In the heart of some of South America’s biggest cities, local authorities have ceded control of drug slums to organized crime groups. InSight Crime identifies three such places where violent gangs have imposed their own form of justice, often with the complicity of state agents.

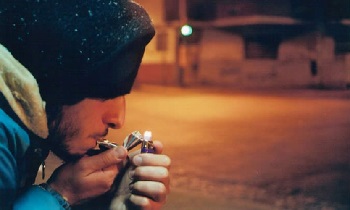

Paco Villas: Argentina

Within the urban heart of Buenos Aires and in some cases only meters from the city’s most expensive neighborhoods are Argentina’s notorious “villas.” These urban slums are the capital’s main drug hubs, where criminal groups from across Latin America have helped flood the local market with “paco” — a highly addictive crack-like substance. With drug trafficking through Argentina intensifying over the past few decades, local consumption has begun to grow.

Today, Buenos Aires’ drug trade is largely divided between Villa 1-11-14 in the “Bajo Flores” neighborhood, Villa 31, and Villa Zavaleta (or Villa 21-24), according to Lucas Manjon, manager of Human Trafficking, Drug Trafficking and Organized Crime-Related Activities for the Common Good Party (partido Bien Común) and the Alameda Foundation (Fundación Alameda).

At least 10 drug trafficking organizations operate in these “villas,” seven of which are based in Villa 1-11-14 and Villa 31. Their territorial control shifts from slum to slum as a result of bloody turf wars and new rivalries.

Villa 1-11-14, for example, has seen territorial feuds between Peruvian, Paraguayan, and Colombian drug gangs. A massacre during a religious procession in 2005 marked the moment in which a former guerrilla fighter for Peru’s Shining Path, Marco Antonio Estrada González, alias “Marcos,” assumed total control of drug activities in the slum. His rival, another former Shining Path insurgent named Alionzo Rutillo Ramos Mariños, alias “Ruti,” was forced to move into Villa 31. Since then, a group of Paraguayan criminals has also been increasing their power in Villa 31.

SEE ALSO: Shining Path News and Profile

In Villa Zavaleta, smaller groups made up of Peruvians and Bolivians, among other nationalities, manage the local market.

For these gangs to be able to operate freely despite a continuous state presence in Buenos Aires’ villas, there is strong collaboration between criminals, security forces and politicians, Manjon told InSight Crime. He described this as a “para-state” operation, in which dirty money gets pushed high up the ranks.

As part of this agreement, criminal groups fill the state’s absence in these poor neighborhoods, imposing norms, administering their own form of justice and resolving conflict within a system set up with the complicity of state authorities themselves, according to Manjon.

One peculiarity of these criminal groups is that they have set up urban cocaine laboratories to produce drugs for international export, Manjon explained. Numerous laboratories allegedly belonging to relatives of drug boss Marcos have been found in the Bajo Flores neighborhood. It has been estimated that up to 50 percent of cocaine produced in Bajo Flores leaves the country, while the rest is sold on the domestic market.

But drugs are not the only trade lining the pockets of these groups. Sexual exploitation and forced labor in garment factories are also a reality in the villas.

At the end of 2015, police intelligence placed the criminal earnings within Bajo Flores neighborhood at between $700,000 and $1 million per month, Manjon told InSight Crime. Of this total, $250,000 is allegedly filtered to police in bribes.

Still, calculating the amount of cocaine being produced in Buenos Aires is challenging. To date, the biggest seizure to have been made in the capital’s villas was of only 30 kilograms, Manjon said.

‘The law of the favela’: Brazil

Brazil’s “cracolândias,” or cracklands are perhaps the most well-known of Latin America’s stateless communities. Today, Brazil is one of the world’s largest cocaine and crack markets. Within the favelas — very large, low-income neighborhoods — of the country’s major cities, powerful drug gangs with international reach control the buildings, streets or lots where drug addicts spend their days.

In 1991, the first reports on the existence of a crackland appeared in the southern city of São Paulo, according to Bruno Gomes, who worked as a psychologist in the city’s crackland for 11 years until 2014. Currently running these areas are low-level members of the First Capital Command (Primeiro Comando da Capital – PCC), an international drug trafficking organization that was born in São Paulo’s prisons in the 1990s.

SEE ALSO: PCC News and Profile

It took some time before crack started flooding other major Brazilian cities. One theory is that the PCC introduced the drug into other states, including Rio de Janeiro, where it appeared in 2004, Gomes told InSight Crime.

Rio’s crack scene evolved differently from São Paulo’s. While São Paulo has one main crackland in the downtown area, Rio may have up to 50 dotting its urban sprawl, according to Lidiane Malanquini, a project coordinator for social development organization Redes da Maré. Within Maré — a complex of several favelas — is one of the biggest cracklands in the city, with about 100 resident drug users.

But of all the rival criminal organizations fighting for control in Rio, only one allows cracklands to exist on its turf, Malanquini told InSight Crime.

That group is the Red Command (Comando Vermelho – CV), a powerful transnational organization with prison roots that has strong ties to the PCC. “Militias” — paramilitary groups made up of current and former members of the security forces — provide security for the cracklands, Malanquini added.

Both the PCC and CV exert a strong social control, effectively filling the void created by the absence of state authorities in these marginalized communities.

In downtown São Paulo, “you can’t rob, murder, be violent … only when the PCC tells you to,” said Gomes. Enforcing the “laws” established by the PCC are so-called “disciplines” (disciplinas), who often have links to the group’s leaders in prison.

“In Rio de Janeiro, this is called ‘the law of the favela,’” says Malanquini.

A number of factors explain how these criminal groups have been able to displace state power. In São Paulo, the “endemic” corruption within the police force is key. Gomes recounted how an anti-narcotic official who was a patient of his had told him that “everyone” in the area’s civil police force was cashing in by letting the illicit drug trade continue.

According to Malanquini, corruption in Rio involves high-ranking criminals. Any deal with the police is “not made by the armed youths in the Maré, it is a decision made by the big traffickers.”

At the same time, Brazil’s security forces lack the capacity or will to occupy these inner-city drug hubs. In São Paulo’s crackland, where the police are a constant presence, the 1,000 or more drug users pose a huge obstacle. The crack users are in a sense tied to their surroundings, not only consuming the drug but also using it as currency for anything from food and cigarettes to sex. Because the users are also peddling, it makes the real drug dealers harder to identify. And the addicts protect the streets from state forces.

“Usually drug users react to police with a lot of violence,” Gomes said.

In contrast, Malanquini explained that security forces in Rio have little desire to venture into cracklands in the first place.

“Their interest in the Maré is to find high-level traffickers … and seize drugs and weapons,” she said. The few crack rocks they might find in a crackland operation do not fit these criteria.

Gomes believes that to an extent, the state also knows it cannot wipe out cracklands in the space of a few years. Sporadic use of force by state agents will not suffice. “It’s a very social problem,” the psychologist said.

These drug hubs have become immensely profitable. Recently, it was revealed that a supposed homeless people’s charity in São Paulo called MSTS was actually a front for the PCC. The organization’s workplace was described by police as the “headquarters” of drug trafficking in central São Paulo’s crackland, and was used to store and distribute drugs and weapons.

Investigators estimated that this faction was making up to $1.2 million per month (3 to 4 million Brazilian reals) by selling around 10 kilograms of crack a day.

‘Independent Republic’ of the Bronx: Colombia

A mere 800 meters from Colombia’s presidential palace, Casa de Nariño, lie the remains of what was once Bogotá’s most important drug den — the “Bronx.”

In late May, authorities carried out an operation involving some 3,000 members of the security forces to dismantle the criminal stronghold where homeless people, tourists and party-goers would converge.

Footage of the Bronx operation in May 2016

The Bronx, which covers four city blocks, was dubbed “an independent republic of crime” by Bogotá Mayor Enrique Peñalosa. Within it, three main criminal groups — the “gancho mosco,” “gancho manguera,” and “gancho payaso” — ran a criminal system that included drug, arms and human trafficking as well as the sexual exploitation of minors.

The so-called “Sayayines” were the Bronx’s “army,” providing security for drug sales and other criminal activities such as prostitution and extortion. This group used extreme violence to maintain authority; it reportedly tortured, dismembered and dissolved victims’ bodies in acid. The Sayayines continue to operate throughout Bogotá, providing their services to the city’s various drug organizations.

Police would rarely venture into the Bronx, and some who did were kidnapped or killed. Nevertheless, the Bronx was able to thrive as a drug hub because the criminals who ran it had up to 50 police officers on their payroll, judicial sources have said. Officers were allegedly paid to turn a blind eye to illicit activities, warn criminal groups of imminent security operations and refrain from searching the Bronx’s regular clients. Police witnesses have even accused former police station commander Gerardo Rivera, also known as “Verde 14,” of faking anti-narcotics operations and ordering agents to hide the extent of criminal activity in the Bronx.

The level of infiltration was so extensive and obvious that police agents were brought in from other parts of Colombia to carry out the operation in May. Authorities feared that local officers would leak information and thwart the massive raid, as had happened in the past.

At least 15 police agents involved in the Bronx’s activities have already been arrested this year, and another 30 or so are under investigation. Following the operation, an Attorney General’s Office representative said: “All of Colombia’s drug distribution centers are protected by the police.”

According to Bogotá’s Security Secretary Daniel Mejía, criminal operations in the Bronx were worth between $1 million and $2 million per month. Its drug trade alone was estimated at $33,000 to $50,000 per day, while an unexpected source of criminal profits was discovered in the hundreds of slot machines seized in the area. The army of Sayayines would also charge local businessmen extortion fees of $2 per day for their protection services.

Although the Bronx drug hub may have been suppressed, it continues to cause headaches for the local government. The Bronx is believed to have became Bogotá’s main criminal hub following the destruction of a zone called “Cartucho” in the late 1990s during Peñalosa’s first term as mayor. And just as criminal activity simply shifted locations then, there are signs that the same process is underway again.

Recently, hundreds of police agents have forced criminal groups out of other drug sale hubs that have popped up following the May operation in the Bronx.