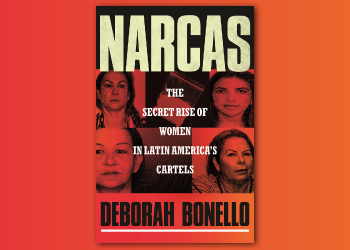

A new book by journalist Deborah Bonello examines the roles women play in organized crime and argues that their participation in criminal activities deserves further study.

In Narcas: The Secret Rise of Women in Latin America’s Cartels, Bonello, a former editor and investigator for InSight Crime, explores how women participate in the region’s criminal landscape, the common misconceptions about their involvement with criminal groups, how women in crime are represented by the media, and the relationships they have.

The book tells the stories of several women who rose through the violent world of organized crime. It starts with criminal clan leader Digna Valle, who led the Valle crime family in Honduras from behind the scenes. Marixa Lemus, who was part of the Lemus drug trafficking and political clan in Guatemala, became known as Guatemala’s “female Chapo” for escaping prison multiple times. Narcas also looks at prolific drug traffickers like the Mexican Luz Irene Fajardo Campos, Colombian Yaneth Vergara Hernández, and Guatemalan Sebastiana Cottón, as well as infamous money launderer Marllory Chacón. In each case, Bonello details how these women have cultivated power in distinct ways — often using gendered assumptions to pass under the radar — and made names for themselves in Latin America’s criminal underworld.

InSight Crime spoke with Bonello about her coverage of women in Latin America’s criminal groups and how telling their stories adds to our understanding of criminal dynamics.

InSight Crime (IC): What was the most interesting story you told in this book? Why did it resonate with you?

Deborah Bonello (DB): It’s hard to choose because as soon as I started looking into them, my mind was blown by how their stories are very different from the mainstream narratives that we see about men. With Digna Valle, I went to her hometown in Honduras, and it was hard to get to the bottom of how violent she was. The women who received me adored her and were big supporters of her, whereas asylum seekers in the US told me that she had been sending out hits on people, but Digna was not prosecuted or convicted for violent crimes. Marixa Lemus was also fascinating, and Luz Irene Fajardo Campos ran her trafficking ring out of Sinaloa until she was arrested in Colombia.

The view of women in organized crime has largely been through the lens of women as victims, which is of course important, but I think it is related to the way that women are perceived and the way that our agency is taken away. With Luz and with a lot of the women that I covered, I came to the idea that maybe the cartels are much more aligned with the business values of legal business organizations than they are with this misogyny and hyper-violence that’s been associated with them. That’s not to say that they don’t perpetrate gross levels of violence, especially the MS13 in El Salvador. But at the same time, it does seem to me that if male leadership sees that women can perform tasks efficiently to the level of men or above, they tend to give them a job or they tend to work with them. When you see people like Digna working with her brothers and Sebastiana Cottón taking over from her husband, you can see that they are players, and the cartels work with them.

IC: In your book, you write about the narratives that have been created about women’s relationships and involvement with organized crime. What are the common misconceptions about women in organized crime?

DB: It’s deeply uncomfortable for societies, and especially Latino societies, to see women becoming empowered and making decisions in industries that are so viscerally violent and have such an effect on public health. It’s more comfortable to think that those women were forced into it than that they decided to stay in them.

SEE ALSO: Women and Organized Crime in Latin America: Beyond Victims and Victimizers

I think the truth of these women adds to our understanding of how organized crime works. Women within families and marriages are constantly powerhouses. As historian Elaine Kerry once said to me, they’re never just standing at the stove stirring the sauce. Women have tremendous political and social influence within the family, and the idea that they’re not influencing business decisions, they’re not controlling the men around them in some way, and they’re not also absorbed in this [criminal] culture is absurd.

IC: What do the women in your book have in common? How do they break the common archetypes usually used to describe women involved in organized crime?

DB: A lot of the women in the book — for example, Marixa, Sebastiana, Digna, and to a certain extent Yaneth and Luz — were born into environments where the drug trade was very prevalent. The profits were very available, and the bar to enter was low. In places like San Marcos, Guatemala and Copan, Honduras, where Digna was based, when cocaine started flowing up from Colombia in the 80s, it’s like opportunity knocked. A lot of those women share geographical opportunities and socioeconomic factors — the need to support their families, for example — so that [becoming involved in organized crime] made sense for them.

But you can’t explain it away just like that. Someone like Marllory [from an educated middle-class family] had other opportunities available to her, as did Luz Fajardo, who had a law degree. And then, you see people like Guadalupe Fernández [a Mexican drug trafficker linked to the Sinaloa Cartel] and Yaneth, who spent 30 or 40 years in the drug business. We have to understand that they are using their agency and they are making choices, but they’re still doing that in a limited environment.

Organized crime is never the only option, but certainly, in the countries I covered, the options are migration or getting some low-paying job. It’s very difficult if you’re born into the working class, which a lot of women are, especially the rural working class. It’s very difficult to even conceive yourself as becoming part of the business and political elite in your country. Organized crime provides job opportunities and empowerment and status for women and men who don’t see other roads to that.

IC: What is the relationship women involved in organized crime have with violence? Can we gain some understanding of their actions by using this analytical lens?

DB: As women, we are socialized to steer away from violence. Violence is a daily characteristic of life in rural Central America and Mexico. Those women were already exposed to violence, and the management of violence is a business strategy — it is one of the most powerful currencies in organized crime. Whether it’s extortion, whether it’s doing deals, or if someone’s threatening to harm you or harm your family, burn down your business, it’s difficult to resist or defend yourself. Most of the women were used to and tolerant of the presence of violence, even if they weren’t delegating violence or doing it themselves. For example, asylum seekers told me that Digna was sending out hits on people who she found out were informing on them, but she also tolerated and aided and abetted the violence of her brothers. For a lot of these women, having experienced the sharp end of violence themselves, maybe that jump was easier. This recognition that if they didn’t defend themselves, no one else was going to.

A lot of these women accept that that is how business is done. Women are very adaptable. They have their own powers and their own ways of arranging things the way that they want, but there’s so little social mobility and opportunities for them that, when they see an opening, they adapt. And [violence] becomes business; it’s a way of furthering and protecting their business interests. The interesting thing about the way that it’s perceived in the world is that there’s a moral and ethical weight to violence, and that’s important. But sometimes these women, just like the men who use it — especially if they’re delegating and they’re not pulling the trigger themselves — they rationalize it as a business strategy.

IC: How can we dive further into the stories of women in organized crime without falling into the victim/perpetrator categories?

DB: I think our obsession with victim versus victimizer has to do with moral judgment about blame. We need to be a little bit less categorical, and moving away from binary concepts of good and bad and victim and victimizer is helping us to better understand those worlds.

It’s important to show that a lot of perpetrators of violence have been victims of violence themselves, and have been exposed to violence themselves, and that’s very much the case for a lot of women. We must understand the whole picture, not just the experience of the victims, but also why that violence is taking place, and how [criminal] organizations are run.

The key lies with the women themselves, but I think women struggle to see themselves as empowered, and they struggle to own their role in [criminal] organizations because of the cultural and gender understandings that they have of the world around them.

Generally, with men, you see this cabrón identity. Women are also capable of that: Marixa in Guatemala was certainly owning that. But because of the world that we are emerging from as women, it’s hard for women to see themselves in the same way that men see themselves in those industries.

IC: How do women’s relationships shape the way organized crime works?

DB: The relationships between women are incredibly underestimated. We go into looking at criminal organizations with the lens that men are in charge, and if there’s a woman, she’s the seductress and she’s manipulating them that way. But power comes in so many forms and works in so many ways. Griselda Blanco was an interesting example: she was a mentor to Pablo Escobar, and the most famous female drug trafficker there ever was. She had these men and women all around her and the way that she managed them and controlled them to her advantage, shows she understood sexual dynamics and how men and women moved, and it’s much more fascinating than these binary ideas of “woman seduces man.”

SEE ALSO: Leadership Role of Women Often Overlooked in Mexico’s Organized Crime Landscape

It’s very difficult to pigeonhole the way that women behave in organized crime compared to men. I saw all types of women. it varied so much in terms of their personalities, their life experience, and how they’d been treated by men and women in the past. A lot of the women that I featured had been victims of violence and inter-marital abuse, so they’re coming from that position, too, which does not lead them towards naturally trusting and embracing some of the men in their lives. The possibilities are endless, but I think it is necessary to open the conversation up.

IC: Why have the stories of the women you present in your book been minimized or played down? Is it a direct consequence of the role that traditional gender stereotypes play in our understanding of organized crime?

I think the other important thing that I wanted to dispel with the book is that there has been this minimization of women because they take over from their husbands or they’re married to these guys. But organized crime is essentially clan based in Latin America, so why would we minimize women for coming into the business through their families and not men?

Gender stereotypes play a role. For certain criminal organizations, they don’t particularly want the female leadership to be visible because they feel like that compromises the brute male violence and power that’s so necessary to get business done. I do think that’s changing slower in Latin America than it is in the US and Europe to a certain extent. But it’s happening.

We are in an age where we’re more willing to question these kinds of fundamental assumptions on gender. As women are more active in the economic world and the political world, and with organized crime, we have to approach it in the same way that we analyze business and the nuances of these other institutions and dynamics that we look at in society.

*This interview has been edited for clarity and fluidity.