The Chilean government has opened up a new front in the fight against drug trafficking, incorporating social and cultural approaches to the country’s insecurity crisis by targeting “narco” mausoleums and funerals.

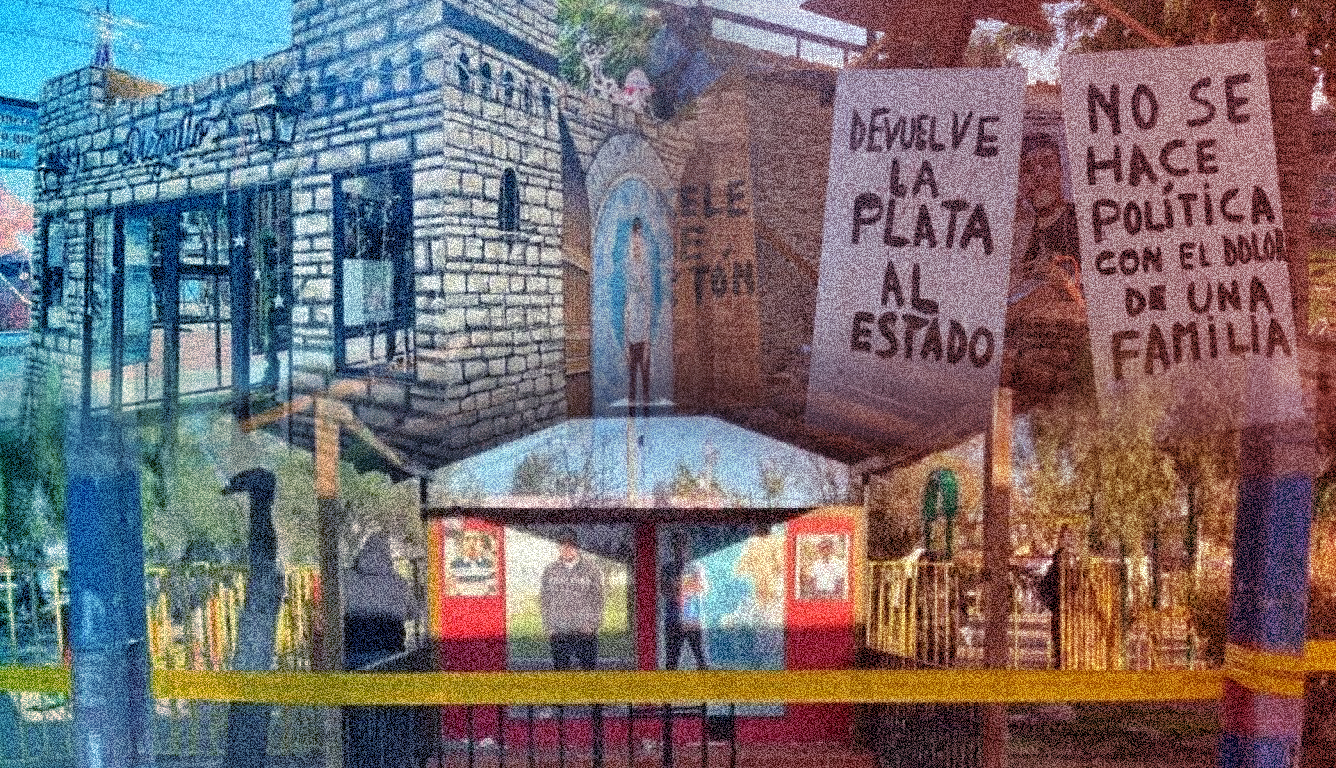

Authorities demolished a narco mausoleum in Buin, a city in the Santiago Metropolitan Region (Región Metropolitana), on September 29. The mausoleum had been erected in honor of a member of a local microtrafficking gang who died by suicide in 2022.

The Buin mausoleum was the tenth such structure demolished in Santiago since June, according to a government press release.

SEE ALSO: Chile Hands New Powers to Police as Security Deteriorates

Narco mausoleums are commonplace in Chile. Authorities have identified at least 30 structures in Santiago and dozens of others around the country. After a criminal gang members’ death, other members and families of the deceased will often erect structures in parks and other public spaces to honor their memories. These mausoleums usually include murals and photos among other objects.

Authorities, however, see the mausoleums as harmful, claiming that they honor violence and perpetuate societal acceptance of criminal activity. They also serve as landmarks for some of Santiago’s gangs, who use the structures as meeting points and to delineate territory, Eduardo Gatica, head of the anti-narcotic wing of Chile’s investigative police force in southern Santiago, told InSight Crime.

The destruction of the mausoleum in Buin followed a September 27 announcement by Chilean President Gabriel Boric of new legislation targeting “narco” or “high-risk” funerals.

The regulations, which the government expects to pass through Congress expeditiously, stipulate that “high risk” funerals must be completed within 24 hours after the death, and have to take place exclusively in the cemetery where the burial will take place. The government has not yet established the process by which funerals’ risk levels will be decided.

Similar to narco mausoleums, narco funerals are a common way criminal groups honor fallen comrades. The practice became popular in Mexico, but in Chile they have transformed into huge and potentially dangerous public spectacles, with armed gang members often firing weapons indiscriminately into the air.

“They affect the safety of the neighbors, who have to coexist with these types of cultural manifestations,” Ainhoa Vásquez, a professor at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México – UNAM) who studies narco culture and literature, told InSight Crime.

InSight Crime Analysis

Chilean authorities are looking to clamp down on what it sees as the glorification of crime by taking back public spaces and increasing social investment.

The Chilean government has emphasized the importance of investing in plazas, parks, and other infrastructure in neighborhoods affected by narco mausoleum demolitions. After previous demolitions in the Santiago area, authorities announced projects to renovate sidewalks, and install exercise equipment and children’s games where the mausoleums once stood.

Despite one instance where a gang mocked Boric for the demolitions, these measures against mausoleums have been popular in the communities they affect, both Vásquez and Gatica told InSight Crime.

SEE ALSO: Northern Chile Struggling to Contain Skyrocketing Homicide Rate

“It seems to be very effective at a symbolic level. It is saying that there are other ways to coexist that are not through drug trafficking,” Vásquez told InSight Crime.

“But, the drug trafficking issue is something at an international level that is very difficult to stop,” she added.

Measures against narco mausoleums and funerals are a direct response by the government to a sharp deterioration in citizen perceptions of security in Chile in recent years. A survey published by market research firm Ipsos in May found that violence is the primary topic worrying Chileans, despite the country’s historically low levels of violence and criminality.

The drop in citizen security has been spurred by the increased transnational drug trafficking, as well as foreign criminal organizations such as Tren de Aragua. Violence has also worsened. Homicides rose 32% from 2021 to 2022.

The increased prevalence of narco mausoleums and funerals is a direct consequence of this increased influence of transnational crime groups, both Vásquez and Gatica said.

“This is an imported phenomenon, it is not Chilean. It has come from Central America over the course of the last 10-15 years,” Gatica told InSight Crime.