Laredo and Nuevo Laredo, sister cities along the US-Mexico border, are almost the same size. They have very similar economic motors, cultural heritage, populations and socio-economic indicators. Yet, in 2012, Nuevo Laredo had at least 36 times the number of murders. Why?

It is a question that is pondered up and down this 1,951-mile border, especially after the explosions of violence in Tijuana and Juarez during the last decade, places that sit across from San Diego and El Paso respectively, two of the safest cities in the United States.

Like those cities, murder rates have traditionally been higher in Nuevo Laredo by a factor of three to five. And few places offer such similarities in what is essentially an isolated geographic space.

Last year was the worst on record in Nuevo Laredo with 288 homicides. Unofficially, it was much worse, with a reported 550 bodies recovered by authorities. Grenades exploded. Bodies were hung from bridges. The city was on a virtual lockdown at night as battles raged through the early part of this year.

It is expected to pick up again after the dramatic July 16 capture of the Zetas’ top commander, Miguel Angel Treviño, alias “Z40.” Treviño’s brother, “Omar,” alias “Z42,” is the presumed leader but does not have his brother’s charisma and will have a hard time holding Nuevo Laredo.

Meanwhile, Laredo had eight murders last year, only one of which authorities said was organized crime-related.

The question in Laredo – Nuevo Laredo becomes even more relevant given the presence of the Zetas, Mexico’s most volatile and unpredictable criminal organization and also the group most frequently cited as inciting “spillover violence” in the US.

Reason Number 1: The Zetas

Homicide rates for both cities increased when the Zetas arrived. In part, this is because the Zetas are not like other criminal organizations. Their core was former military personnel who broke many of the traditional rules of the Mexican underworld. Their focus is on finding and controlling territory, so they can extract “rent” or what is known as “piso,” from the other underworld actors. In Nuevo Laredo, this financial portfolio included a vital extra: they themselves got into drug trafficking.

The Zetas arrived around the year 2000, and Nuevo Laredo’s homicide rate has been consistently higher ever since. The group, then the armed wing of the Gulf Cartel, was sent to help secure passage through this, the most important commercial crossing point on the border. They did this by recruiting knowledgeable locals such as Miguel Treviño.

Treviño had started as a gopher for the Nuevo Laredo traffickers (he is often referred to by his rivals as “lavacarros” or “car washer”) but had since graduated to management. He quickly defected to the Zetas who would later rely on his knowledge to rid them of the local power brokers.

At the time, the most prominent group in Nuevo Laredo was Jose Dionisio Garcia, alias “El Chacho,” and his organization, aptly named “Los Chachos.” Like any other outsider organization, the Gulf Cartel paid “piso,” or a “toll,” to Chacho to use the area as a corridor.

There are many stories regarding what happened next. According to one report that cited a Gulf Cartel informant, Chacho double-crossed the Gulf Cartel and, with the help of the local authorities, tried to steal a drug shipment. Anabel Hernandez, in her book “Los Senores del Narco,” says the Gulf simply decided to take it. In either case, the Zetas, who were recruited from Mexico’s Special Forces, kidnapped and killed Garcia.

The Zetas spent the next four years securing the Nuevo Laredo “plaza,” Mexican parlance for illicit corridor. It was not easy. They faced a cadre of local traffickers, many of who were loyal to Chacho or at least not loyal to them. And when the Gulf Cartel boss, Osiel Cardenas, was arrested in 2003 (he would later be extradited to the US), some of these local traffickers staged a revolt, refusing to pay their new overlords the “piso.”

One of these local traffickers was Edgar Valdez Villareal, alias “La Barbie.” Like many of the soldiers in this battle, Barbie grew up in Laredo and had fled to Mexico when his drug trafficking crew was busted by US law enforcement. According to Rolling Stone, when Cardenas was arrested, Barbie went to Monterrey and convinced the Beltran Leyva Organization and the Sinaloa Cartel to team with him and retake Nuevo Laredo.

Homicides per 100,000

(Sources: INEGI, Secretario Ejecutivo del Sistema Nacional de Seguridad Publica, FBI)

Barbie would become legendary for a ferocity matched only by his chief rival, Miguel Treviño. The spat was personal. The Zetas killed one of Barbie’s associates. Barbie later killed Treviño’s brother. Treviño found and killed another Barbie associate and raped his granddaughter, Rolling Stone says. Barbie’s brother was also assassinated.

The fight also spilled into Laredo, which is the only time Laredo’s murder rate actually approached that of its sister city. The assassinations paralleled the type of hits occurring in Nuevo Laredo: in parking lots, outside of houses, at stoplights. This was, and remains, one of the few real cases of spillover violence from Mexico.

Many say that the splurge of violence in the area is anomaly that can be blamed on the Zetas. To be sure, the Zetas are the some of the most vicious and predatory of organized criminal groups. A study by Harvard University revealed that between 1999 and 2010, the group had moved into more municipalities than any of its rivals.

The Zetas were an anomaly in many respects, but so are some their rivals. Barbie’s evildoings, for instance, at least matched the Zetas’ barbarities. Indeed, the Zetas battle with Barbie heralded a significant change in the underworld in which there families were targets and media would be used as a tool to fight the wars. For some analysts, this was more Barbie’s doing than the Zetas.

Reason Number 2: Rule of Law

There was a major difference in how the authorities on both sides of the border reacted to the Zetas, which seems to be at the heart of why violence does not proliferate on the US side of the border.

The Mexican forces completely capitulated. By 2011, Tamaulipas state authorities had disbanded the police. It has not been reconstituted. Instead, the army is responsible for security, which has resulted in a de facto abdication of the streets.

And while at first, the US security forces were startled, they quickly regrouped, and using interagency cooperation, they zeroed in on the hitmen who were crossing into Laredo to target suspected “Chapos,” the allies of the Sinaloa and the Beltran Leyvas.

The head of those hitmen was Gabriel Cardona, alias “Pelon.” Cardona was born in San Antonio and moved to Laredo when he was four, according to an account of the time period in Esquire magazine in which the reporter interviewed Cardona. He first shot a man outside a bar in Nuevo Laredo when he was just 14, Esquire says. He did not get caught and the message was clear: there are no consequences for murder in the sister city.

The Zetas tried to set up similar operations in Laredo, intimidate law enforcement as they had in Nuevo Laredo, and murder suspected witnesses and weak links in the group. But the US law enforcement quickly got ahead of them. (See below the Center for Investigative Reporting’s interview with Rosalio Reta, a former member of Cardona’s Laredo crew.)

By 2004, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) had already flipped a key member of the organization named Rocky Juarez. Juarez testified in court that he moved to Nuevo Laredo around the year 2000 to start working with the Zetas. His job was to pay off police officers and keep them on the “payroll,” as he called it.

By then, the Zetas controlled the Nuevo Laredo police, which gave them the upper hand in their fight against Barbie. Another witness in the case against Cardona’s cell, Mario Jesus Alvarado, testified about how different Nuevo Laredo was when he traveled there to do drug deals with the Zetas in the early 2000s.

“I started seeing a little difference as far as carrying guns, driving, and stuff like that,” he told the court. “Getting pulled over and the cops not messing with you. They pulled us over, and the cops let us go and stuff like that for speeding or whatever.”

When the Zetas became more “aggressive, more violent,” Juarez returned to the US and signed a deal with the DEA. Shortly thereafter, Juarez rented a safe house where the DEA installed cameras to watch the Zetas cell in real time. By then, the authorities were also tapping their phones and could listen as they prepared an attempted hit in 2006, just outside a Laredo nightclub. To thwart the hit, the police pulled the driver over and pretended to arrest and impound his car. The driver was lucky: he was the wrong target.

Juarez also was an errand boy for hitmen sent from Mexico. They were typical of the Zetas’ recruits. Like Cardona, they were young, brash and unprofessional. At one point, they sent Juarez to buy condoms and bring them cocaine in their hotel. They did little to conceal their identities with outsiders, and bragged to Juarez they were going to “kill…at least 50 persons (sic)” at a nightclub where one target had been identified by one of the Zetas’ many female lookouts.

“We need to kill a lot of people, so we can make our point here,” Juarez told the courts the two assassins had said to him. “So they can know who the Zetas are.”

But the two assassins never reached their target at the bar. Nor did they kill “50 persons.” In other words, what passed for professional and feared on one side of the border, was amateur on the US side. And while their impact was real during those first years, US law enforcement reaction limited the damage and sent a message to the Zetas that operating in the US would be, in a word, different.

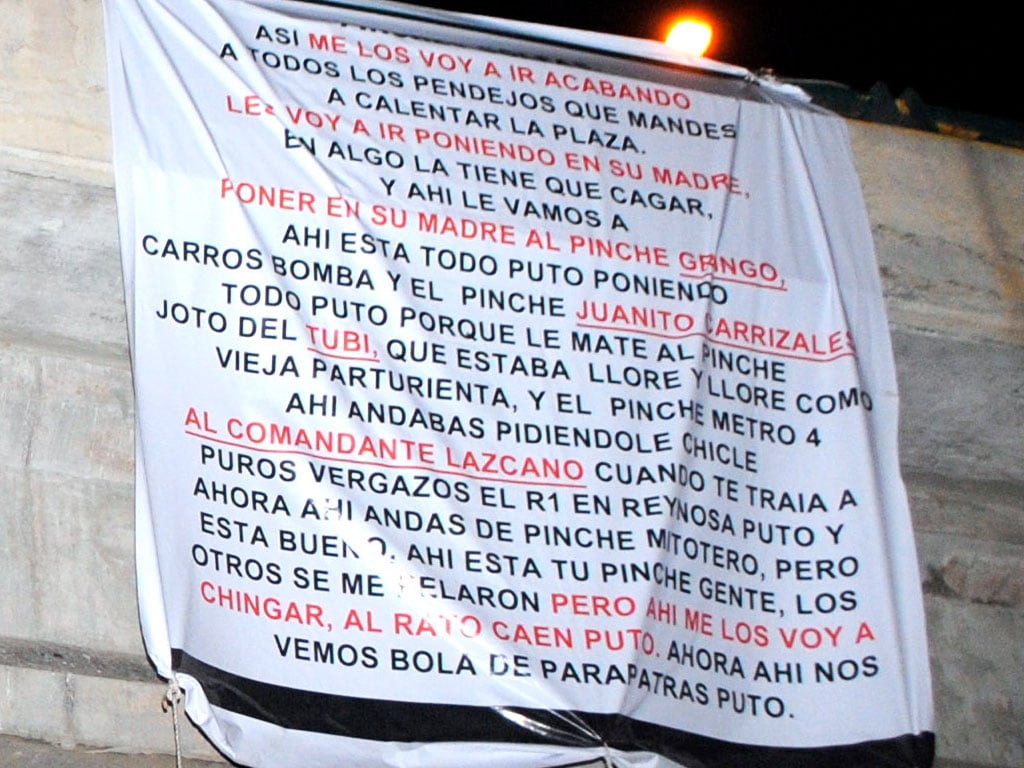

On the Nuevo Laredo side, the Zetas prevailed, in part by filming their own gruesome torture sessions of their rivals and intimidating anyone who stood in their way. (Four police chiefs have gone missing or been killed since 2005 in the city.) The video sessions would become part of these organizations’ tactics as the fight in Mexico became considerably less gentlemanly.

The murder rate in Nuevo Laredo would drop after the Zetas consolidated their hold on the city only to go up again in the last three years after the organization broke from its progenitor, the Gulf Cartel, and splintered.

However, on the US side, the Zetas’ cell was decimated. Twelve members, including at least four who pulled the trigger on murders in Laredo, were jailed and prosecuted. Most of them, including Cardona, remain in prison.

*The research for this report was made possible by the generous support of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholar’s Mexico Institute and the University of San Diego. The work was funded as part of a coordinated joint project on civic engagement and public security in Mexico. See full series of papers here.