White-sand beaches that were once designated for tourists have become camping grounds for thousands of migrants in Necoclí, a small town situated on the Gulf of Urabá’s eastern shore, on Colombia’s Caribbean coast.

At the water’s edge, migrants from Venezuela, Ecuador, China, Haiti, and the Middle East have set up hundreds of tents of different sizes and colors crammed together in uneven rows. Between this Tetris board of temporary shelters, families cook meals with portable stoves, children run in and out of the ocean, and vendors sell everything needed to make a hard trek: hiking boots, SIM cards, empanadas, and more.

The last week of February, the beaches were particularly crowded. On February 23, Colombian authorities arrested two boat captains transporting migrants from Necoclí to Acandí on human trafficking charges, aiming to disrupt access to the Darién Gap, one of the main routes taken by migrants heading north.

With no guarantees that the authorities would leave other captains alone, boat companies suspended transport services across the gulf, leading to a buildup of stranded migrants that reached 3,000 at its peak.

SEE ALSO: Gaitanistas License Migrant Smuggling in Colombian Darién Gap: Report

Under the scorching sun, migrants grew impatient. Most were eager to set out on the hazardous multi-day trip across the Darién Gap, the slice of treacherous jungle terrain that divides Colombia from Panama. But until maritime traffic resumed, they were confined to Necoclí’s makeshift migrant shantytown. There, humanitarian workers in blue and red vests patrolled the area, offering health services, water purifying pills, and legal advice to the few migrants who may stay in Colombia.

Normally, around 1,000 migrants board ferries from Necoclí or the neighboring beach town of Turbo each day. The boats transport them to Acandí, a municipality across the gulf, which sits on the border with Panama. There, the jungle trek begins.

From the shadows, members of the Gaitanista Self-Defense Armed Forces of Colombia (Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia – AGC), also known as the Gulf Clan (Clan del Golfo) or the Urabeños, the region’s most powerful criminal group, monitor the situation closely.

The AGC has monopolized the entire migrant ecosystem: they define what routes migrants can take and charge a tax for migrants who want to transit through their territory. Though multiple routes through the jungle exist, the AGC permits travel only through Acandí, which benefits the group in many ways.

Migration ‘Crisis’ Turns a Profit for the AGC

The Darién has been a path for migrants heading to the United States since the 1990s. But the recent migration surge began shortly after the assassination of Haitian President Jovenel Moïse in July 2021, which prompted groups of Haitians to gather in Urabá to travel northward.

At first, hundreds arrived, helping solidify the underpinnings of the migration economy. Migrants from Colombia’s neighbors Ecuador and Venezuela added to the waves of Haitians. But as Central American countries tightened visa restrictions to curb migration through their territories, groups of up to 1,000 migrants from Latin America, Africa, and even Asia, began arriving in the Gulf of Urabá each day.

The Gulf of Urabá region is the stronghold of the AGC, which emerged from the ashes of the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia – AUC), one of the country’s paramilitary armies that demobilized in 2006.

Many migrants who come to the Gulf of Urabá are unaware they are entering AGC territory. Aside from the occasional “AGC” graffiti on buildings and a few men patrolling on motorcycles, the group’s presence is relatively inconspicuous.

But the AGC has uncontested control of the region and reaps the economic benefits of the booming migrant economy.

From Necoclí and Turbo, the trip across the Darién can cost between $350 and $500, including the ferry to Acandí and jungle guides. Migrants seeking quicker and safer passage can pay up to $1,000 to access the Capurganá route, which passes through the northern part of Acandí.

“It can be a day or less or a little more, depending also on the pace. It’s a route widely used by Chinese, Afghans, and Indians,” a humanitarian worker from Necoclí told InSight Crime.

The profits collected solely from transport packages sold to migrants last year could have been between $17.5 million and $25 million, with nearly half a million migrants crossing the Darién in 2023.

The AGC also taxes every business taking part in the migrant economy in the Gulf of Urabá approximately 10% of its profits, local sources told InSight Crime. This includes formal businesses like hotels, restaurants, and boat companies, as well as informal businesses like street vendors. The group uses its total control of the region’s migrant economy to concentrate migrants and service providers at specific points, thereby making collection easier.

AGC Creates Migration Bottleneck in Acandí

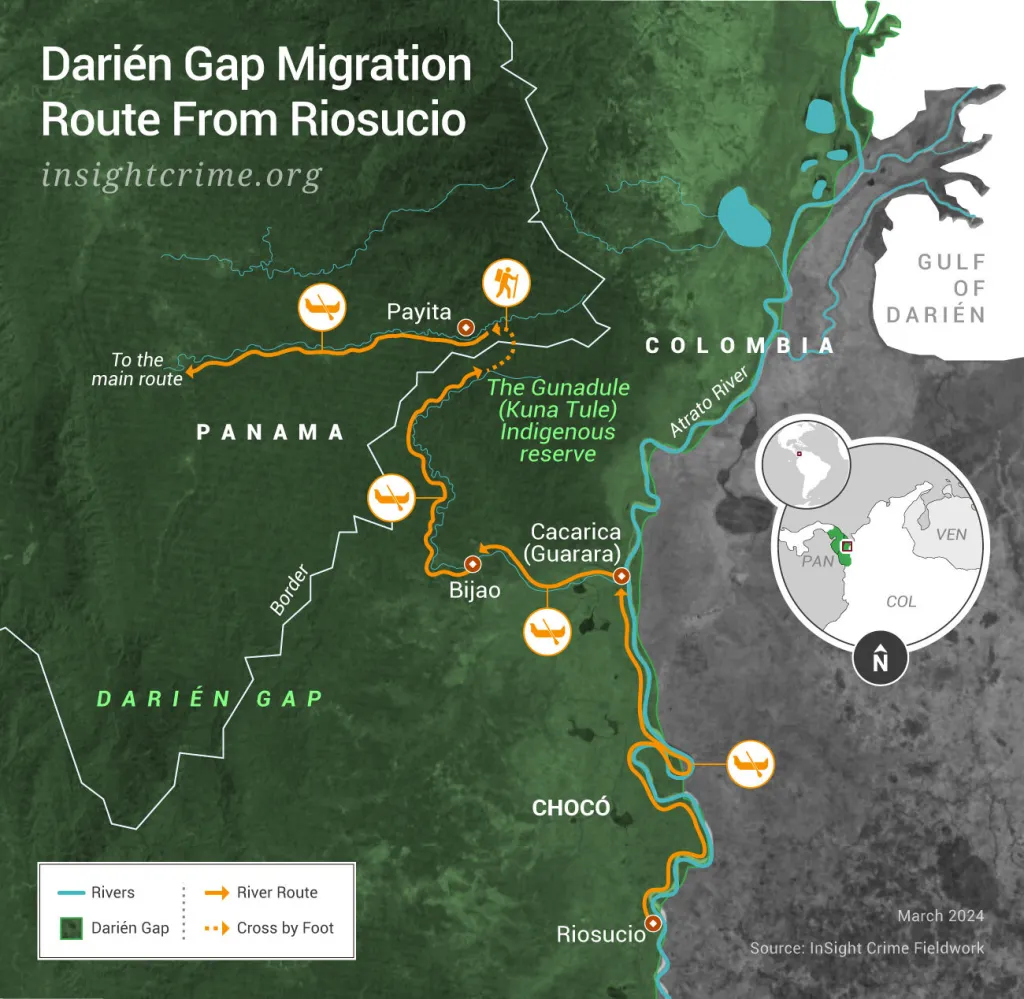

The AGC has created a choke point in Acandí to maximize its revenues by ensuring that no business operates without paying fees to the group. But Acandí is not the sole municipality with routes through the Darién. Riosucio and Unguía, located directly south of Acandí, are the starting points for alternative routes to Panama.

Riosucio, for instance, is arguably the most accessible municipality in northern Chocó for migrants, as it can be reached by road from the Colombian department of Antioquia. Brazilians, Cubans, and Haitians searching for routes through the Darién began arriving in the municipality on a small scale starting in 2019, according to a Riosucio resident who often provides shelter for migrants, but spoke on the condition of anonymity due to security concerns.

SEE ALSO: How Organized Crime Profits from Migrant Flow Across Colombia’s Darién Gap

The route from Riosucio entails traveling north to the village of Cacarica before heading northwest on rivers to the border with Panama.

“You enter the Pan-American Highway. You don’t have to cross as many mountains. The road is much flatter, the path is straighter,” said a member of an international organization in Necoclí, who assists migrants before they start the Darién Gap trek, but wished to remain anonymous for safety reasons. But the AGC doesn’t allow it: “It is used by the group for other types of activities,” they added.

“The other day some Brazilians came, and they went [up the river toward Cacarica], and the paramilitaries [the AGC] caught them,” said the Riosucio resident. “The paramilitaries made them harvest coca leaves and gave them food, but they didn’t let them continue. They were turned back.”

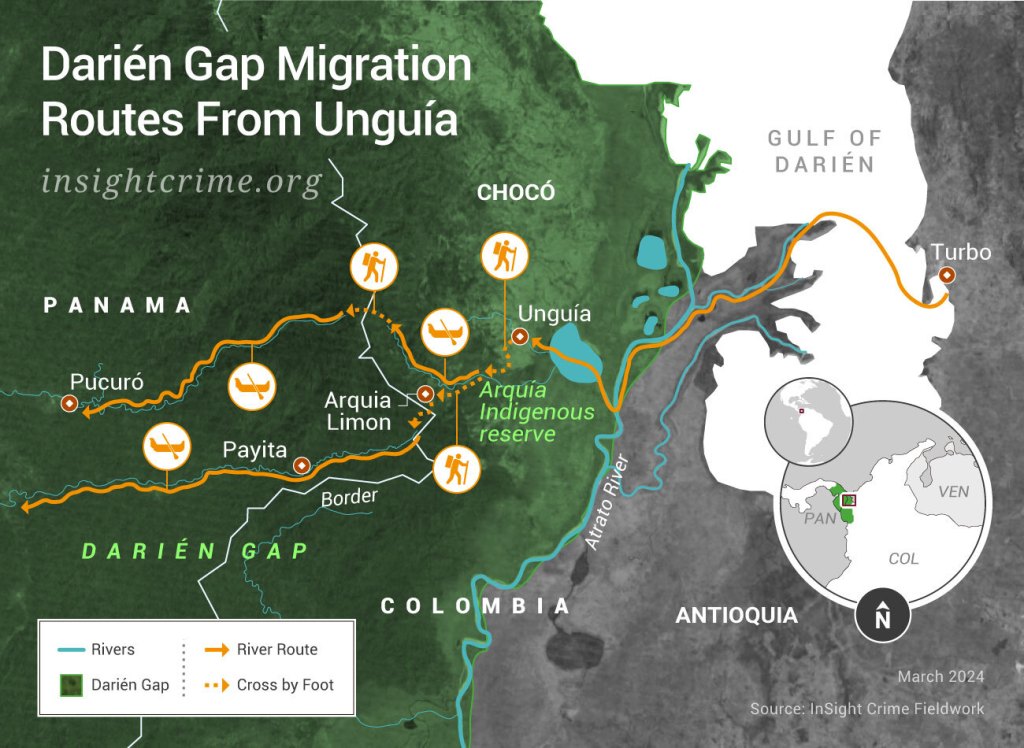

Another two routes leave Unguía and cross through the Guna Dule Indigenous reserve, which spans Colombia and Panama. Indigenous communities have used these ancestral routes for hundreds of years. They are better defined than other paths, and the trek takes just a day and a half in good weather conditions, compared to three to five days from Acandí.

“This route through Unguía is less risky for migrants, as there are not as many big cats or wild beasts,” an Unguía public official, who wished to remain anonymous for security reasons, told InSight Crime.

Since November 2022, there have been only two known attempts to move migrants along these routes, according to a report from Colombia’s and Panama’s Ombudsman Offices. In both cases, the Panamanian National Border Service (Servicio Nacional de Fronteras – SENAFRONT) stopped the migrants and their guides once they left the Indigenous reservation on the Panamanian side, and forced them to return to Colombia.

Alternate Economies

Along the roads on the outskirts of Riosucio is a massive outdoor warehouse of felled timber. Entire logs sit beside cut planks of wood, ready to be used in construction. Tractor trailers wait to load their cargo. There are no migrant encampments or even traces of people transiting through — a stark contrast to the overcrowded beaches of Necoclí.

As visitors arrive, motorcycle taxis dart around, calling out to the few who have made the four-hour trek from Apartadó, the biggest city in Urabá, along mostly unpaved roads. A pervasive sense of surveillance hangs over the town.

Other motorcyclists pull up beside their colleagues, asking the drivers where their passengers are headed and sending quick-fire audio messages via WhatsApp about their destinations before speeding off. Children, men, and women sit on porch stoops watching those passing by, some of whom discreetly send messages. It seems like every movement outsiders make is tracked, from their accommodations to their interactions. Holding the reins of this tight control is the true authority in the town: the AGC.

While migration has become a highly profitable revenue stream for the AGC in Acandí, the group tracks visitors and deters migration from other towns to maintain their territorial control in these municipalities, which allows them to participate in criminal economies, including drug trafficking and illegal logging.

For decades, the Gulf of Urabá has been an important dispatch point for cocaine smuggled all over the world in banana crates, a trade that has made the AGC and its leadership immensely rich. Although migration is an increasingly important revenue stream for the group, drug trafficking continues on a massive scale.

With international organizations and government presence focused on migration in Acandí, the AGC has much more freedom to carry out drug trafficking through Unguía and Riosucio. If migrants transited these municipalities as well, the presence of authorities in the area would likely increase.

While the AGC principally moves cocaine through ports along Colombia’s Atlantic coast via boats loaded with tons of the drug, land routes through the Darién, which begin in Acandí, Unguia, Riosucio, and Jurado, are still used for smaller quantities of cocaine.

The AGC initially began organizing the routes so that the migration trail would not cross with those used for illicit substances. There have even been reports of anti-personnel mines bordering the main route in Acandí, to dissuade migrants from using them, according to social leaders and municipal officials in northern Chocó.

Beyond trafficking routes, the AGC has also established considerable control over coca cultivation. With the price of coca collapsing in southern Colombia, the AGC has also begun recruiting coca farmers from areas like Putumayo and Cauca, where coca cultivation is well-established, to set up plantations along small rivers in Riosucio, according to a town resident. InSight Crime was unable to verify this with other sources.

“The river has villages that never existed before and have been created by those who have arrived,” the resident said. “They have five or six workers, seven little houses, and they start building, they bring in some air conditioning and a small refrigerator. During the day they are working, and at night, drinking cold beer.”

The most recent data measured 1,055 hectares of coca cultivation in Riosucio in 2022, accounting for one-fifth of Choco’s total coca cultivation and making it the second-most densely cultivated municipality in the department.

“[The AGC’s] main income would have to be coca, coca base,” said a Riosucio social leader. “They tax cattle farming, and it contributes [to their revenue], but very little. Rice, very little, and bananas, very little as well.”

The group also profits significantly from illegal logging in Riosucio and Unguía. While logging is an ancestral and self-sustaining practice in Riosucio, unauthorized logging mafias exploit the dense forests, searching for fine woods available in the humid jungle environments.

This wood is often brought back to Riosucio and transported to major cities for sale. The AGC charges a tax from the truckers who buy and move the timber, another important revenue source for the group, according to a social leader in Riosucio involved in the local timber trade.

More migration across these territories would make it more difficult for the AGC to keep its monopoly on these illegal economies, as migration often brings with it a greater institutional presence in the form of humanitarian organizations and law-enforcement authorities. However, if the government concentrates its efforts on sealing the crossing through Acandí, the AGC has such a firm hold on Unguía and Riosucio that it might suddenly open the entrance to migrants as a plan B.

According to the public official in Unguía, “They could reactivate the route again at any moment.”

Featured image: Migrants camp on the beaches in Necoclí, Antioquia. Credit: Henry Shuldiner