It was the Day of the Dead when the body of Celso Delgado was carried off the Verdemilho, a Portuguese-flagged vessel that fishes in the South Atlantic.

Celso Delgado had been working on the boat with his brother Raúl when he grew increasingly ill over a period of weeks. In his last days, Celso lay on the floor, unable to speak and gasping for air.

“I had to be there with a piece of cardboard fanning him, because he couldn’t breathe,” Raúl told InSight Crime.

On November 2, 2020, the Verdemilho finally docked at Uruguay’s port of Montevideo. Celso had already been dead for a day, his body placed in the ship’s freezer.

Between 2013 and 2021, Montevideo was the last port of call for 59 deceased fishing crewmembers – or one about every month and a half, according to figures provided by the Montevideo Port Prefecture (Prefectura del Puerto de Montevideo), the port’s law enforcement body. Conservation and human rights groups have long accused the port of hosting vessels known to engage in abuse at sea. Crew members have, at times, alleged being beaten and locked aboard ships. More often, they describe being starved and forced to work for days without sleep.

They have also been refused necessary medical treatment, which is what Delgado, who is from Peru, alleges happened to his brother.

Days after his brother’s death, Delgado gave a sworn statement to a Montevideo Prefecture official. His attorneys, who are law students, later filed a formal criminal complaint with prosecutors, asking them to charge the captain and the maritime agent responsible for the vessel with culpable homicide, omission of assistance, and crimes against public health. More than two years later, the case is still under investigation by Prosecutor Silvia Porteiro, who is part of the Attorney General’s Office in Montevideo, according to an email from Javier Benech, the director of communications for Uruguay’s Attorney General. No formal criminal charges have been filed.

Delgado alleges that he and his brother had asked the ship’s captain to allow Celso to be treated by a doctor even prior to the ship heading out of port on October 2. As crew from Peru, they were not permitted to leave the boat. According to Delgado, Celso had already developed a cough, a symptom of COVID-19. The captain refused, and the Verdemilho returned to the Atlantic, trawling for fish.

“What he preferred was filling the boat,” Delgado said.

InSight Crime attempted to reach Verdemilho captain Ruben Blanco Martínez through emails to his attorneys and calls to his cell phone, but they went unanswered. He has denied Delgado’s account in previous statements to officials. Emails to maritime agent Pedro Santana S.A. also received no response.

A Port with a Bad Reputation

At the southern tip of the country, Uruguay’s port of Montevideo serves as a clearinghouse for fishing fleets operating in the South Atlantic. The port unloaded nearly 76,000 tons of frozen fish in 2021, according to Uruguay port administration figures.

Uruguay scores quite well on international measures of illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing, such as the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime’s IUU Fishing Index. According to the index, Uruguay is among the 25 best countries in the world in its efforts to counter IUU fishing.

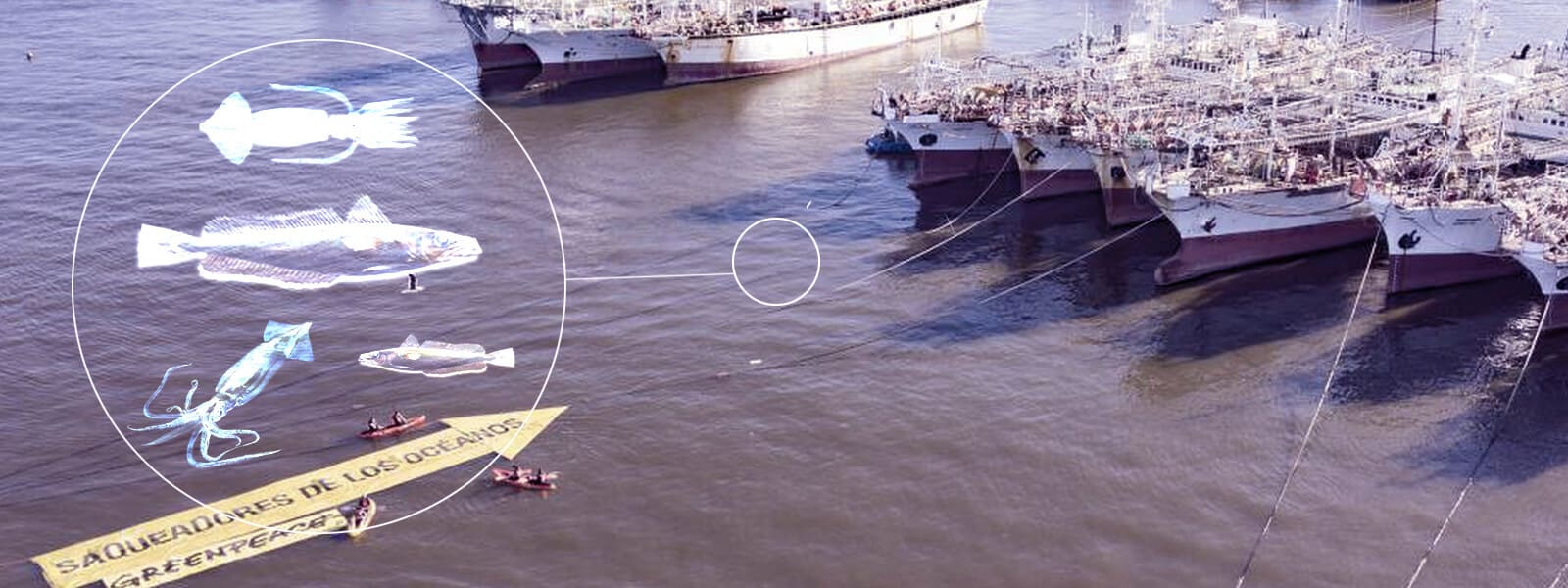

Despite the country’s strong national record, Oceana, an international non-profit dedicated to ocean conservation, exposed the port as the second most visited by transshipment vessels in 2015. Transshipment abets IUU fishing through the use of refrigerated cargo ships that meet fishing fleets, shuttling them supplies and receiving catch. Distant-water fleets employ the transshipment system to fish for months just outside a country’s 200-nautical-mile Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ).

Boats turn off transponders known as automatic identification systems (AIS), which broadcast a ship’s identity and position, to illegally hoover waters inside exclusive zones. A 2021 Oceana study examined transponder data from 800 vessels fishing just outside of Argentina’s EEZ between January 2018 and April 2021. Just over 30 percent of the boats that shut off their transponders docked at the port of Montevideo.

“The foreign fleets leave a lot of money in the port,” said Mariana Silvera, an Uruguay consultant to the National Geographic program Pristine Seas.

“For that reason, it’s not convenient to do things correctly and carry out inspections and controls,” Silvera told InSight Crime.

IUU Fishing and Labor Abuse

Illegal fishing is known to be coupled with other crimes, particularly labor abuse at sea.

The campaign Oceanosanos, which focused on ocean conservation and illegal fishing in Uruguay, compiled a 2018 report of boats accused of misconduct that docked at the port of Montevideo. Accounts included a Taiwanese fishing ship that visited the port twice in 2017 before being inspected in South Africa, where authorities documented that crew members had been “beaten, suffered mistreatment and were not paid the agreed amount.”

In 2014, more than two dozen African crew members fled a Chinese fishing ship at Montevideo. They said they had been attacked with tools, and their legs showed signs of being shackled.

Various nationalities crew the vessels that dock at Montevideo, said Jessica Sparks, the associate director of the ecosystems and environment program at the Rights Lab at the University of Nottingham, England.

“It’s a big port for vessels that are out at sea for very long periods, and that, of course, escalates risk “of abuse, Sparks told InSight Crime.

The port serves as a base for bringing in crew members from Peru, Indonesia, Africa, and elsewhere, said Alexis Pintos, spokesman for the National Union of Seafarers and Allied Workers in Uruguay (Sindicato Único de Trabajadores del Mar y Afines – SUNTMA).

SEE ALSO: Coverage of Uruguay

On the rare occasions when abuse is reported, it’s often to the union.

“Crew members of all nationalities have told us about having their documents confiscated, of mistreatment, of going without food,” said Pintos. Little is done to counter misconduct, the SUNTMA spokesman said.

“Since the flag is not Uruguayan, we look the other way,” Pintos told InSight Crime.

The Last Port of Call

Dead crew members don’t speak. Investigations are rare. Delgado, though, believes his brother died needlessly. On October 14, Celso grew sick enough that the captain had him seen by a telehealth doctor, who prescribed some medication. His health improved but then worsened. The boat fished until October 27 before the captain turned for port.

According to an autopsy report, Celso died from a type of pneumonia. There is no mention of COVID-19.

Delgado, however, alleges that the captain told his brother while they were at sea that he couldn’t bring him a doctor while at port because a COVID-19 diagnosis would have caused the ship to be quarantined for weeks.

Delgado said he took the risk of filing the complaint, despite being told by other brothers, who were also working on the ship, that it would amount to nothing.

“I made the complaint because of how my brother was treated, because I don’t want this to happen to other (fishing) crewmembers – that they die without being attended by a doctor,” he said.

*An investigator in Uruguay contributed reporting and interviews to this report.