Mello, who is also known locally as Rodrigo Cataratas, lost his bid for congress. Even after his defeat, which came as a relief to Indigenous rights activists who feared his election would grant him immunity from prosecution, Martins de Mello continued to rally for gold mining interests.

In an interview with Folha de S. Paulo, Martins de Mello promised to “carry the message of the need to resolve this conflict between gold miners and federal agencies,” and characterized the miners as “victims of abuse of authority by federal agencies.”

About a month after the October election, a federal court ordered the arrest of Martins de Mello’s son, Celso Rodrigo de Mello. The warrant alleged Celso Rodrigo’s involvement in suspicious transactions and a helicopter crash that killed two people.

The Links in Gold Laundering Networks

Downtown Boa Vista is home to the “Rua do Ouro,” or “Street of Gold,” where dozens of small jewelry shops and distributors of securities, or DTVMs (Distribuidora de Títulos e Valores mobiliários), openly purchase illegal gold extracted in Yanomami lands and other parts of the Amazon. Doors are tinted. Men guard entrances. Most stores lack display windows. According to Amazonia Real reporters who visited Rua do Ouro and spoke to a goldsmith there, gold is sold as sediment or nuggets to be further refined.

Prospectors, drivers, cooks, and anyone else with gold to sell make use of the shops. Pilots deliver them large quantities of gold on behalf of illegal mine operators.

The shops serve as the first link in the gold laundering chain. The gold, though, must be moved elsewhere in the country for export. According to Brazil’s National Mining Agency (Agência Nacional de Mineração – ANM), the body responsible for granting and monitoring licenses for miners, there are no legal mining operations whatsoever in Roraima.

The mixing of illegal and legal gold for export is often done by networks affiliated with designated brokers and DTVMs, which are the entities authorized by the Central Bank to buy and sell gold in Brazil.

According to an Escolhas Institute study, which has investigated the companies involved in the laundering of illegal gold in Brazil, Brazil’s four largest DTVMs traded some 90 tons of gold, about a fifth of the country’s production, from 2015 to 2020. The vast majority of this — some 79 tons (worth about $3.8 billion at that time) — were of suspect origin.

Some of the largest DTVMs often control the entire gold chain, starting with mining titles and permits. DTVM associate companies include those involved in geological surveys, extraction, gold buyers in various states, and refining.

So far, the DTVMs can easily avoid accountability when purchasing gold. Enacted in 2013, Law No. 12,844 — which regulates the purchase, sale, and transport of gold — requires sellers, not buyers, to prove the gold is of legal origin. Sellers self-declare sources of their gold, providing copies of mining permit numbers, said Larissa Rodrigues of Brazil’s Escolhas Institute, which has investigated the companies involved in the laundering of illegal gold in Brazil.

The reality is that anyone can say “gold came from this area, with mining permit X, and no one will check,” Rodrigues said. “The DTVMs or the shops will keep these forms, and it’s all considered to be done in good faith.”

In April 2023, however, the Brazilian Supreme Court challenged the “good faith” approach, granting an injunction to suspend the practice and mandating the establishment of a new regulatory policy. The decision reinforces the current government’s efforts to crack down on illegal gold mining in indigenous lands and other environmentally protected areas.

Heads of DTVMs, their family members, and associates have been alleged to be involved in illegal mining.

Brazil’s Federal Prosecutor’s Office has attempted to go after the DTVMs. In August 2021, prosecutors filed a civil suit against FD’Gold, Carol DTVM, and OM DTVM, three of the largest such firms, accusing them of pouring 4.3 tons of illegal gold into national and international markets over two years. The lawsuit calls for their operations to be suspended and the firms fined $10.6 billion reais (about $2 billion) for social and environmental damages.

One DTVM has been accused of orchestrating a vast network that laundered gold from Yanomami territory. The network came to light after a 2015 police raid that dismantled a mine of some 600 prospectors operating on the northern edge of the reserve. According to police and prosecutors, more than two dozen gold-buying storefronts in Boa Vista received the illegally produced ore, which was then refined and sent to 30 legitimate mining firms owned by the DTVM in the Amazonian cities of Manaus, in Amazonas; Itaituba and Santarém, in Pará; and Porto Velho, in Rondônia. Documents were forged to indicate that the gold came from legal mines in three states. The mining companies also further smelted the gold into 250-gram bars that were then sent to the DTVM.

Through the network, the DTVM received about two tons of gold per year, according to the head of a regional anti-organized crime unit who spoke to Amazonia Real. The accused DTVM, however, was never identified publicly.

Since Lula took office, he has launched a crusade to strengthen lax legislation that has facilitated gold laundering in Brazil. One of the first steps is the introduction of Resolution No. 129 of Brazil’s National Mining Agency (Agência Nacional de Mineração – ANM), the agency responsible for inspecting mining sites. With the implementation of this resolution, gold buyers must now have systems in place to prove that the gold they buy has not been illegally sourced.