Coca cultivation in Peru reached an all-time high in 2022, with the largest growth in crops occurring outside of traditional cultivation zones, according to a new report by the Peruvian government.

Peru, the world’s second-largest coca cultivator behind Colombia, had 95,008 hectares of land dedicated to coca cultivation last year, the report estimates. The historic figure represents an 18% increase from the 80,681 hectares recorded in 2021 and a nearly 54% increase from the 61,777 recorded in 2020.

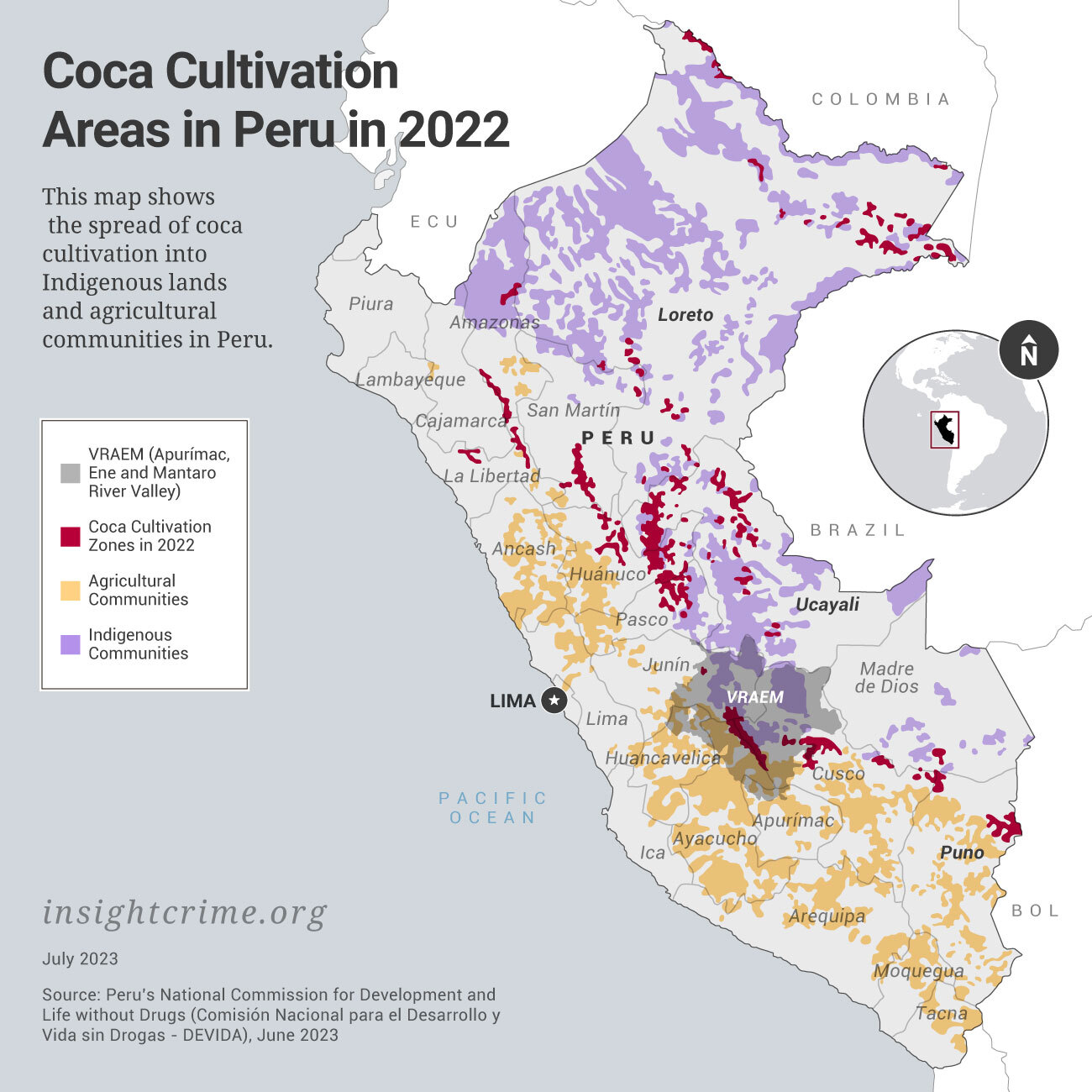

The study published June 26 by Peru’s National Commission for Development and Life without Drugs (Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo y Vida sin Drogas – DEVIDA) used satellite imagery to monitor the development of coca plantations around the country.

Coca leaves are the base material used in cocaine production, which has reached all-time highs in Latin America. While the United States and Europe remain the biggest consumers of the drug, the boom has also resulted in the development of new markets in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia.

Here, InSight Crime explores the report’s findings about the quantity and geographic distribution of the country’s coca crops.

Coca Expands in Indigenous Communities, Protected Areas

The expansion of coca cultivation into Peru’s Indigenous territories and protected areas is driving the crop’s growth.

Coca cultivation in Indigenous territories increased 87% in 2022, rising to 18,674 hectares from 9,989 in 2021. Coca grown in Indigenous territories now represents 20% of the country’s total cultivation area.

Indigenous communities are largely not responsible for the expanding cultivation, according to Pedro Yaranga, a Peruvian security analyst. Rather, people dedicated to coca cultivation have entered Indigenous areas, which are attractive for their remoteness.

“They invade those lands or they temporarily rent the lands they are entering,” he told InSight Crime.

The encroachment of coca cultivation — and the drug trafficking that accompanies it — has sparked resistance from Indigenous communities. Traffickers have responded with intimidation and violence, killing at least four community leaders between 2019 and 2022 in the Amazon region.

SEE ALSO: Drug Traffickers in Fresh Round of Violence Against Peru’s Indigenous Communities

Coca cultivation in protected areas has also expanded from 328 hectares in 2021 to 439 in 2022. In buffer zones designed to safeguard protected areas, hectarage increased from 12,436 to 14,426 during the same period.

DEVIDA chief Carlos Figueroa said coca’s expansion into protected areas is particularly worrying.

“Beyond the damage that coca bush cultivation has always caused in national territories, now the damage is even more powerful because it also includes environmental crimes in … protected natural areas [and] buffer zones,” he told reporters.

Production Continues to Shift to Peru’s Peripheries

Coca cultivation in Peru’s border departments has continued to grow in 2022, the report shows.

Border departments are attractive for multiple reasons.

Many areas in these departments are very remote, making detection and interdiction by authorities difficult. Moving production closer to the borders is also more cost-efficient, allowing easier to access to Brazil and Bolivia, through which cocaine travels to consumer markets.

The presence of criminal organizations that skirt Peru’s borders has also facilitated cultivation in these areas, with groups such as Colombia’s ex-FARC mafia and Brazil’s First Capital Command (Primeiro Comando do Capital – PCC), controlling cocaine flowing out of Peru.

SEE ALSO: Ucayali, Peru’s Drug Trafficking Gateway to Bolivia and Brazil

Coca cultivation in Peru’s border departments accounted for 45% of national hectarage in 2022, up from 27% in 2019. The increase has been driven by exploding cultivation in the border departments of Loreto (173% growth from 2018 to 2022), Ucayali (467%), and Puno (57%).

Meanwhile, coca’s expansion in the Valley of the Apurímac, Ene, and Mantaro Rivers (Valle de los Ríos Apurímac, Ene y Mantaro – VRAEM), Peru’s traditional coca cultivation hotspot, has slowed. The region accounted for 47.6% of the country’s hectarage in 2019, but only 37.6% in 2022.*

While the report recorded sharp increases in coca cultivation in border departments in the last few years, Peruvian journalist Ivan Brehaut cast doubt on whether this phenomenon is new.

The government has made progress documenting the extent of the problem, he told InSight Crime, but in years past, authorities “were failing at calculating and detecting the coca crops in Peru, especially in Ucayali.”

Uneven Eradication Efforts

The Peruvian government focused eradication efforts outside of traditional cultivation zones in 2022, the report showed.

The government eradicated 36% of its total hectares in Ucayali in 2022, with the number growing to 62% so far in 2023. The department, however, only accounts for 15% of the country’s estimated coca hectarage.

The same was true for the central department of Huánuco, which holds 4% of Peru’s coca crops but recorded 26% of total eradicated hectares in 2022.

Compared to traditional coca-growing hotspots like the VRAEM, departments like Ucayali and Huánuco are easy targets for the government, Brehaut told InSight Crime. The entrenchment of coca and history surrounding cultivation in the VRAEM make eradication efforts politically and economically risky.

The presence of the Shining Path has also historically posed challenges to the government’s efforts to eradicate coca in the VRAEM. While the group is not as powerful as in the 1990s, a string of attacks on Peruvian security forces in early 2023 confirmed that they are still present in the region, which could further complicate government efforts.

*An earlier version of this article misstated the expansion of coca cultivation in the VRAEM. Cultivation has expanded in the region, but at a slower rate than the country as a whole. This article was updated on August 7.