A new report describes the shifting role of an unnamed female crime boss in Medellin’s fractured mafia, evidence that the organization that once controlled Colombia’s second-largest city has seen some dramatic shifts in leadership.

The Semana news magazine report describes the woman’s rising role in Medellin’s Oficina de Envigado, referring to her only as alias “Helenita.”

While the Oficina de Envigado originally started as a group of hitmen in the service of infamous crime boss Pablo Escobar, it evolved into the primary city mafia after Escobar’s death. Helenita apparently was first employed by the Oficina’s original leader, Diego Murillo, alias “Don Berna,” although her initial contact was Daniel Alberto Mejía, alias “Danielito,” the Oficina’s third-in-command who had some 70 gunmen directly under his command.

Helenita helped manage the Oficina’s financial accounts, specializing in real estate, according to Semana. The Oficina used the facade of these land and business holdings — including beauty shops, night clubs, and country estates — to disguise the origin of their illicit proceeds from extortion and the drug trade.

Authorities reportedly first took note of Helenita in 2004 when going through Don Berna’s estate records, where she was listed as the manager of a banquet hall linked to Berna’s holdings. During that time, Don Berna’s paramilitary group was participating in the government’s demobilization process, and Don Berna surrendered, continuing to run his criminal enterprises from prison.

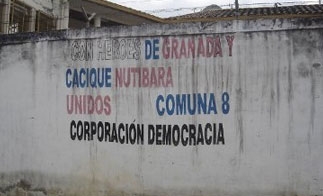

According to official records, Semana reports, Helenita was also listed as working as an official administrator for Corporacion Democracia, an NGO that provided support to demobilized paramilitaries. The NGO was also a mouthpiece for the paramilitaries’ political interests, and served as a cover for laundering dirty cash on the Oficina’s behalf.

While the Corporacion was never formally dismantled, in 2008 one of its directors was gunned down in a Medellin restaurant, in a killing that the authorities have never solved. The remaining director resigned in 2009.

But before the Corporacion unraveled, in 2007 Helenita helped found another non-profit organization, unnamed by the Semana report, which is apparently registered as a gang prevention project. Semana notes that this organization won contracts from several mayor’s offices in the Valle de Aburra metropolitian area (which includes the municipalities of Medellin, Envigado, Bello, Itaguia, and six others). But at no point was Helenita’s business background scrutinized.

The Semana report says Helenita is one of the few first-generation members of the Oficina to remain active and at large, as the organization fractured into warring factions, making it a shadow of its former self. According to Semana, she has survived primarily by keeping her head down, and handling most of the Oficina’s technically legitimate activities, in connection to administering the mafia’s businesses. Notably, she has never been charged with a crime.

And she has expanded her duties. According to Semana, Helenita handled the Oficina’s political agenda during the 2011 local elections, selecting and backing select city council candidates, and deploying gang members to drive out the vote for their candidate of choice. Controlling local politicians is of particular interest to organizations like the Oficina, as they influence the municipal budget, as well as the security forces and judiciary. The Semana report also claims that Helenita is in charge of much of the Oficina’s extortion operations, including the payments from one of Medellin’s largest public marketplaces, the Mayorista.

While Semana’s leading angle is perhaps misleading in asserting that Helenita is now “at the top” of the Oficina’s hierarchy, the report is helpful in illuminating just how much of the Oficina’s activities have little to do with their most infamous operations: the trafficking of drugs. Similarly to any organized criminal group, a large part of the Oficina’s activities involve maintaining a veneer of legitimacy: running businesses, signing papers, keeping accounts. Such “administrative” roles are a key leg in holding up any criminal organization.

Colombia does have a history of women playing powerful roles in criminal cartels. The most infamous one is Griselda Blanco, a Medellin native who was one of the first Colombians to see the potential of the cocaine trade in the 1970s, and constructed a smuggling network between Colombia, Miami, and New York.

In Mexico, there have been reports that women are increasingly assuming roles beyond the one they typically play in the underworld. While women are usually depicted as working as drug mules or targets for cartel-related assassinations, Mexico’s National Women’s Institute and the military have both said they have evidence that women are taking on more responsibility in some criminal organizations. High-profile arrests like the capture of an alleged female Zetas commander accused of killing 20 people have helped feed such perceptions. It is less clear whether Colombia is seeing a similar trend, but doubtlessly Helenita will continue to be held up in the media as an example of the powerful roles that women play in organized crime.

Helenita’s ascension in the Oficina de Envigado is also an indication of just how much the organization has transformed in recent years. Currently, one faction of the Oficina — led by Erick Vargas, alias “Sebastian,” — is fighting an outsider group, the Urabeños, based principally along the Caribbean coast, for control of the city. As the Semana report highlights, with Helenita now thought to control another faction of the Oficina, it’s clear there is no longer a single criminal group that exerts hegemony over Medellin’s underworld.