Listen to this article

Insecurity is rising in Paraguay, and the government is increasing recruitment opportunities for organized crime groups by jailing thousands of people merely accused of crimes alongside actual convicts.

Many Latin American countries employ the practice known as pretrial detention, putting suspects behind bars before they have had a trial. But Paraguay surpasses all its South American neighbors, with two-thirds of prisoners yet to be sentenced, according to data from the Institute for Crime & Justice Policy Research at the University of London.

Paraguay has ramped up its use of pretrial detention over the past two decades in response to concerns about crime, but the policy appears to have missed the mark. Crime is on the rise and citizens are demanding a response.

SEE ALSO: Prosecutors, Mayors and Prison Directors – Paraguay’s Frightening Assassination Problem

From the first to the second half of last year, theft and robberies increased by 6%, according to data from the National Police. This rise has continued through the first quarter of 2023: a Public Ministry report shows cases of theft and robbery increased 10% between January and March of this year, leaping from 6,665 to 7,351.

In the criminal hotbed of Alto Paraná, a wave of violence led to the appointment of a new police commissioner last week.

Paraguay’s reliance on pretrial detention has not only failed to contain crime, it may be fueling rising insecurity. The practice puts non-convicts in proximity with long-time criminals, making them ripe for recruitment. This is especially true in Paraguay’s heavily overcrowded prisons, where authorities cede much control to the prisoners.

The Rise of Preventative Imprisonment

Paraguay’s high ratio of pretrial detainees is the result of its preventative imprisonment policy, where judges incarcerate anyone suspected of a crime.

“Before, in Paraguay, there was an assessment of what measures would have to be taken before you were sentenced, depending on the crime you were being accused of,” Carlos Peris, a sociologist at the National University of Asunción, told InSight Crime. Now, he said, they just send them to jail.

The country’s crime policy changed in the late 90s and early 2000s, according to Jorge Rolón Luna, a lawyer and researcher at the Catholic University of Asunción. Violence was on the rise, with Paraguay’s homicide rate peaking in 2002, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

In an interview with InSight Crime, Rolón Luna summarized the current attitude toward crime in Paraguay: “Someone’s accused of a crime? They have to go to jail. Later you can figure out if they committed a crime or not.”

This policy led to a steady rise in Paraguay’s incarcerated population. In 2000, 60 Paraguayans per 100,000 were in jail; by 2020, that number had grown to 194, according to the Institute for Crime & Justice Policy Research.

Prison overpopulation is driven by the overuse of pretrial detention and the justice system’s slow processing of detainees’ cases, according to Rolón Luna.

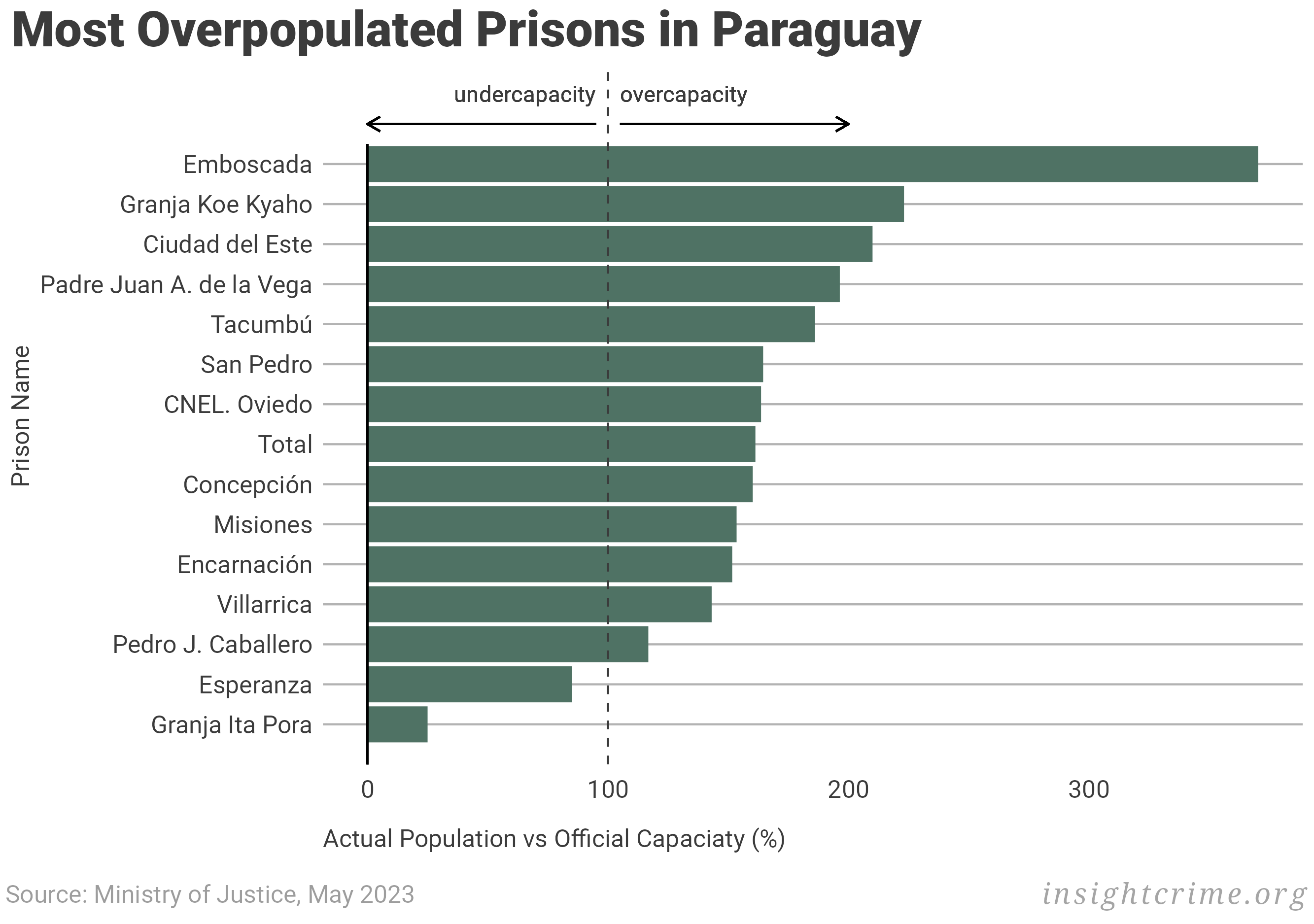

As a result of the backlog in the legal system and the overuse of pretrial detention, 16,105 people are in jail in Paraguay; the official capacity of all the country’s jails is 9,985.

In most Paraguayan prisons, the number of people awaiting trial alone exceeds the facility’s official capacity.

Organized Crime Thrives in Overpopulated Jails

As prison populations have swelled, conditions in the facilities have worsened. Guards are often outnumbered, leaving them incapable of stemming violence or protecting inmates.

“These dynamics mean that unsentenced prisoners try to find a way to survive because the living conditions are very complicated,” said Carlos Peris. “A good way to survive from day to day is to join one of these [criminal] groups.”

Gangs have gained control inside many of Paraguay’s detention centers, with cases of inmates openly cooking drugs, assassinating a former prison director, and engaging in brutal violence.

Often, people awaiting trial cannot be separated from members of organized crime groups or other dangerous prisoners. This means that someone suspected of picking someone’s pocket could be sharing space with members of organized crime groups or other dangerous prisoners.

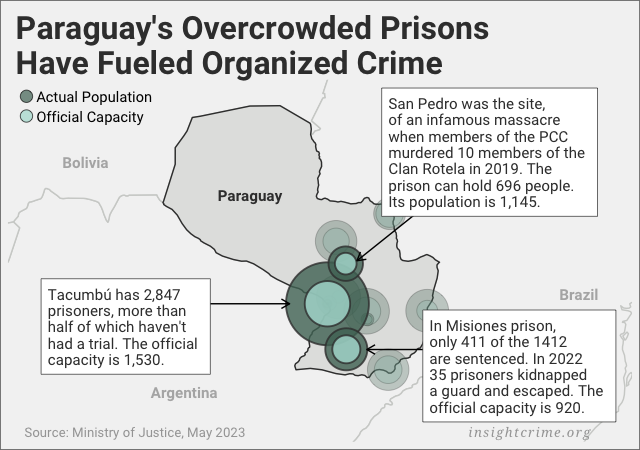

Indeed, organized crime groups in Paraguay have long used recruitment opportunities provided by overcrowded prisons to expand their ranks. Though it began operating in Paraguay’s prisons early on, the Clan Rotela began focusing on recruiting within prison walls after its leader, Armando Javier Rotela, was sent to Nacional de Tacumbú prison in 2016. Even with Rotela in jail, the group has continued its microtrafficking empire.

SEE ALSO: Is Brazil’s PCC Trying to Take Over Paraguay’s Marijuana Business?

Perhaps the largest organized crime group in Paraguay today, is the First Capital Command (Primeiro Comando da Capital – PCC). This gang started out as a self-protection group after a 1992 massacre in Brazil’s Carandiru prison in São Paulo. During its rise, the PCC capitalized on the insecurity of overpopulated prisons to recruit new members, growing from just eight prisoners to 10,000. The group spread to Paraguay, where it controls many of the trafficking routes from Paraguay to Brazil. Hundreds of PCC members have been arrested in Paraguay, and while some have been deported back to Brazil, others remain in Paraguayan jails, leading to violent clashes with Clan Rotela members.

A Regional Issue

Although Paraguay has the highest pretrial detention rate in South America, it’s not the only country where organized crime has capitalized on prison overcrowding caused by this policy.

The country with the second-highest pretrial detention rate is Bolivia, with 66% of its incarcerated population without a sentence, according to the Institute for Crime & Justice Policy Research. Bolivia’s reliance on pretrial detention has caused the number of inmates to soar to 264% of the capacity of its prisons, and organized crime has taken root within its facilities. In its largest prison, Palmasola, inmates took control and started dealing weapons and drugs. The prison has since witnessed deadly riots and prisoners have used homemade flamethrowers in battles for control.

With 62.5% of its prisoners awaiting trial, Venezuela’s pretrial detention rate is the next highest. There, the most powerful homegrown organized crime group is Tren de Aragua. Like the PCC, Tren de Aragua was formed inside a prison and has since expanded to other countries. Though focused on extortion, Tren de Aragua has a diverse criminal portfolio. It took advantage of the Venezuelan refugee crises to become a major player in migrant smuggling and has committed kidnappings in Venezuela, Colombia, Peru, and Chile. Despite being an international criminal group, Tren de Aragua is still run from inside prison walls.