Synthetic drugs are increasingly rewriting the rules of Latin America’s drug trade, as new markets, routes, and substances challenge the traditional dominance of plant-based narcotics.

Mexican methamphetamine is being exported in bulk to the Asia-Pacific region, fentanyl is being added to stimulants in South America, and ecstasy flows from Europe to the Southern Cone are soaring.

Meanwhile, ketamine is becoming a cheap mixer in drug cocktails like “tusi” and hallucinogenic new psychoactive substances (NPS) keep popping up across the continent. The result is a flourishing market that is drawing the attention of both Latin America’s governments and its drug traffickers.

To better understand these issues, InSight Crime spoke to Martin Raithelhuber, a synthetic drugs expert and International Coordinator for the Global Synthetics Monitoring: Analyses, Reporting and Trends (SMART) Programme at the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).

InSight Crime (IC): Could you start by telling us a bit about the Global SMART program’s work in the region?

Martin Raithelhuber (MR): In 2011, Global SMART began activities to raise awareness of synthetic drugs in Latin America and the Caribbean. We began mainly with regional activities — workshops, a report — that focused on knowledge building rather than specific country capacity-building.

That has changed over time, though. We are currently working with law enforcement on improving detection capabilities, for example, by delivering handheld electronic drug detection devices. We have now delivered such devices to 20 countries in the region. As importantly, we’re also providing training to increase the knowledge of what is out there.

Of course, every law enforcement officer in the region knows about cocaine, marijuana, and probably heroin. But it often stops there. They would not necessarily be aware that methamphetamine plays a significant role in the region or know much about ecstasy or synthetic drug pills containing NPS.

There is even less knowledge when we go into more specific NPS — the synthetic cannabinoids, the stimulants, the cathinones, let alone the synthetic opioids like fentanyl or carfentanyl.

We therefore also offer training to forensic laboratories. We offer manuals with methods on how to analyze the substances in the laboratory. And more recently, we’ve had a strong focus on promoting the establishment of early warning systems for synthetic drugs.

IC: Let’s look at specific drugs. Mexico and, to a much lesser extent, Guatemala, are the manufacturing and trafficking hubs for methamphetamine Latin America. Do you think this could expand to other countries?

MR: Within Central America, it is still rare to make significant methamphetamine seizures. They tend to occur in countries where there is already illicit manufacture of methamphetamine, such as in Guatemala. However, there is a suspicion that methamphetamine production is spreading further south, for example, into Honduras. That is based on reports of precursor seizures. These precursors could also be meant for Mexico, so it’s important to say this is just a suspicion. But looking at the overall trends, we see a southward movement for illicit methamphetamine manufacture.

IC: In terms of illegal methamphetamine manufacturing in Mexico, what do you think are the main drivers of exportation not just to North America, but now to Europe and to the Asia Pacific region?

MR: I can’t read the minds of drug traffickers. However, looking at the trends, we see that because of the move from ephedrine-based processes to P2P-based processes, Mexican methamphetamine producers can rely on a much broader range of precursor chemicals, many of which are not under international or national control.

That might mean precursors are more readily available and perhaps cheaper than before. One reason we think that is because in the United States, methamphetamine prices have fallen quite significantly in recent years, while purity continues to be very high. I mean, very high. We believe that means production costs are down, but because there is so much supply, so are the profit margins.

Hence, traffickers have a few options. One is to increase consumption, but there is always a limit to that. Another is to expand their geographic markets by looking for new places to supply. And along with North America, the world’s other big regions of methamphetamine consumption are Southeast Asia and Oceania — mainly Australia and to a lesser extent, New Zealand.

So from a marketing perspective, it’s logical to say ‘I have a product which I can produce very cheaply, my main market is becoming somewhat saturated, so what other markets are there’? And clearly that’s Southeast Asia and the Pacific.

IC: You mentioned the high purity of Mexican methamphetamine. How do you think it compares to meth produced in other hotspots, like Afghanistan or Southeast Asia’s Golden Triangle?

MR: It’s hard to compare. With methamphetamine, there are two elements to consider: firstly, the purity, and secondly, the concentration of d-methamphetamine — the desired and stronger isomer — versus l-methamphetamine.

The information we have from laboratories in Southeast Asia is that both purity and concentration of d-methamphetamine in the methamphetamine produced in the Golden Triangle is very high. That’s also true for Mexican methamphetamine.

Now, for the Afghan methamphetamine, we are still working on the basis of a very small number of samples analyzed. But the samples were also of good quality.

IC: How do you think ecstasy trafficking to Latin America has changed in recent years?

MR: There are two developments I would like to mention: one is trafficking by post or courier, which is one of the main routes of MDMA trafficking into the region, particularly to Central America and the Caribbean. We are not talking kilos here, just a couple of hundred tablets at a time. More recently, countries in the Southern Cone, like Uruguay for example, have also made larger seizures — hundreds of grams or maybe a kilo or so.

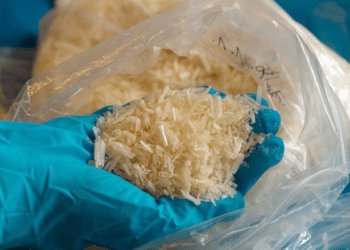

And that also includes crystalline MDMA now, which can have dangerously high purity. Pills or tablets are still much more common, though; these are mostly smuggled from Europe and reprocessed or “tabletted” locally to increase the yields.

IC: In May and June, Chile seized nearly 475,000 ecstasy pills on ships coming from Dutch and Belgian ports. Do you think those kind of large-scale MDMA shipments are increasing?

MR: I would definitely agree that these large amounts are uncommon in South America. Having more than a couple of thousand pills was really rare in the past. Will we see this more often? That partly depends on the absorption capacity of South America’s markets. I mean, ecstasy is typically consumed by a very specific group of the population. So that somewhat limits the opportunities for market expansion.

What is certainly true though is that MDMA manufacture in Europe is large-scale and it can churn out huge amounts of very high quality MDMA. And that’s another key development in Latin America’s synthetic drug market. Dutch criminals have found ways to produce large amounts of MDMA and they’re looking for new markets.

IC: Has domestic MDMA manufacture been witnessed in Latin America and what factors could help or limit its expansion?

MR: In 2020, we reported the emergence of local synthesis in southern Brazil, where police busted several laboratories synthesizing ecstasy. It probably wasn’t MDMA though, but MDA. I am not aware of other reports of synthesis of ecstasy type substances in the whole region, but ecstasy labs that retablet or dilute imported drugs remain common.

SEE ALSO: Brazil’s Santa Catarina Becoming Country’s MDMA Hub

As for opportunities for expansion, given the fact that there is very large-scale MDMA manufacture in Europe that is increasingly being shipped over, I think it will probably be quite hard to establish economically viable domestic synthesis facilities.

IC: Moving then to opioids. In February 2022, a series of cocaine doses laced with carfentanyl killed several dozen people in Argentina. In your opinion, will these contamination incidents become increasingly common?

MR: It’s really hard to know. I think there could be underreporting in Latin America, in which cocaine, heroin or other drugs are already being laced with fentanyl or other synthetic opiates, but because no one is brought to a hospital the drug is never detected. I think the Argentina incident tells us that we need to pay more attention to this and better test common drugs in the region, like cocaine.

The US opioid crisis came about through a very specific combination of factors, some of which were also present to a lesser extent in Canada. I think a lot of these factors are not present in Latin America, so I don’t expect the same development here. The biggest enabling factor in Latin America — which was also seen in the US — is the easy availability of medicines without having the necessary prescription. That said, overall prevalence of opioids in Latin America is extremely low. There’s just not a lot of non-medical opioid use among the population.

IC: Going on to ketamine. There has been an apparent increase in seizures across certain countries, like Costa Rica and Chile. Do you think ketamine could ever become as popular in Latin America as it is in parts of Southeast Asia and Europe?

MR: I think ketamine sold as ketamine is not particularly popular in Latin America. There are more cases in which ketamine is sold under the name of the popular drug cocktail “tusi,” a.k.a. “tucibi” or “2C-B.” The latter obviously refers to a completely different substance, but it doesn’t matter. It is the brand name that counts and by using that brand name, they’re selling ketamine mixed with other substances.

Most interestingly, multi-kilogram seizures of tusi have been made in Europe, particularly in Spain but also in the UK and most recently in Austria. This is very unusual for Europe, but such cases have increased over the last few months.

IC: Let’s finish with NPS. The World Drug Report 2022 states that South America has a relatively high proportion of hallucinogenic NPS. Can you tell us a bit more about that?

MR: The overall number of NPS in South America is much lower than in Europe or in the US, but the proportion of hallucinogenic NPS is higher than in both. It’s a very consistent regional peculiarity, which we have observed since at least 2013. The plant-based hallucinogenic NPS tend to be locally grown: for example, Angel’s Trumpet or the Ayahuasca brew.

Many of the synthetic NPS hallucinogens were originally created in Asia and particularly in China. However, of the ones that make it to Latin America, a lot of the customization, packaging, and transshipment seems to occur in Europe, particularly in Spain.

*This interview has been edited for length and clarity.