In September 1989, Los Angeles police broke open the cheap padlock that was the only security on a warehouse in the northern suburb of Sylmar. Inside they discovered more than 21 tons of cocaine and $10 million in cash, packed into over a thousand cardboard boxes.

The Sylmar haul was — and still is — the biggest cocaine seizure ever recorded. It also marked a milestone in the history of the cocaine trade, then dominated by the Medellín and Cali drug cartels. The tremors in the criminal underworld caused by the seizure would be felt not just in Latin America and the United States, but also across the Atlantic in Europe.

*This article is part of an eight-part investigation that traces the evolution of the European cocaine trade and the Latin American and European criminal networks that have shaped it. The series is the product of field work and investigations over two years in more than 10 countries in Latin America, the Caribbean and Europe. Read the complete investigation here or download the full PDF.

At the time of the seizure, crackdowns on the Colombian cartels’ favored air and sea routes through the Caribbean had seen them grow increasingly dependent on the Mexicans’ ability to move drugs across the US border. And the Mexicans knew it. In Sylmar, the cocaine in the warehouse was being held hostage by Mexican traffickers who refused to release it to its Colombian owners as a dispute raged over payment.

According to the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), the staggering financial loss of the seizure drove the two sides to thrash out a new deal to avoid any such standoffs in the future. The Colombians began to pay the Mexicans not with cash but with up to 50 percent of the cocaine from each shipment. Over time, the model spread, and the Mexicans became not just transporters, but also owners of the cocaine and the major distributors in the United States.

As the DEA concluded in its official history of the drug trade, “[t]his shift to using cocaine as compensation for transportation services radically changed the role and sphere of influence of Mexico-based trafficking organizations in the US cocaine trade.”

SEE ALSO: European Drug Report Shows Advances in Trans-Atlantic Drug Trafficking

Within a decade, the balance of power in cocaine trafficking to the United States had decisively shifted to the Mexicans, who established a stranglehold on the US border crossing points, reducing the Colombians to the role of suppliers.

The Colombians were left with two options. The first was to fight the Mexicans and seek to break their monopoly in order to regain direct access to the world’s biggest cocaine market. This would involve not only challenging the ever more powerful – and violent – Mexican cartels on their home turf but also making the Colombians priority targets for the US’ increasingly belligerent anti-narcotics efforts. Or, they could cede the US market to the Mexicans while turning their attention to new markets with higher prices and lower risks markets like Europe.

The Shift to Europe

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) estimates that in 1998, as the Mexicans were starting to tighten their chokehold on the US market, 267 tons of cocaine were trafficked into the United States, compared to 63 tons to Europe. Ten years later, the US market had declined 38 percent to 165 tons. The European market, meanwhile, had grown 98 percent, rising to 124 tons.

Perhaps even more tellingly, the UNODC estimated that by 2009, trafficking to Europe was the source of half of the profits made by cocaine traffickers in South America, Central America, and the Caribbean, while the US market accounted for a third. Another decade on, and that gap has almost certainly widened.

Cocaine trafficking into Europe is now hitting historic highs. In 2017, authorities in the European Union (EU), Norway, and Turkey seized a record 142 tons of cocaine, twice as much as the year before and over 20 tons higher than the previous record, according to the EU’s annual drug report.

The same report estimates that 100 to 137 tons of cocaine was then consumed in the region that year. However, even at the upper end of this estimate, this would mean European authorities seized over half of all the product cocaine traffickers tried to ship into Europe, which would represent a startling — and highly unlikely — success rate.

International law enforcement and underworld sources in both Europe and the Americas say they expect around 15 to 20 percent of shipments to be seized at any one link in the supply chain. This would equate to 568 to 804 tons successfully trafficked into, or through, Europe in 2017.

Yet even this huge figure may not reflect today’s situation. Since then, major entry points such as Belgium, the Netherlands, Italy, the United Kingdom, and Germany have all posted huge increases in seizures. If these are representative of a broader regional trend, the current figure may be hundreds of tons higher.

In part, the rise in seizures may be explained by European security forces getting better at seizing cocaine. But this alone does not stand up as an explanation. According to the 2019 EU drug report, wholesale prices have been in a long-term decline, while purity levels have been increasing and retail prices remained stable or fell slightly — all indications that the market is not short of product.

Data on seizures and consumption suggest the US market nevertheless remains slightly larger. Quantity, though, is just part of the story.

Europe remains a more lucrative market than the United States. Calculations by the UNODC indicate that the average wholesale price in Europe in 2017, weighted by population, was $41,731, compared to $28,000 in the United States.

Europol estimates that the EU retail market was worth between 7.6 and 10.5 billion euros (approximately $8.4 to $11.8 billion) in 2017. But calculating using the 568 and 804-ton range and the UNODC prices, then Europe’s cocaine wholesale market could be worth between $23.7 billion and $33.6 billion. However, it is likely that a significant portion of the cocaine entering Europe is in transit to other parts of the world.

Drug traffickers, though, not only look at the rewards; they also weigh the risks. And while trafficking to the United States today is fraught with risk, in Europe, the odds are stacked heavily in the criminals’ favor.

The United States has waged a relentless “war on drugs” in Latin America since the 1980s, and while this has done little to reduce drug consumption or lessen the societal impact of organized crime, the Americans have become highly adept at two things: seizing drugs and locking up drug traffickers. European authorities, in contrast, have a light footprint upstream and have shown limited interest in prioritizing the arrest, prosecution, and incarceration of Latin American traffickers.

The differences between the two approaches can be illustrated with figures. According to the US Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONCDP), the United States spends $17.4 billion on supply-side reduction, which includes drug interdiction, law enforcement investigations, and prosecutions. While no such precise figures have been published by the EU, the data available suggests the EU spends between $3 and $4 billion on supply-side reduction.

Extradition numbers also show the contrast. While publicly available data is patchy, it allows for some comparisons. A European Commission study of extradition between Europe and Latin America and the Caribbean between 2008 and 2011 showed European nations extraditing an average of 61 people from the region a year. In contrast, between 2002 and 2010, the United States extradited an average of 137 people a year from Colombia alone, according to an investigation by El Tiempo.

Europe has one final advantage over the United States for the traffickers — it is a far more open market. The Mexican cartels maintain their grip over US borders, controlling them with extreme violence. In doing so, they maintain their monopoly over much of the wholesale cocaine market in the United States, reducing traffickers from other countries to the roles of suppliers and transporters.

But there are no such barriers in Europe, where anyone with the capital, contacts and know-how, can enter the cocaine market. There are also countless routes into the continent. As such, Latin American traffickers can significantly increase their profits by selling on the European wholesale market while reducing their risk — and European mafias can come upstream to increase their share of the profits.

The Changing Face of the Cocaine Trade

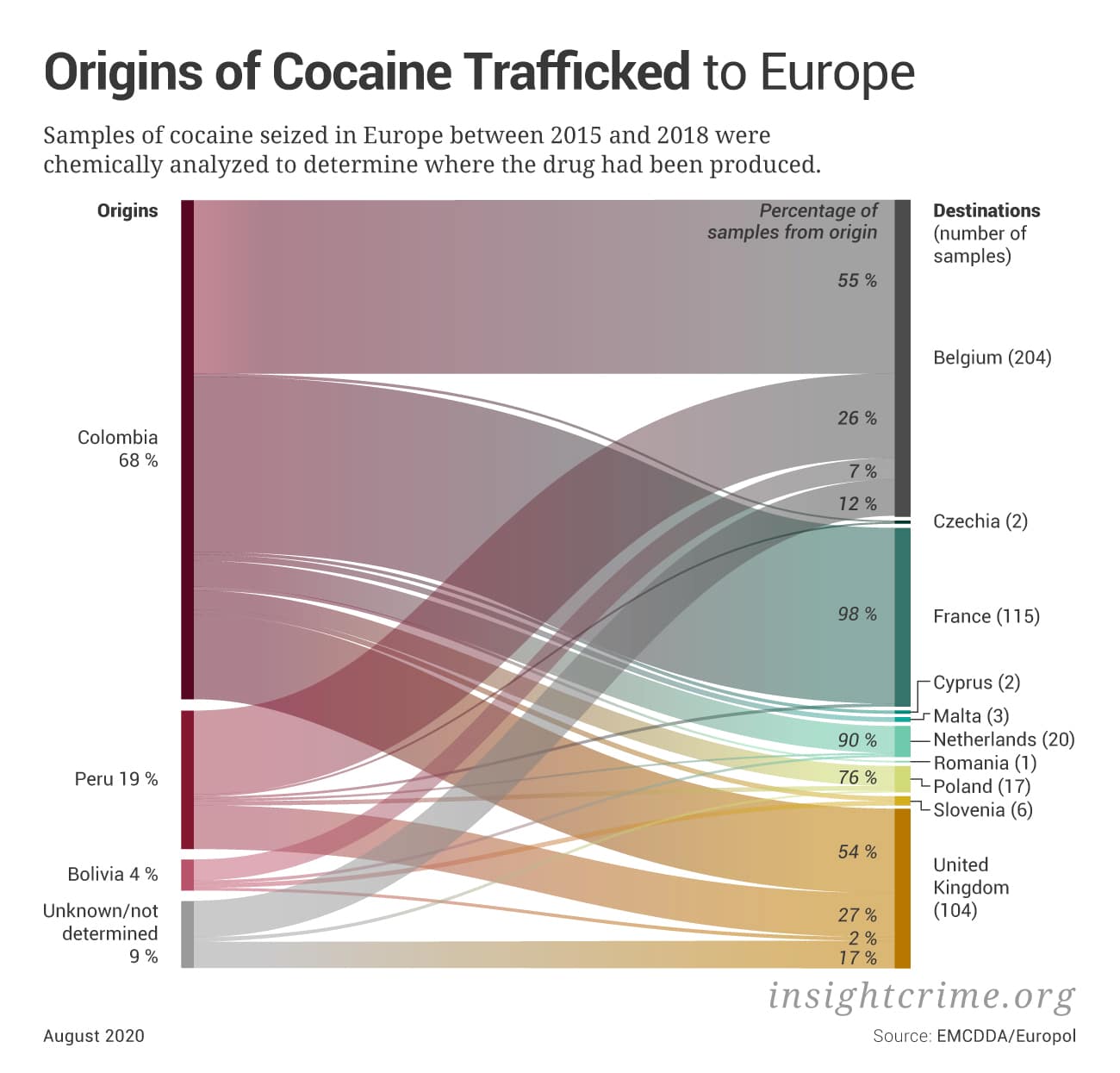

Today, cocaine production is booming. Colombia has seen a year-on-year increase in cocaine production since 2012. The latest monitoring results from Peru and Bolivia, which according to chemical analysis of seized drugs, account for around a quarter of the cocaine entering Europe, show a 36 and 10 percent rise in coca cultivation respectively. The world is awash with cocaine.

In Colombia, members of the Mexican cartels are an ever more common sight. They dispatch their emissaries to strike deals, and to monitor and oversee production and trafficking. They have even financed Colombian armed groups to ensure a constant flow of cocaine, according to multiple investigations.

However, this is not a sign of strength or an indication that the Mexicans are taking over the Colombian drug trade. It is a sign of their frustration with the increasingly fragmented and decentralized Colombian underworld and the difficulty they have getting the cocaine they need to feed the US market.

From the mighty trafficking federation of the Norte del Valle Cartel (NDVC) to the guerrillas of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia – FARC), all of the most reliable Colombian suppliers have splintered into a multitude of much smaller networks. This makes it difficult for the Mexicans to guarantee the consistent supply of large quantities of cocaine they need to keep their supply lines fed.

For the Colombians, selling cocaine to the Mexicans for the US market still accounts for a large percentage of their business. But for many traffickers, the European market is now their priority. The kilo they might sell for $3,000 to the Mexicans goes for more than ten times that on the wholesale market in Europe.

SEE ALSO: Middleman Linked Colombian Gangs with Israeli, Japanese Mafia

With more cocaine to move than ever before, Colombian traffickers have also been aggressively developing other markets around the globe, some with incredible and barely tapped potential. Markets like China, with its vast population and growing prosperity. Or Australia, where wholesale cocaine prices ranged from $110,000 to $154,000 per kilo in 2018, according to the UNODC, a markup that could run as high as over 7,000 percent for Colombian traffickers.

The signs of the entry into these markets of big-time traffickers are clear. Previously, Asia and Oceania were largely fed by small-volume trafficking using mules or courier mail. However, in recent years, these countries have begun to see shipping containers arriving at their ports with hundreds and even thousands of kilos. In September 2019, Malaysian authorities seized 12 tons of cocaine in one shipment alone.

Nevertheless, for the time being, Europe’s market size, prices, risk levels, and its shipping infrastructure moving millions of tons of goods to every corner of the earth make it arguably the most attractive cocaine market in the world. When Colombia’s cartels made their first tentative deals with Galician smugglers and the Italian mafia to move cocaine into Europe in the 1980s, it would have been unthinkable that one day they might shy away from the United States in favor of the old continent. But today, it is a business no-brainer.

*Investigation for this article was conducted by Maria Fernanda Ramírez, Douwe den Held, and Owen Boed.