With record shark fin seizures continuing across Latin America, legislative efforts to protect sharks are being impeded by a lack of resources and the large criminal profits being generated.

Panama netted its largest-ever shark fin seizure this month, nabbing 6.79 tons of shark fins on July 13 near Capira, a town southwest of Panama City. Five Panamanian citizens were arrested, as well as one Chinese woman, who allegedly bankrolled the initiative.

The record-setting seizure came months after the country used its role as host of the November 2022 World Wildlife Conference to advance efforts to add the blue shark, requiem shark, and hammerhead shark to the list of species protected under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES).

The Panama seizure also followed the discovery of the world’s largest-ever shipment of illegal shark fins. The consignment seized in Brazil in June amounted to nearly 29 tons and was put together by two export companies, which had used legal permits for other species to illegally collect the fins. Environmental authorities estimate that around 10,000 blue sharks and short-fin mako sharks had been killed for this shipment.

Both species had been added to Brazil’s endangered species list a month earlier.

SEE ALSO: Plundered Oceans: IUU Fishing in Central American and Caribbean Waters

Peru is the largest exporter of shark fins in the world, with the vast majority of its catch headed to Asia. A hefty portion of these exports is illegal. From April 2017 to October 2021, over 150 tons of shark fins were exported to China, Singapore, and Vietnam, thanks to illicit permits handed out by complicit Peruvian officials, according to a recent Mongabay investigation.

This has made Peru very resistant to implementing the protections recommended by Panama, making it one of the only holdouts in Latin America.

InSight Crime Analysis

While the Panama example showed there is a real desire to take action against the shark fin trade, concerned nations must reckon with corrupt officials, a lack of capacity, and the sheer profits at play.

“Panama’s Aquatic Resources Authority (Autoridad de Recursos Acuáticos de Panamá – ARAP) does not have the finances or personnel to effectively enforce…fishing rules in our waters, much less the international fishing fleet,” Luisa Araúz, an environmental rights lawyer in Panama, told InSight Crime. “The state apparatus is not ready to face the magnitude of the problem.”

SEE ALSO: Plundered Oceans: IUU Fishing in South American Seas

While Panama is currently discussing a bill that plans to restore and protect shark populations in Panamanian waters, the country has still not banned shark fishing and the export of shark fins.

Elsewhere, legislative and judicial efforts also seem positive but may lack teeth.

In great fanfare, Peru convicted two shark traffickers to four and a half years in prison in February 2022. They had been arrested in 2018 in possession of 1.8 tons of fins from six species of shark, which they were going to sell to a seafood company.

“This is a major success for Peru, and it is crucial that judges have begun to understand that we’re dealing with species that play a critical role in our oceans,” César Ipenza, a lawyer specializing in environmental affairs, told InSight Crime at the time.

This was the first time the country had ever sentenced anyone for shark finning. But it took four years for the case to be completed, and there have been no convictions since.

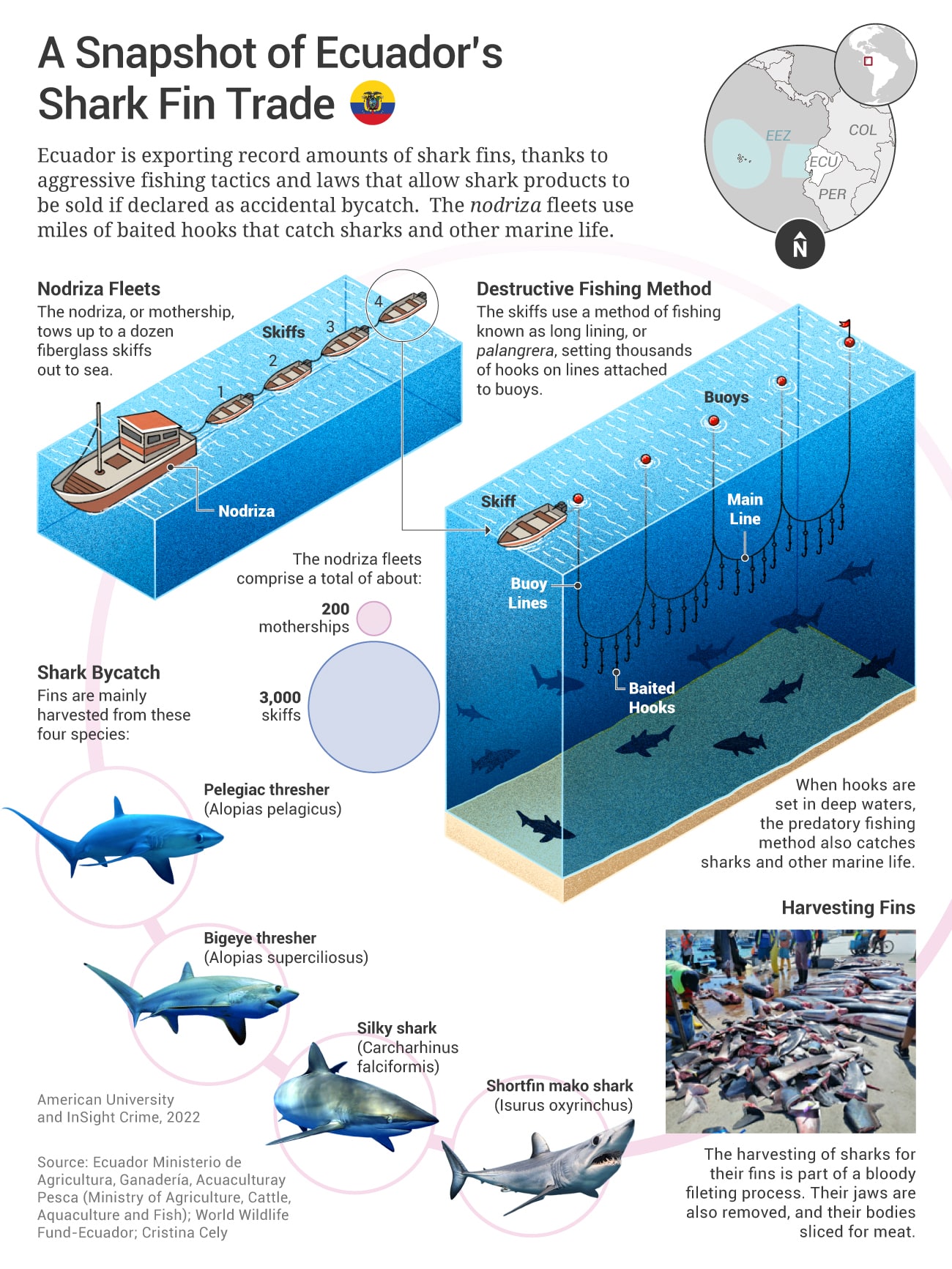

Besides being the largest exporter, Peru also receives significant shark fin exports from Ecuador. Despite the country banning shark finning in 2004, an InSight Crime investigation found that Ecuador exported just under 800 tons of shark fins to Peru from January 2017 to June 2022.

While Peruvian customs are being more cautious to ensure that illegal shark fins are not being mixed in with legal catch, there are other ways to smuggle the fins across the border, according to Alicia Kuroiwa, director of threatened habitats and species for Oceana in Peru.

“There are over 200 illegal crossing points between Peru and Ecuador, and [the fins] go through there, with all the contraband,” said Kuroiwa. “They come in land through those illegal paths and by sea, transferred from small vessels.”

She added that illegal fins are also being masked among frozen fish, which authorities are more reticent to inspect, given the risk of ruining the entire shipment should it thaw.

Finally, Brazil catches about 5,000 tons of shark meat a year, mostly from protected blue sharks and hammerhead sharks. Additionally, it imports 17,000 tons of shark meat, including from China, Portugal, and neighbors like Uruguay.

Brazil does not emit legal permits for shark fishing, and only bycatch declared as accidental can be used.

“In practical terms, huge quantities of shark are fished and landed using this approach. Any boat can bring in tons of shark if they call it bycatch and say that the target species for which they have the license was not found,” Patricia Charvet, a shark researcher at the Federal University of Ceará, told National Geographic.