The number of extortion cases recorded in Ecuador has skyrocketed over the past year, suggesting that the country’s fragmenting criminal gangs are seeking new sources of income.

Extortion in Ecuador rose by more than 65% between 2022 and November 2023 and by almost 400% since 2021, according to data that Ecuadorian police shared with InSight Crime.

The rise in cases has been accompanied by incidents of often brutal and indiscriminate violence. In one of the most recent examples, members of an unnamed criminal group launched a grenade at a school in the port city of Guayaquil at the start of December. It was the second violent attack against the school since it received a $10,000 extortion demand in October.

“If you don’t pay, they throw a bomb at you, they shoot you. And so, people are closing their businesses,” Juan Jaramillo, an Ecuadorian security expert and former police commander along the country’s northern border, told InSight Crime.

InSight Crime spoke to over a dozen security experts and police officials to explain what is driving Ecuador’s latest security crisis.

The Extortion Crisis

Ecuador’s police divide extortion into four categories: virtual, common, sexual, and vacuna, or vaccine — a term that originated in Colombia’s cattle country, where leftist guerrillas would regularly extort ranchers. Although different criminal dynamics contribute to each, a significant portion involves sophisticated organized crime operations.

Virtual extortion, which has seen the biggest rise in cases, is characterized by threatening phone calls or online messages that often originate from prisons, according to Ecuadorian police officials and security experts. The callers frequently identify themselves as members of a known criminal group, even if they are not connected to one.

Common extortion is what security officials define as “crimes of opportunity.” This can include things not commonly associated with extortion, such as express kidnappings, in which a person is seized and held for a short period of time while being forced to withdraw or transfer money to the kidnappers. Criminals also steal property, often motorcycles, then demand payment for its return.

Sexual extortion involves blackmailing the victim with intimate or sexual material. Sexual extortion is the only type that saw a statistical decrease over the last year. However, it is difficult to track with precision, given the sensitivity of the material in question.

A vacuna requires a victim to make periodic payments or face physical harm or property damage. It has grown by nearly a quarter over the last year.

While the level of organization behind virtual, common, or sexual extortion is not always clear, imposing vacunas requires coordination and territorial control and is the type of extortion most associated with Ecuador’s large criminal groups, authorities and experts told InSight Crime.

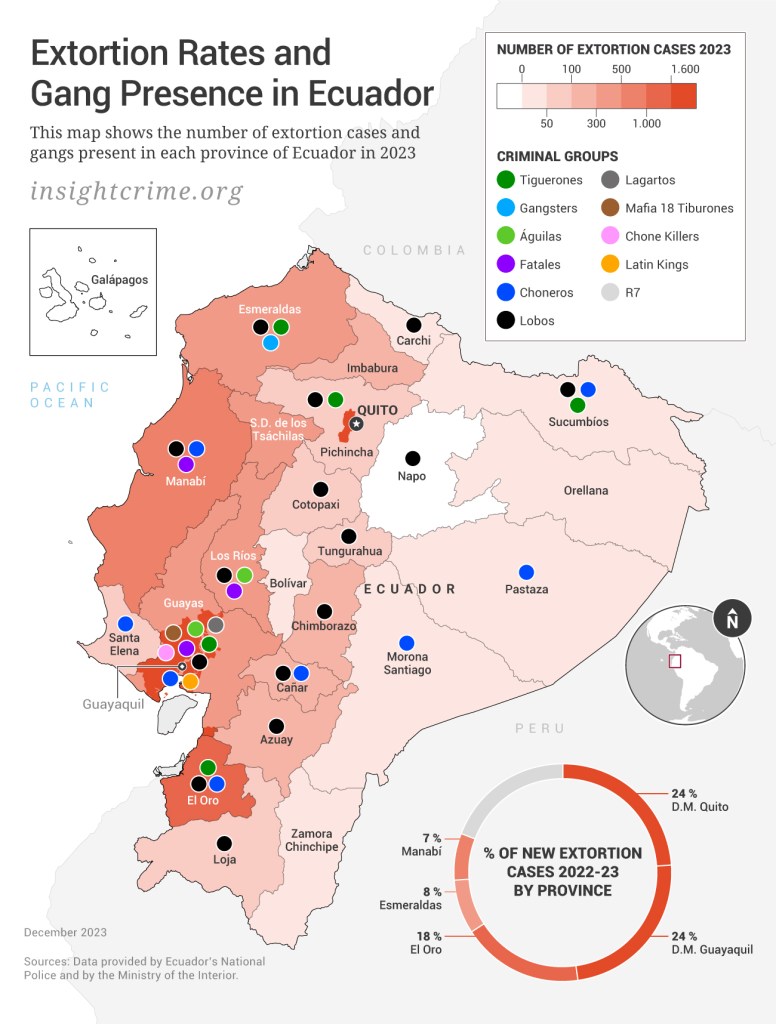

It is, therefore, not surprising that the majority of reported vacuna cases come from territories controlled by large drug-trafficking groups, including the Choneros, Lobos, and Tiguerones.

“Historically, these organizations were dedicated to drug trafficking, not extortion,” Renato Rivera-Rhon, coordinator of Ecuador’s Organized Crime Observatory (Observatorio Ecuatoriano de Crimen Organizado – OECO), told InSight Crime. “But it is becoming a new market that these same organizations are beginning to specialize in.”

SEE ALSO: The Rise and Fall of the Choneros, Ecuador’s Drug Trafficking Opportunists

Vacunas have hit Ecuador’s businesses hard, with reports of mass closures of restaurants, bars, and other companies as owners struggle to pay.

The criminals appear to primarily target medium and small businesses, including the distributors and logistics companies serving large multinationals, experts and security officials told InSight Crime.

In some provinces, their operations have become systematic. The Tiguerones and Lobos, for instance, use stickers to mark transport vehicles that have paid, said a police source who spoke to InSight Crime on the condition of anonymity.

Gang Fragmentation

Ecuador’s largest gangs ballooned by feeding off cocaine profits. Chief among these was the Choneros gang, a major service provider for transnational drug trafficking networks. But after the murder of the group’s leader in 2020, the Choneros splintered into warring factions and came under attack by a coalition of smaller groups previously under their control.

Some of these smaller factions, like the Lobos and Tiguerones, have become sophisticated drug trafficking outfits in their own right. But many were left without the connections, infrastructure, or know-how to continue trafficking drugs. These groups appear to be turning to extortion to finance ongoing gang wars, security experts and officials told InSight Crime.

“That’s where it all started: we sounded the alarms, warning that with each fragmented gang, there would be criminals who would keep committing crimes on the street. That’s what we’re seeing now with extortion,” Major Hector Javier Franco, a coordination and operations specialist with Ecuador’s anti-extortion and anti-kidnapping police unit, told InSight Crime.

The ongoing cycle of fragmentation — marked by betrayals, assassinations, and prison massacres — leaves an ever-growing number of small gangs to fight for control of territory and criminal economies, suggesting that the number of extortion cases is only likely to grow.

“Crime mutates, crime adapts,” Max Campos, an Ecuadorian security analyst and reserve police colonel, told InSight Crime, referring to drug trafficking groups’ turning to extortion.

Changing Cocaine Markets?

In addition to fragmentation, some security experts and police officials consulted by InSight Crime claimed that shifts in drug trafficking dynamics have left gangs that focus solely on moving cocaine through Ecuador with reduced profits, contributing to the increase in extortion. On this point, however, opinions are split.

According to police officials, improved interdiction efforts have made trafficking cocaine through Ecuador more challenging, more expensive, and, ultimately, less profitable. This, they said, has driven further gang fragmentation and fueled extortion.

“To survive, they have to dedicate themselves to [extortion],” Franco told InSight Crime.

Other experts, however, say that the drop is more about the dynamics of the cocaine trade than any official crackdown. Specifically, groups that worked to help traffic cocaine to the United States are being sidelined because the volume of cocaine shipped through Ecuador to that country is dropping. This has pushed them into other criminal markets, such as extortion, the experts said.

Ecuador’s drug seizure data seems to back up this assertion. The overall volume of cocaine seizures in Ecuador destined for the United States has fallen dramatically in the past two years, according to data shared with InSight Crime by Ecuadorian police.

In contrast, criminal groups helping to move cocaine to Europe are profiting as much or more than before as the flow through Ecuador shifts increasingly towards transatlantic routes.

According to Fredy Rivera Velez, a security and strategic studies professor in Ecuador, close to 70% of the cocaine exported from Ecuador is now destined for Europe.

“Today’s disputes are about the reorientation of cocaine exports — about control of the ports, but above all, the European links,” he told InSight Crime.

An Intractable Problem

Ecuador’s growing insecurity and violence have also started a self-perpetuating criminal cycle that may be difficult to reverse. Extortion is both a result and a driving force of that cycle.

Evidence of this is a resurgence in child recruitment over the last year, which may also be contributing to the rise in extortion.

Poverty, inequality, and repeated cycles of violence help drive recruitment, especially among vulnerable youths looking for a sense of social belonging or safety amid the chaos. As organized crime becomes more sophisticated and prevalent, these youths have ready access to weapons, training, and operational models. And while they are contracted by larger criminal groups, this work may be sporadic. To fill in the gaps, they turn to easier criminal activities such as extortion, especially common or virtual extortion.

SEE ALSO: The School of Terror: Inside a Jalisco Cartel Training Camp in Mexico

“They have access to information and, above all, control of territory,” General Freddy Sarzosa Guerra, head of the criminal investigation unit in Ecuador’s Police, told InSight Crime. “Extortion does not need much planning, and it is an immediate source of income.”

Extortion itself is also a self-perpetuating criminal economy. Increased extortion by organized crime creates an environment of fear that makes it easy for small-time criminals to virtually extort victims who would have previously ignored their calls or messages.

“Before, if you said, ‘I am a member of the Choneros,’ people would not have paid any attention; people would have ignored your call,” Rivera told InSight Crime. “Now, a call like that generates an instant feeling of fear.”