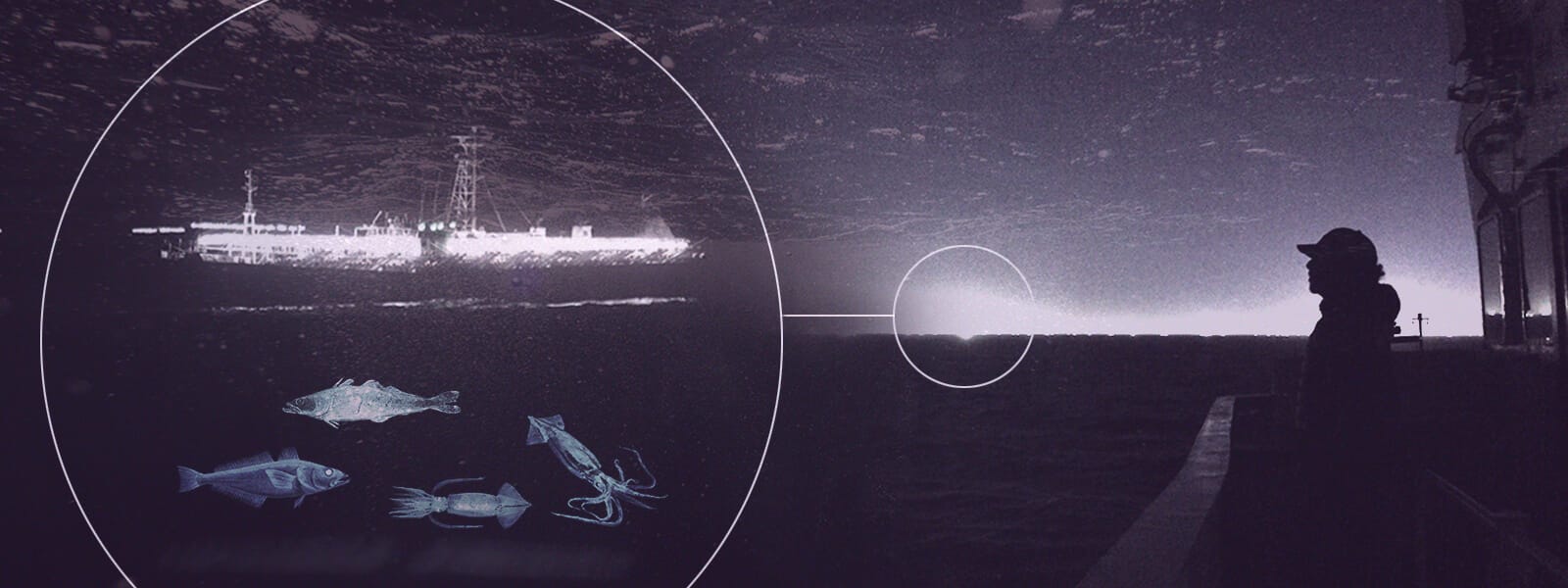

Every night from November to April, floodlights from hundreds of Chinese fishing boats illuminate the darkness some 200 miles off Argentina’s Atlantic Coast, where the armada harvests tons of squid.

“Many speak of a floating city, but because of the noise and the lights, I see it more as a set of vacuum cleaners within a giant machine,” an Argentine fisheries expert, who asked to remain anonymous because of his work in the sector, told InSight Crime.

Under international law, countries control the waters within 200 nautical miles of their shores. Argentina’s sea shelf – one of the widest in the world – runs to the edge of its ocean territory. This creates prodigious fishing grounds just where Argentina’s maritime law ends.

“Beyond mile 200, there is no control, and they fish what they can day and night,” said Daniel Coluccio, director of Argentina Maritime Naval Observatory, which is dedicated to monitoring fishing in the southern Atlantic.*

“At some point the resource is going to diminish,” he told InSight Crime.

Nautical Mile 201: Where the Law Ends

For Coluccio, the problems start at nautical mile 201 in the Atlantic between the southern latitudes of 42 and 50 degrees, at the southern end of the country.

The extensive sea shelf provides fertile feeding grounds for marine life, thanks to nutrient-rich currents that produce massive amounts of plankton. Southern cod, also known as merluza negra, lobster, squid, and other valuable species thrive there.

SEE ALSO: Plundered Oceans: IUU Fishing in Central American and Caribbean Waters

At a relatively shallow depth of 200 meters, the shelf also allows for fishing techniques, such as giant trawling nets, that would be impossible in deeper waters, Coluccio explained.

“Nobody would fish with a trawl net at 5,000, 6,000 meters,” Coluccio said. “But at 200, 250 meters, yes.”

Foreign fleets trawl the edge of the shelf. They are “always around mile 201,” he said. “Why? The fish spillover from the Argentine shelf and enter international waters.”

Dark Fleets Lead to Dangerous Chases

The presence of foreign boats at the edge of Argentina’s 200-mile Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) is not illegal. But they take advantage of being just beyond the arm of Argentina law, engaging in a range of illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing practices.

Boats regularly switch off their automatic identification systems (AIS), which broadcast a ship’s identity and position. With their transponders disabled, the vessels raid Argentina’s waters.

The worst offender, experts say, is China’s distant-water fishing fleet. A 2021 report by Oceana, a non-governmental organization that tracks IUU fishing, used satellite data to show that around 433 Chinese-flagged vessels fished for 679,067 hours along Argentina’s EEZ border between January 2018 and April 2021. The vessels disappeared from tracking systems more than 4,000 times.

Other dodgy practices include manipulating GPS positions and identification numbers.

Catching scofflaw boats is difficult. Argentina’s navy, Coluccio said, would need radar-enabled ships in a constant patrol along its EEZ.

“Argentina just can’t watch over it,” he said.

When the navy does catch Chinese vessels suspected of illegal fishing, encounters have turned dangerous. In 2016, a naval vessel was pursuing the Lu Yuan Yu 010 to international waters when the Chinese-flagged squid jigger reversed to force a collision. The navy fired on and sunk the Chinese boat.

Two years later, a similar incident occurred when a navy vessel fired shots at a Chinese-flagged boat that refused to heed warning calls, sparking an eight-hour chase.

Major Sergio Almada, a retired senior officer in the Argentine Naval Prefecture (Prefectura Naval Argentina), said these confrontations endanger Argentina’s sailors and the crews of the ships being pursued. They are “acting with total disregard for life and respect for authority,” Almada told InSight Crime.

Chinese authorities are known for not policing the country’s distant-water fleet, though international maritime law says they must. A transshipment system that allows the fleet to stay in international waters for months or even years paves the way for its rapacious behavior.

Refrigerated cargo ships – known as “reefers” – sidle along the fleet, collecting catch and bringing it to port. Vessels return with food, supplies, and fuel.

In international waters, the vessels are not required to abide by Argentina’s fishing quotas, standards, or laws, said Dr. Rodolfo Werner, Argentina’s senior advisor to the Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition, an international alliance of organizations working on conservation.

“There is no authority to apply because there is no law, no clear limits,” Werner told InSight Crime. “The legal vacuum gives rise to a bunch of unscrupulous ships without any monitoring, especially Chinese, that do what they want.”

The Fight Against IUU Fishing

After much outrage and criticism by governments and conservation agencies, China has responded to accusations of IUU fishing by claiming to impose stricter penalties on dark ships, tightening transshipment reporting requirements, and banning off-season squid fishing near Ecuador’s and Argentina’s waters. In November 2021, however, the fleet set up along Argentina’s coast a month before squid season opened.

China has long refused calls to declare and limit subsidies to its fishing fleet, without which ships would not have the fuel and other resources to fish nonstop so far from home ports.

SEE ALSO: Chinese Fishing Fleet Leaves Ecuador, Chile, Peru Scrambling to Respond

Argentina has responded by stepping up its enforcement, purchasing four ocean patrol vessels. The navy has also increased its monitoring capabilities by stationing a ship in the Strait of Magellan, a channel linking the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, to identify suspicious vessels.

Officials and conservation experts agree that international efforts and cooperation are critical in the fight against IUU fishing. They have repeatedly decried Uruguay’s port of Montevideo for hosting transshipment vessels.

Javier Garcia Espil, former director of environmental management of water and aquatic ecosystems at Argentina’s Environment Ministry, said the country has made advances in satellite monitoring, control capabilities, and investigations.

But he acknowledges that Argentina has little recourse against fleets operating just outside its EEZ.

The constant plundering of marine life provokes a feeling of “impotence,” Garcia Espil told InSight Crime.

An Ocean of Lights

In satellite images of Earth, the edge of Argentina’s sea shelf appears like an airport runway at night.

The lights are from Chinese squid jiggers that employ hundreds of brilliant bulbs to draw shortfin squid from the deep. The cephalopods, which grow up to a foot in length, have long bodies, short tentacles, and arrow-like fins.

According to Oceana, half of the world’s shortfin squid catch comes from Argentina’s waters. Stocks may be declining.

Though the species has a short life cycle, the overexploitation of juvenile squid will diminish stocks or even exhaust them, said the fisheries expert.

“This situation can’t continue eternally,” he said. “If we don’t act soon, we are not going to have anything more to defend.”

Coluccio, director of the observatory, described the otherworldly lights as “infinite.” When he listens to the radio at sea, he said, a cacophony of languages streams in: Portuguese, Russian, and, above all, Chinese. He said he finds it all unnerving.

“Really, one wouldn’t know if you are 300 kilometers from Argentina or 300 kilometers from China,” he explained.

*Our article misstated the title of Daniel Coluccio. He is the head of the Argentina Maritime Naval Observatory, not the fisheries observatory.

**Milko Schvartzman conducted research and interviews for this report.