After a long day of work in the highlands, a coordinator for several clandestine methamphetamine and fentanyl laboratories in the Mexican state of Sinaloa climbed to the top of a mountain to get a cell phone signal.

It was around nine o’clock at night, in early March. A few minutes after arriving, the coordinator received a call from an acquaintance in the city of Culiacán, the state capital. Also on the call was an InSight Crime team member.

This was the second time InSight Crime had spoken to this coordinator. Previously, he had explained that he worked for various drug production and trafficking networks associated with the Chapitos and Ismael Zambada García, alias “El Mayo,” two of the main factions of the Sinaloa Cartel. In addition to his administrative duties, the coordinator’s role involves maintaining contact with synthetic drug buyers abroad.

Amid interruptions due to a bad signal and motorcycle noises, he explained his take on trends in the international methamphetamine trafficking scene.

“The goal is to send crystal [methamphetamine] all over the world. That’s what’s happening,” he said.

He was referring to Mexican trafficking networks’ ambitions to expand their circle of clients beyond the United States in search of better prices. Several methamphetamine producers and wholesalers interviewed by InSight Crime over the past two years have also alluded to this aim.

Their efforts to try to get Mexican methamphetamine into new markets have attracted the attention of international authorities, particularly over the last decade. And in the last seven months, there have been record seizures in Europe and Asia.

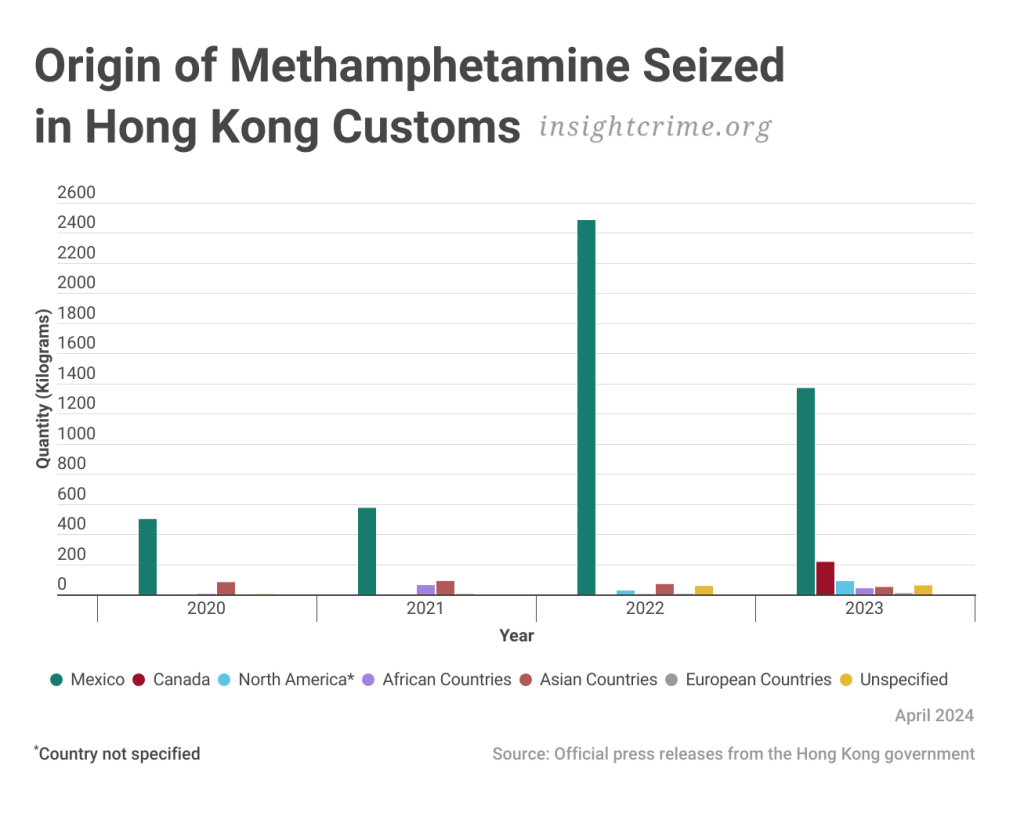

In early February, for example, Irish police seized half a ton of the drug in the port of Cork and linked the shipment to networks associated with the Sinaloa Cartel, according to press reports. Four months earlier, in October 2023, Hong Kong customs authorities made the largest seizure of solid methamphetamine in the island’s history, finding 1.1 tons from Mexico.

In Search of More Profitable Markets

Expanding into new markets is a strategic financial move. Production costs per kilogram of methamphetamine can be as high as $1,000, to which must be added transportation costs, bribes, and the occasional fees paid to criminal groups along the route, according to the coordinator and other methamphetamine producers interviewed by InSight Crime in Sinaloa and Michoacán.

Profits in Mexico and the United States are barely enough to cover this investment. On average, a kilogram of wholesale methamphetamine sells for $600 in Mexico and $5,000 in the United States, according to the same sources.

“We need to look for new markets to offset all the costs,” a methamphetamine producer in Michoacán told InSight Crime in December 2022.

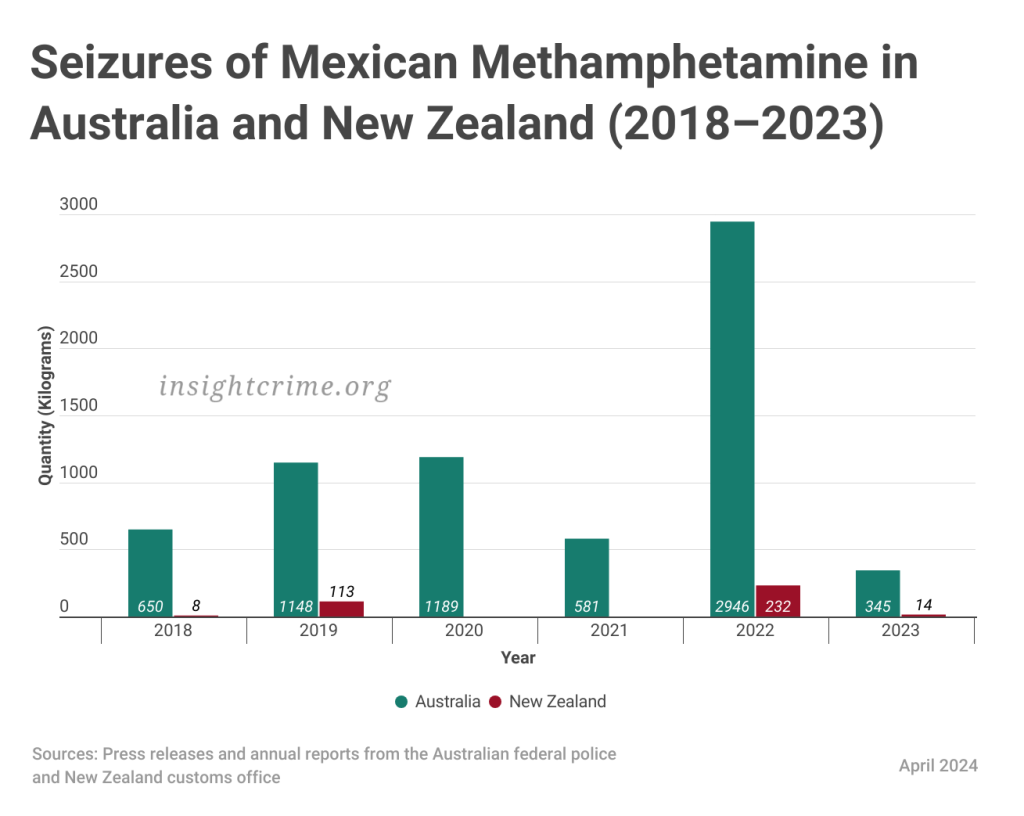

Europe and Oceania offer an opportunity for higher profits. Although transport costs increase, the same amount of methamphetamine can be worth an average of $20,000 in European countries and up to $190,000 in Australia and New Zealand, according to data from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA).

With the potential for such huge profits, Australian and New Zealand authorities have begun to see a significant flow of methamphetamine from Mexico since 2018.

“These [Mexican] organized crime groups are constantly targeting New Zealand … They are importing illicit drugs, establishing supply lines to domestic markets, and then moving their profits out of the country,” Greg Williams, director of the New Zealand Police’s national organized crime task force, said in a press release on February 13.

“Drugs in Australia get very high prices when compared to other markets … there’s a very clear incentive for these groups to take a more interested look,” Anthea McCarthy-Jones, an organized crime expert and senior lecturer at the University of New South Wales, told InSight Crime.

Methamphetamine Moves Through Major Ports Worldwide

The Sinaloa lab coordinator explained that methamphetamine shipments to Europe and Oceania are often sent via maritime or air trade routes, camouflaged among widely traded legal products.

In recent seizures, for example, Mexican traffickers have hidden methamphetamine in boxes of coconut water, steel, seashells, hydraulic presses, and even in boxes with Mexican government seals.

To minimize the risk of detection, traffickers often use ports and airports with a high flow of cargo. It is therefore not surprising that the European ports of Rotterdam, Valencia, Hamburg, and Cork, as well as the international airport of Amsterdam-Schipol, have detected large quantities of methamphetamine of Mexican origin in the past.

SEE ALSO: Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport Becoming Arrival Point for Mexican Drugs

The port of Hong Kong has also become a key point on the route to Asia and Oceania. It receives products from around the world, and almost all the shipping companies that connect the Mexican ports of Manzanillo and Lázaro Cárdenas — which are close to drug production zones — with Asia pass through that territory.

Since at least 2020, Hong Kong authorities have seen an increase in methamphetamine seizures. Mexico has been the most common source country for these shipments.

But routes are not always direct. The lab coordinator said that long and complicated routes can be useful to distract the authorities.

Recent journalistic investigations have supported this. In January 2024, for example, the Canadian media outlet the Vancouver Sun found that the port of Vancouver was used as a transshipment point to send methamphetamine from Mexico to Australia, via Canada.

Criminal Competition

Although they are expanding their international trade, the involvement of Mexican traffickers in the European and Oceanian drug markets is still in its early stages.

Unlike in the United States, where they have access to most of the market, in Europe and Oceania Mexican groups must collaborate and compete with various organizations from different countries that have established strong supply lines and customer relationships over the years.

Towards the end of the call, the Sinaloa lab coordinator explained that Mexican networks simply sell the drugs wholesale to various family clans or gangs on these continents, who then take care of regional distribution. He declined to name specific criminal organizations he was working with abroad.

This idea is in line with McCarthy-Jones’ research in Australia. She said that criminal organizations in the Golden Triangle, a center of drug production in Southeast Asia, continue to be the main suppliers of methamphetamine there.

“[Mexican criminal groups] are wholesalers,” she explained. “I think they probably are competing against each other. And I would imagine that the Mexicans are looking to increase their market share.”

According to McCarthy-Jones, Mexican traffickers have so far relied on brokers to make the connections with Australian and New Zealand distributors, meaning they maintain a certain distance. The brokers are often knowledgeable about the local scene and are responsible for navigating the logistics and making the right contacts on behalf of the Mexicans.

“They are essential in a protection and security sense … to protect your own organization against law enforcement efforts,” she added.

The situation is similar in Europe. While authorities have detected large seizures of Mexican methamphetamine, connections to European organizations also appear limited to the use of intermediaries or emissaries.

“There is a huge supply of methamphetamine directly from Mexico to Europe. We haven’t seen any big cases for a while,” Andrew Cunningham, director of drug markets, crime and supply reduction at EMCDDA told InSight Crime.

Cunningham added that the participation of Mexican organizations in European markets may vary by country. The greatest involvement has been seen in Spain, where the Beltran Leyva Organization (BLO) was associated with a 1.6 ton shipment of methamphetamine in 2019.

However, most of the shipments intercepted in Europe are presumably en route to other non-European countries, rather than destined for local consumption, according to a 2022 report by the EMCDDA and a joint report of the same year by Europol and the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA).

Meanwhile, local methamphetamine production and distribution appears to remain dominated by local criminal groups.

*Parker Asmann, Peter Appleby, and Douwe Den Held contributed to this article. Miguel Angel Vega contributed with field work.