Methamphetamine is the largest synthetic drug industry in the world and the most consumed stimulant in the United States, far surpassing the consumption of cocaine. It is also fueling the criminal organizations in Mexico responsible for widespread violence and corruption and who use their resources to undermine democracy and the rule of law throughout the region.

Just how big is this market and the precursor market that feeds it? We tried to figure that out in our investigation into the flow of precursor chemicals for the production of synthetic drugs in Mexico.

Meth Production: A Demand-based Model

To estimate the total amount of Mexico-produced methamphetamine (MPM), it is necessary to estimate: how much is likely to be consumed in the main markets; how much is likely to be lost to seizures; and how much is likely to end up as inventory. The total amount of drugs produced in Mexico in any given year would be the sum of drugs sold in their destination markets, minus any inventory from previous years, plus the amount seized by the authorities either en route or in the destination markets.

(Drugs sold) + (Drugs seized) – (Inventory) = (Total drugs produced)

MPM has been seized across all major methamphetamine markets. However, between 2016-2020, international seizure data analyzed by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) indicated the biggest trafficking flows took place from Mexico to the United States, as well as within Southeast Asia and Western and Central Europe with relatively minor inter-regional flows.

These regions also accounted for most of the amphetamine-type drug use in the world in 2020, which would imply that most production of amphetamine-type drugs takes place near the major consumer bases. Furthermore, it appears MPM has made only small inroads in Asian markets; and the latest analysis from Western and Central Europe indicates that Mexican criminal networks appear to rely on strategic partnerships with European networks that operate industrial-production facilities rather than exporting their MPM for sale in the region.

Of course, Mexican criminal networks are constantly attempting to export MPM to new markets. However, these diversification efforts have thus far had a limited impact on the overall market trends and, therefore, on the potential production levels.

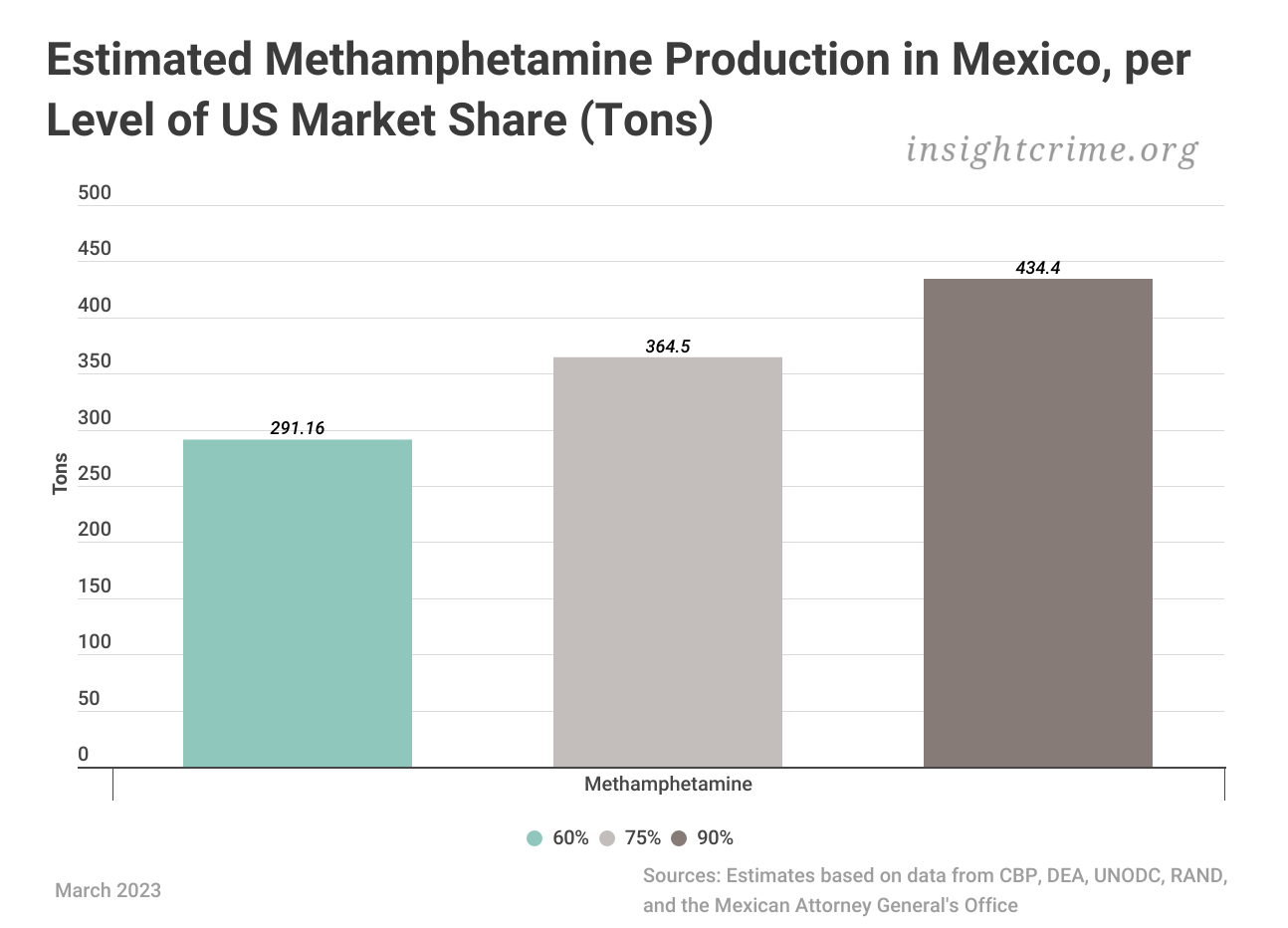

Having identified the United States as the primary market for MPM, the next step is to estimate the demand for both drugs relative to the total consumption, i.e., the market share of MPM. The most recent estimate of total methamphetamine consumption in the United States in 2016 was 171 tons. For that year, the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) estimated that 1.4 million people used methamphetamine. In 2020, the NSDUH estimated 2.2 million people used the drug, a 57% increase.

Since there are no similar estimates of amounts consumed in recent years, we estimated that the total amount of methamphetamine consumed in the United States would have increased by the same proportion. Using 171 tons as our baseline would imply that consumption in the United States could have risen to as much as 270 tons by 2020. By 2022, if we assume consumption rose at the same rate, the United States would have 2.9 million users consuming 351 tons of methamphetamine.

The assumptions regarding the rise in consumption are bolstered, in part, by the data. Obviously, this is not a precise estimate, but it coincides with a steep rise in the amount of methamphetamine seized by the US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) over that same period: from 23 tons in FY2016 to 80 tons in FY2022. All but 7.3 tons of those drugs seized in FY2022 were seized at the Southwest border, the route most closely associated with Mexican criminal networks. Additionally, Mexican authorities seized around 55.3 tons of methamphetamine in 2021, according to data provided by Mexico’s Attorney General’s Office.

SEE ALSO: Methamphetamine Production in Mexico is Toxic For The Environment

Prices have dropped in a similar fashion. In 2016, a kilogram of wholesale methamphetamine in the United States cost about $17,000; in 2022, the cost was closer to $3,500, according to two InSight Crime interviews of counterdrug agents in California. This is in line with Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) estimates that most of the methamphetamine available in the United States is produced in Mexico and smuggled through the Southwest border. Furthermore, the DEA says that its seizures of methamphetamine also rose even though there has been a registered decline in the number of domestic labs found in the United States, which would point to a growing MPM market share (although it is not enough by itself to calculate the relative dominance of the Mexican producers).

With these assumptions, it is possible to estimate that Mexican criminal networks produce between 291.16 tons and 434.4 tons of MPM, depending on how much market share we assign to them.

Meth Precursor Demand: A Production-based Model

Having estimated an approximate level of production of MPM, it is possible to do a production-based model for precursors. This is, as will become clear, a complex task, as there are plenty of potential chemicals available, and the actual yield of illegal labs is mostly unknown, so we will not be able to able to make estimates of each of the chemicals.

Still, drawing mostly from the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) ratios of what quantity of precursors and pre-precursors are needed to produce a single kilogram of methamphetamine and fentanyl, we can make some approximations. We can also illustrate that, by tracking these chemicals, authorities can find patterns that assist in understanding the possible flow of these chemicals to criminal networks. Ultimately, however, the sheer variety of the products and usage also points to the policy dilemma of having to balance legitimate trade needs with import bans of dual-use chemicals.

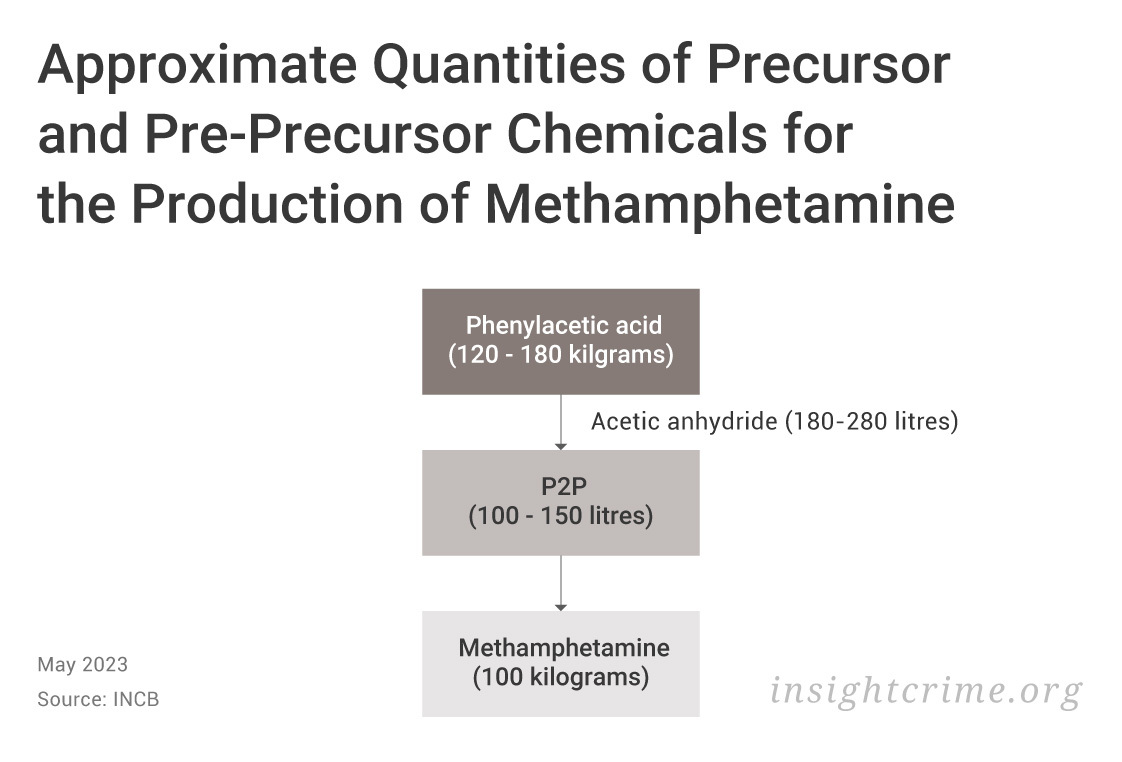

In the case of methamphetamine production, developing these estimates for precursors is relatively straightforward since there is a consensus in the international community that 1-phenyl-2-propanone, or P2P, is currently the primary precursor. P2P also represents a useful standard in terms of determining the ratio of precursor-to-finished product. The INCB, in its 2022 report on precursor chemicals, estimates that a typical method would require roughly a 1.5-to-1 proportion of P2P to methamphetamine. Using our previous demand-based model estimates, the estimated amount of P2P required would then range from 437.4 to 651.6 tons.

From here, it gets more complicated. Even though P2P has long been a scheduled substance, there is reason to believe it is available in the Mexican black market. Mexico is consistently among the top countries with the highest number of P2P seizures, which would be consistent with its position as a major producer of methamphetamine. Most seizures of P2P used in manufacturing MPM occur in clandestine labs rather than at ports of entry, indicating that the majority of the substance is synthesized domestically rather than imported as a finished product. This finding would coincide with experts and law enforcement InSight Crime consulted, who say Mexican criminal groups have been clandestinely manufacturing P2P for years.

SEE ALSO: In Sinaloa, Mexico, a Deadly Mix of Synthetic Drugs and Forced Disappearances

There are several ways to determine how much of this P2P is clandestinely produced in Mexico and how much is imported or diverted. One way would be to track the movement of pre-precursors, the chemical substances that allow for the manufacturing of precursors like P2P. Let’s consider two pre-precursors widely used in a typical production method: phenylacetic acid and acetic anhydride. According to the INCB, to produce one liter of P2P, you would need 1.2 kilograms of phenylacetic acid and 1.8 liters of acetic anhydride. If Mexican criminal networks were only using this method, it would be necessary to source 525 to 782 tons of phenylacetic acid and 787 to 1,173 tons of acetic anhydride to meet the methamphetamine production quota estimated above.

The example is illuminating for many reasons. To begin with, it provides a possible path for authorities to track chemicals. Once they know the typical patterns of consumption and how imports and local production satisfy that consumption, they can look for anomalies. For instance, consider the aforementioned chemicals. The amount of phenylacetic acid mentioned would be equivalent to 134% of Mexico’s legal import total for that chemical for 2021, according to data obtained from the Mexican National Customs Agency (Agencia Nacional de Aduanas de México – ANAM). It would therefore be challenging to obtain this chemical without raising suspicion, indicating that criminal organizations may be synthesizing it in clandestine laboratories, smuggling it in significant quantities, or both. Conversely, the amount of acetic anhydride mentioned represents only 4% of the total legally imported in Mexico in 2021, and 1% to 1.4% of the country’s total production, according to Mexico’s National Association of the Chemical Industry, making it more likely that this chemical is being diverted from import stocks or local production.

Doing this exercise with an essential chemical for P2P, such as a binder or a solvent, yields largely the same result. In 2021, seizures of acetone, for example, increased significantly, which suggests that the method of using acetone as a solvent is being employed more frequently. Since the latest INCB report does not provide an estimate for the yield of acetone used in methamphetamine production, we used a P2P-production method widely available on the internet. According to that method, it would take about 9 kilograms of acetone to produce 1 kilogram of P2P. Assuming all P2P in Mexico was produced using this method, traffickers would have to source between 3,936 and 5,864 tons of acetone, which is almost a quarter of the legal imports of acetone in 2021, according to ANAM. This too would presumably make any attempt at diversion very noticeable, leading to the preliminary conclusion that Mexican criminal organizations are sourcing acetone locally, smuggling it into the country, or both.

Furthermore, the results suggest that criminal networks may be directly sourcing precursors, including highly regulated ones. Take the case of methylamine, a precursor for methamphetamine. The production of one kilogram of methamphetamine, for example, requires just 1.4 kilograms of methylamine, according to the same recipe cited above. This would mean that criminal groups would need between 408 and 608 tons of methylamine to make their MPM.

While this is probably too much to source directly — as it represents about 17% of the legal imports of the derivatives of the product, according to ANAM — it is conceivable that criminal groups are sourcing large quantities. Some of this sourcing may occur through a hybrid method, in which it is obtained legally overseas and then smuggled into Mexico with relative ease behind a third-party façade. Furthermore, the lack of visibility on the local production and provision of some of the required precursors and pre-precursors might incentivize the diversion of local production.

Meth Precursors: Scope of the Profits

Given the limitations established in the production-based model, estimating the scope of profits in this market is difficult. But if criminal organizations sourced their precursors and pre-precursors from the open market, their costs may be low relative to potential profits. What’s more, there may be other costs associated with illegal operations and obtaining an illegally sourced precursor, pre-precursor, or essential chemical. There may also be a significant premium associated with illegal sourcing, but it is still likely very low relative to the product’s final price.

Consider the methamphetamine market and the chemicals cited in the examples in the previous section. According to the data provided by ANAM, the average price for a legally imported ton of phenylacetic acid in 2021 was $2,000; the price for a legally imported ton of acetic anhydride averaged $1,000; and the price for a ton of acetone was less than $1,500. And while the price of methylamine was not available, the value of derivatives like dimethylamine and trimethylamine was around $868 per ton, according to ANAM’s database.

To put these costs into perspective, a ton of MPM in Mexico can sell for between $200,000 to $400,000, according to interviews conducted by InSight Crime. From an MPM producer’s perspective, even if we assume illegal sourcing includes a 300% surcharge, the cost of the pre-precursors and essential chemicals would still be a fraction of the wholesale cost of the finished product in Mexico. What’s more, the final product becomes even more valuable once it crosses the US border.

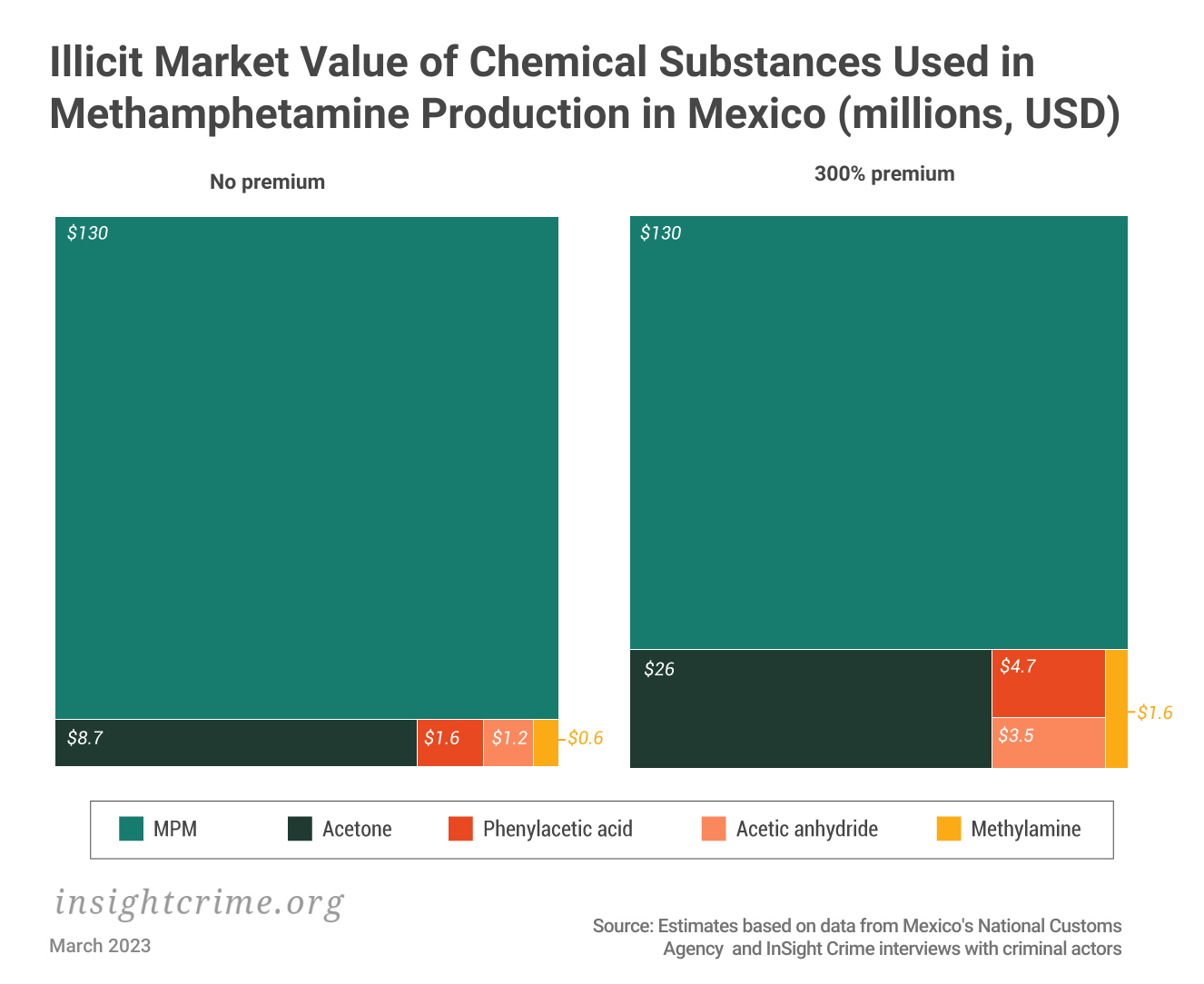

While the value of the illegal precursor market would be relatively small compared to the value of the MPM market in Mexico — and certainly in the United States — it would still be significant for illegal brokers. Based on the previous MPM precursor-cost scenario and the previous production estimates, the illegal acetone market could be worth between $8.7 million and $26 million a year for the maximum estimated amount of MPM produced.

In the same scenario, the methylamine market could range from $528,000 to $1.6 million; the phenylacetic acid market could range from $1.6 million to $4.7 million; and the acetic anhydride market could range from $1.2 million to $3.5 million. These revenues suggest there would be a vibrant market as it relates to precursors associated with methamphetamine production.

*Victoria Dittmar contributed to this article.