Listen to this article

Over Carnival weekend, as families crowded into Maracaibo’s small, air-conditioned shops, gunmen got off their motorbikes, entered a butcher’s shop, and without uttering a word, indiscriminately fired into the holiday crowd, wounding three people.

Less than two hours later, the violent scene played out again, this time in a small supermarket. The shooters left five bystanders wounded.

The two near-simultaneous attacks, just seven kilometers apart, were both motivated by extortion but had nothing to do with each other.

Maracaibo is the formerly bustling metropolitan capital of Zulia, Venezuela’s most populous state. Once flush with oil money, the city still holds importance as the gate between the northwestern border state of Zulia and the rest of Venezuela. But the Carnival weekend celebrations had been a rare show of liveliness in the capital’s streets, which today have a general feel of abandonment.

For weeks, coverage of the attacks dominated the news there, following a hunt for the perpetrators as Zulia’s political leaders issued calls to action and announced a flurry of security strategies and commissions.

This was a rare moment of outrage in a state where violence has become commonplace. But it was not always this way.

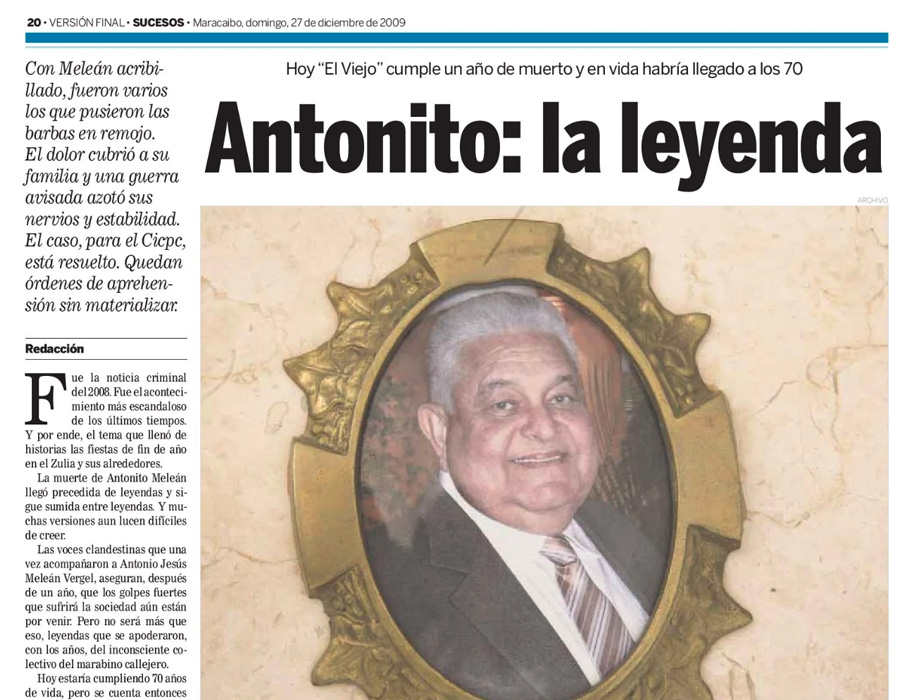

Until 2008, the state’s underworld was far more peaceful, dominated by one mafia godfather straight out of Hollywood — Antonio Jesús Meleán Vergel, alias “Antonito” — and the Meleán clan.

His death would shatter this peace.

The crumbling of the Meleán criminal empire coincided with Zulia’s slide into economic, social, and political collapse, forging a brutal and chaotic criminal class, whose extortion practices are devouring the state’s remaining legal businesses.

Over the past two years, InSight Crime has spoken with dozens of former and active security and political officials, residents, and experts to better understand Zulia’s complex criminal evolution.

Antonito Meleán and the Gentleman Mafia

Antonito and his family had ruled Zulia’s underworld since the 1980s.

Longtime residents of Zulia remember Antonito as a “gentleman mafioso” who controlled a patchwork of smaller gangs, which operated with his permission and followed his rules.

For his part, Antonito kept order in Zulia’s underworld — presiding like a judge over his mafia, resolving disputes between gang members, and keeping the peace according to his code.

“He was a real Vito Corleone. He had a historic level of control, and he was decent, polite, and kind. People respected him, and he kept a low profile. But if there were problems that the government didn’t solve, he served as a mediator to solve them,” a former Zulia politician, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, told InSight Crime.

Antonito’s reach was such that even local and regional politicians met with him to discuss the running of their municipalities.

“There were criminal groups in Zulia back then with which the government had to negotiate,” Juan Pablo Guanipa, an opposition politician and Zulia’s former governor-elect, said when asked about Antonito.

Antonito also sought to shield civilians from Zulia’s underworld, tolerating violence only as a last resort and forbidding outright the killing of women and children.

SEE ALSO: The Meleán News and Profile

Information on extortion during the Meleán era is scarce, but sources told InSight Crime that family-run shops were off limits and that urban gangs under Meleán control mostly engaged in car theft and, to a lesser extent, robbery and kidnapping.

Targets for these criminal economies were plentiful. Zulia’s booming oil economy acted as an engine for supporting industries that provided goods and services to well-paid oil employees: clothing stores, movie theaters, restaurants, and fishermen, among others.

But 2008 marked a turning point — both for Zulia as a whole and Antonito. The aging don began to lose his grip on his criminal empire.

The then-mayor of the state capital, Maracaibo, accused Antonito of being behind the murder of a student leader, publicly challenging the boss’ reputation as a well-respected businessman and rancher.

Antonito retaliated by penning an open letter accusing the mayor of corruption. But the political drama never had time to play out, as shortly after, Antonito’s own people turned on him. According to local newspaper Versión Final, which chronicled the story, the open letter would be the last Antonito ever wrote.

On December 27, 2008, Antonito was gunned down outside a barbershop. It was the eve of his 70th birthday. Authorities accused Daniel David Leal Prieto, alias “Danielito,” a young gang leader who described Antonito as a father figure and vehemently denied any involvement in his death.

The prevailing theory is that Antonito’s murder was part of a criminal coup, led by one subordinate faction of the Meleán in an attempt to take over the family’s empire.

It failed.

A Feeding Frenzy – the Breakdown of Order in Zulia’s Underworld

In the wake of Antonito’s death, neither his family nor the myriad of smaller gangs previously under his rule could achieve dominance. A chaotic war broke out as several gangs tried to fill the vacuum.

Nelson Meleán, Antonito’s brother, inherited a crime clan under siege. Within two years of Antonito’s death, Nelson had survived three attempts on his life. The third came in 2010 as he lay in a hospital recovering from a previous failed hit. Six gunmen stormed an intensive care unit and tried to shoot their way into Nelson’s room.

While the family members and bodyguards that stood vigil by his bedside were able to fight off the attackers, the assault left Nelson’s youngest son, his cousin, a friend, and two bodyguards dead, in addition to one of the assassins.

They were far from the only victims of the campaign against the Meleán. It was, as one Meleán widow told Venezuelan news media in 2011, “a concerted effort to finish off the Meleán family.”

Nelson was finally killed in 2012 in the coastal Colombian town of Santa Marta. By that time, at least 18 other members of Antonito’s family and close inner circle had been killed in the carnage.

Suspects were plentiful. One gang, known as the Pulgas, continued their hunt for the Meleán, even after their leader Danielito — Antonito’s alleged assassin — was killed in prison. Wilmer Matos, a longtime Meleán rival, headed up another network in the strategically important municipality of Miranda. A gangster named John Wade drove the Meleán out of the fishing town of La Cañada de Urdaneta.

These new bosses, including Nelson Meleán himself, saw no reason to keep up the gentleman mafioso reputation. They turned away from Antonito’s model of protecting communities and did not hesitate to employ violence against the growing number of extortion victims when they refused to pay.

“The day [Antonito] died… the mafia itself started to kill people. There was no longer one ‘chosen mafia,’ there were two and then three,” a former security official in the Zulia municipality of Miranda explained to InSight Crime.

Collapsed Economy and a Crumbling Criminal Empire

Against this backdrop of clan fragmentation, Venezuela was mired in an economic and social crisis that began in earnest in 2014, just a year after the death of Hugo Chávez. It would go on to reshape Zulia’s criminal landscape.

The country’s state-owned oil industry, which had held through years of state mismanagement and expropriations, collapsed. As petroleum production bottomed out, Zulia’s economy ground to a halt, resulting in food shortages, mass unemployment, and the start of the Venezuelan exodus.

“The economic crisis changed things,” Jorge Govea Cabrera, the coordinator for the Venezuelan Violence Observatory (OVV) in Zulia, told InSight Crime. “There was a surge of violence, young people started joining gangs, and the violence mutated from largely interpersonal to largely related to serious organized crime,” he said.

These changes in criminal dynamics would take place while the Meleán mafia was under the leadership of Antonito’s son, Tirso, who took control after Nelson’s death in 2012.

Tirso briefly tried to play the part of a respected businessman embodied by his father, even making a last-ditch effort to defend his reputation in an exclusive 2015 interview with Zulian newspaper, Versión Final, where he denied any connection to extortion or to a string of recent homicides linked to the Meleán.

But soon after, he dropped all pretense of the Meleán as a successful business family.

Instead, together with his cousin, Bernardino, alias “Willy,” Tirso ushered in a more violent and openly criminal era for the family.

He began openly threatening anyone who got in his way, even publicly promising to murder police officers and their families after a security raid destroyed Antonito’s home and killed Tirso’s reported protégé in August 2017. A month later, he ordered a grenade attack that killed one of the police officers involved.

But Tirso also sought to get himself out of the line of fire. His arrest in 2018 did not come in Zulia, or even Venezuela, but in the US state of Texas, where he was detained for being in the country illegally and for illegal possession of a firearm. He would serve three years in a US prison before being extradited to Venezuela, where he remains in prison.

Willy was the next Meleán to take the reins, just as Zulia’s violent, competitive, and chaotic criminal landscape was spiraling downwards.

“2019 was a horrible year,” Ricardo Acosta, a former president of Zulia’s Chamber of Commerce, told InSight Crime. “Violence picked up, and gangs started to use grenades. Because many owners had left their businesses to live elsewhere, extortionists also started killing employees as a way to get to owners, if they refused to pay.”

Willy fled to Colombia, where he tried to set up drug trafficking operations in the country’s urban centers, according to security intelligence reports seen by InSight Crime.

His gamble didn’t pay off. Far from helping the Meleán to escape Zulia’s mafia wars, a new war soon began, pitting the clan against one of its former sicarios, Erick Alberto Parra Mendoza, alias “Yeico Masacre.”

Masacre, a Venezuelan military deserter-turned-extortionist in the Zulia municipality of Cabimas, was first linked with the Meleán around 2017, reportedly as one of Tirso’s hitmen. It appears that he accompanied Willy in his move to Colombia before turning on the Meleán in 2020.

His betrayal would prove catastrophic for his former bosses. Violence between Yeico Masacre and the Meleán dominated Colombian headlines as a series of high-profile tit-for-tat murders terrorized major cities, including Bogotá and Santa Marta.

In November 2020, following an eight-month operation that infiltrated the Meleán’s inner circle, police gunned Willy down in the northeastern Colombian department of Santander.

The Melean family was now truly leaderless.

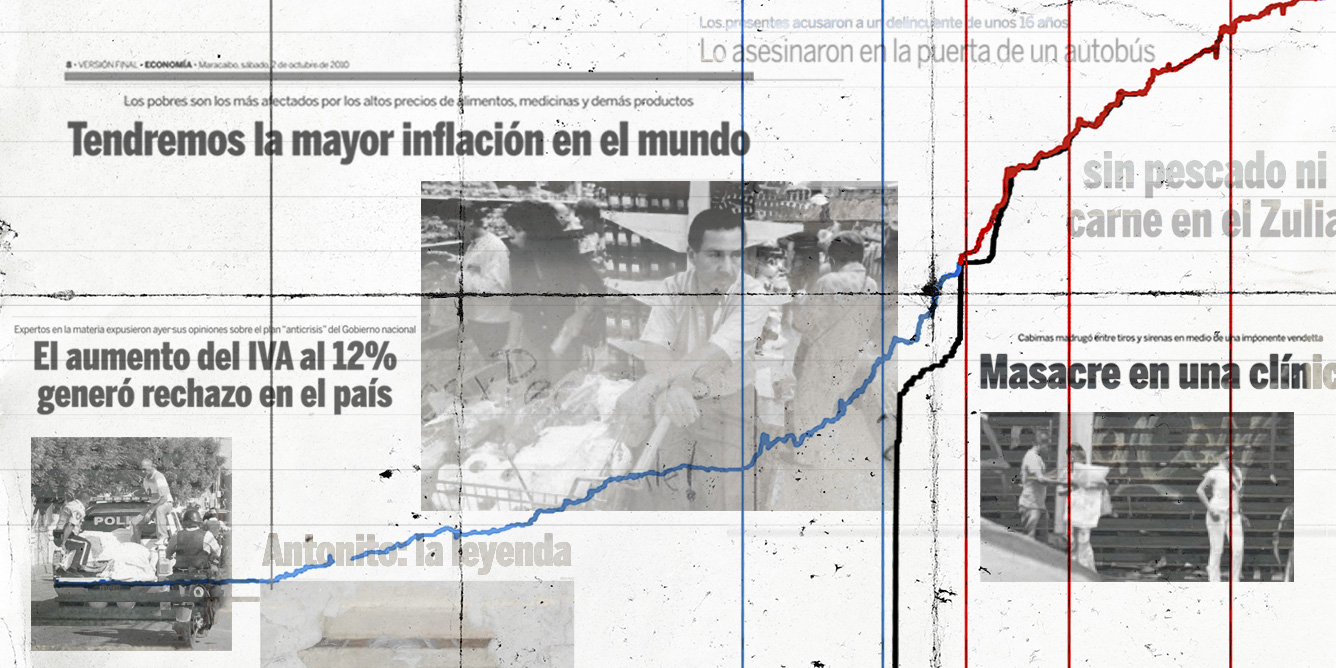

Scroll through Zulia’s headlines — often published side-by-side — to see how the Venezuelan economic crisis and the chaotic spiral of the state’s criminal world unfolded in parallel. Source: Versión Final and El Regional

The Rule of Terror

Today, Zulia has no single criminal leader. Instead, terror, violence, and whichever gang can supply the most of these on any given day dominate the criminal landscape.

With the Melean nearly destroyed, Yeico Masacre’s gang, now calling themselves “Yeico Masacre Armed Group” (Grupo Armado Yeico Masacre – GAYM), reappeared in Zulia. His penchant for flashy violence earned him a spot on Venezuela’s most-wanted list, but it didn’t make him the uncontested new ruler of Zulia’s underworld.

In May 2022, a police intelligence report seen by InSight Crime listed 17 gang leaders as priority targets. Some of these are connected to the fallen Meleán empire, like Adriancito’s gang, which once ensured Meleán criminal interests in Cabimas prison and now runs extortion operations in Cabimas municipality.

Antonito’s old rival, Wilmer Matos, still operates in Miranda municipality, where he competes with Yeico Masacre and another former Meleán sicario, Yet Nava, for control. In the municipality of La Cañada de Urdaneta, three former Meleán hitmen are seeking to replace John Wade who was killed several years earlier.

“Every time a leader dies, four other leaders emerge — that’s why there are so many gangs in Zulia,” an active security official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, told InSight Crime.

The turnover is fast and new players — forged in the breakdown and insecurity of the Venezuelan crisis — are ruthless, uncompromising, and ostentatiously violent. Their criminal operations revolve almost exclusively around extortion.

“Now, they’ll say — give me your car, your engine, your boat — -and if that means you can’t fish anymore, they don’t care,” an extortion victim from La Cañada de Urdaneta told InSight Crime.

As the number of such groups has multiplied, many business owners have found themselves extorted by two, three, or even four gangs at once. These gangs have also expanded their targets to include institutions that were once considered off-limits, such as schools and hospitals.

This no-holds-barred approach has driven whole sectors out of business, worsening Zulia’s downward economic spiral.

The crisis, in turn, has boosted gang recruitment. Many schools have closed, and numerous Venezuelans have fled abroad to earn money to send home, leaving vulnerable children behind.

“The gang members…today are largely young kids — 16-20 years old on average — who are not satisfied with the available economic opportunities. They’re given power, the ability to kill. The violence goes to their heads,” a local official, who asked to remain anonymous for fear of gang retaliation, told InSight Crime.

The sheer number of potential recruits has made them expendable, rendering militaristic security operations ineffective.

Meanwhile, gang leaders risk little. Following in the footsteps of Willy and Tirso Meleán, Yeico Masacre, Adriancito, Conas, and most other Zulia gang leaders have used their criminal profits to move abroad to countries including the United States, Colombia, Ecuador, and Panama. From there, they can direct operations in Zulia with relative impunity since the security forces in these countries lack communication and cooperation agreements with Venezuela.

The Venezuelan government’s response has not been swift or successful.

Large military operations have already proven ineffective, and authorities’ calls on business owners to report extortion threats in the wake of the Carnival weekend attacks also failed to yield long-term results.

“My cousins and I have reported extortion to [Venezuela’s criminal investigation unit], but it’s all in vain,” a business owner in the hyper-violent municipality of La Cañada de Urdaneta told InSight Crime. He added that, despite a large contingent of security forces in town, they do little to stop extortion.

Faced with a dwindling base of legal businesses to extort, a few gangs have shifted their approach.

In La Cañada de Urdaneta, one of the municipalities most affected by extortion, the dominant gang is run by Guillermo Rafael Boscan Bracho, alias “Yiyi,” who is seeking a somewhat more cooperative relationship with his extortion victims.

Business owners there told InSight Crime that Yiyi has started negotiating extortion payments based on what victims can afford, attempting to fight off competing gangs from extorting those “under his protection,” and even working to provide them with some economic benefit in exchange for extortion rent.

So far, however, this “ordered” behavior is minimal and falls far short of the rule-based criminal world once run by Antonito. There is no guarantee that things will improve. Those who can leave are doing so in droves.

“My sister has left, my brother has left, and I’m thinking about it too,” said the businessowner from La Cañada de Urdaneta, who has faced threats and extortion. “We cannot keep going this way.”