The story of Dalila Johana Flores Flores is one of thousands of arbitrary detentions that have taken place in El Salvador. Her experience demonstrates that, under the state of emergency, any person can be labeled a “terrorist” and imprisoned for months, even when there are public officials who assure that she has no relation whatsoever with gangs.

Johana became a “terrorist” on the morning of January 17, 2023. Until that day, she was a 24-year-old woman with no police record, and a mother of a three-year-old girl. She earned her living grinding corn in a nixtamal mill and preparing the dough for the tortillas eaten by almost everyone in the El Maneadero district of Zacatecoluca, La Paz.

Around nine o’clock that morning, a group of about 10 soldiers, led by a female sergeant, showed up at the Flores family home. Johana was grinding corn, as she did almost daily at that time.

The soldiers approached her politely and asked for her ID. The same simple and routine request for identification has become the beginning of thousands of dramas since the Legislative Assembly, at the request of President Nayib Bukele, declared a state of emergency on March 27, 2022.

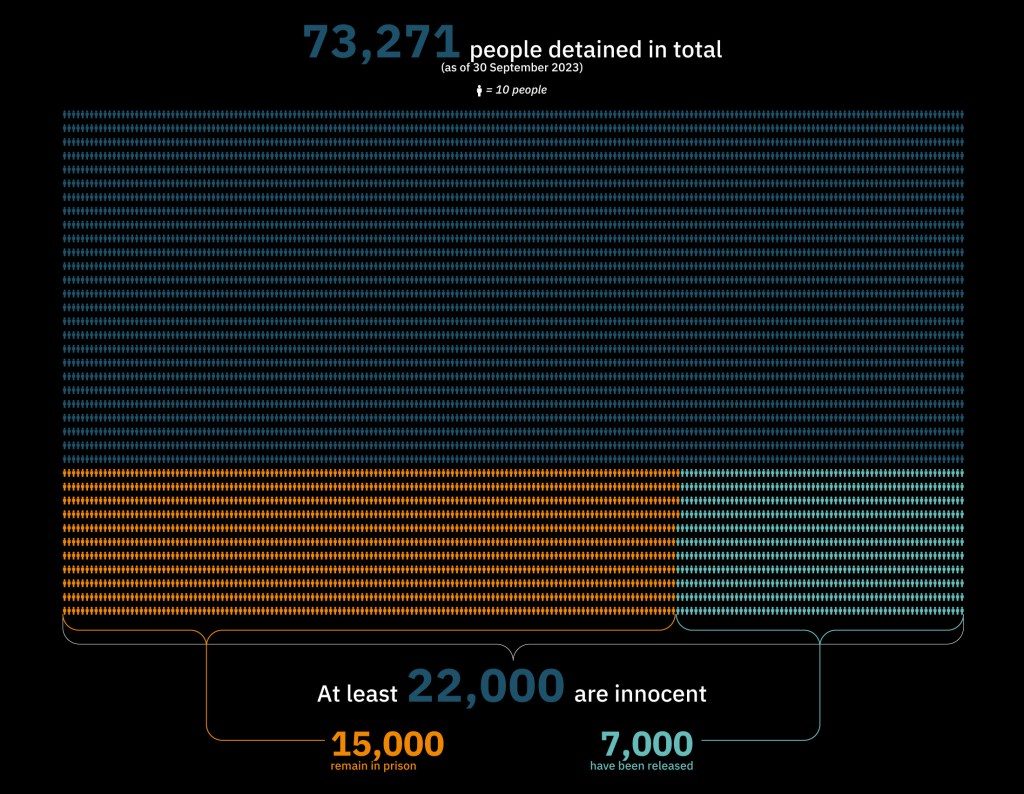

The decree was aimed at the gang members of the Mara Salvatrucha (MS13) and Barrio 18. Salvadoran law classifies these criminal groups as terrorists, and they have tormented families like Johana’s for years. However, under the decree, more than 73,000 people have been detained, many of them due to anonymous calls, or quotas demanded from police and soldiers rather than as a result of serious investigations.

‘Just to Verify’

All detentions begin with that simple, routine ID request. When the soldiers started to inquire about Johana that morning, her father, Francisco Antonio Flores Murillo, returned home. He had just come from caging some cows he owned.

“I was surprised and asked her, ‘What’s going on?’ ‘They asked me for my ID,’ she said. ‘And why?’ I said. ‘To check,’ she replied,” Francisco recalls.

Johana continued grinding corn and attending to the neighbors who came for their corita (25 cents) of masa. Meanwhile, a small group of soldiers walked with the ID to a house a block and a half away. Johana’s family said the house was home to relatives of one of the leaders of the Barrio 18 Revolucionarios in Zacatecoluca, one of the three most important gangs in El Salvador and one of the regime’s main targets.

According to Johana’s relatives, her problem began in that house. They had had serious clashes with this family, and Francisco had organized the community to confront them. Francisco is convinced that the false information that turned his daughter into a “terrorist” was provided by the mother of one of the leaders of the Barrio 18 Revolucionarios in Zacatecoluca, who has been imprisoned since 2018. Francisco believes she accused her daughter out of revenge.

SEE ALSO: El Salvador Police Reports Contradict Bukele’s Triumphalism

“This canton has had a strong presence of gang members, and we organized ourselves. We tried to protect each other, because we are seven brothers,” Francisco said.

“I think they went to show them my daughter’s ID, because a day before, the soldiers had been in that house, and there they misinformed about my daughter and more people, because it was them who formed the gang that operates here,” said Maribel Flores, Johana’s mother.

The irony continues to haunt her.

“The relatives of the real gang members accused my daughter of being a gang member,” she said.

After a while, the sergeant said they would take her to the National Civil Police (Policia Nacional Civil – PNC) station in Zacatecoluca, “just to verify.”

Francisco tried to stop her. He asked them for arrest warrants that they did not have. He gave them Johana’s phone so they could check it, and they returned it because they did not find anything suspicious. They have it at home. The exchange of words was tense but cordial.

“Look,” Francisco told the sergeant, “As far as I know, that’s a lie … That’s how the soldiers are, deceitfully taking people from this and other surrounding cantons, and when they arrive at the police station, they don’t let them leave. My daughter, I’m telling you, has no links with gangs.”

But the decision was made. The platoon waited for Johana to finish grinding, for her to bathe, and then they took her away in a white pickup truck assigned to the armed forces. They kept it at the military post next to the Zacatecoluca Security Prison — known as “Zacatraz” in reference to the infamous prison in San Francisco, California — which is a little more than six kilometers from El Maneadero.

Francisco took his granddaughter in his arms and asked to go with them. Maribel, who had gone to Zacatecoluca to run some errands, went to the police station, but everything went too fast. Maribel said within 15 or 20 minutes, a policewoman laconically informed them that she was being detained “for illicit association,” the designation under which most have been imprisoned since the regime began.

There were complaints and some yelling, but they were not even allowed to say goodbye. The police even threatened to arrest them too.

That same afternoon, Johana was sent to the Apanteos Penal Center in Santa Ana, a department on the border with Guatemala. She spent the night in her new condition of “terrorist.”

Johana’s Defenders

Since the day of the arrest, Johana’s family has gone to great lengths to publicize her case. The exculpatory documents that support this report were presented at the initial hearing or in subsequent judicial proceedings. They have hired a lawyer; they recounted their misfortune to a journalist from El Diario de Hoy; they have spoken to human rights organizations; they have gone to the Human Rights Ombudsman’s Office; they have attended marches and have even written a letter to Bukele, which they sent to the presidential palace.

A veteran agent of the PNC’s Specialized Reaction Force (Fuerza Especializada de Reacción), an anti-gang unit created in 2016, swore before a notary that he investigated the presence of gangs in the El Maneadero canton where Johana and her family live for three years, and concluded that the family members are “honest and hardworking people, respectful of all kinds of authority.”

The police agent even corroborated Francisco and Maribel’s story that the family “was the victim of threats and extortion” by the Barrio 18 Revolucionarios, and that the family home was shot at because the gang members suspected Maribel of being a PNC informant.

In addition to the affidavit of the agent of the Special Reaction Force, they also obtained multiple testimonies from officials and community members confirming that she has no relationship whatsoever with gangs.

The local head of the Catholic Charismatic Renewal movement, Juan Carlos Barahona, also signed and sealed a document that defines Johana as “a very dedicated person and servant of our Catholic congregation” and that she was part of the choir throughout her adolescence.

And even a mayor of Nuevas Ideas, Bukele’s party, defended Johana’s innocence in a letter on his letterhead.

“I have known of her since she was a child, and she has always been dedicated to home and study,” said Nicolas Antonio Garcia Alfaro, mayor of Tecoluca.

But Johana is still detained. She has been locked up in Apanteos for more than nine months.

No one from the family, not even the lawyer, has spoken to her since she was taken away. The last they heard was that she was being held in Sector 3 of the prison in San Juan, a particularly harsh area with minimal access to water, according to her relatives.

Thousands of Innocent People Imprisoned

According to estimates by Socorro Jurídico Humanitario (SJH), an organization that provides legal, psychological, and medical support to regime victims, Johana is just one of 15,000 innocent people still locked up.

“And every day we continue to receive 10 to 15 new cases of people whose relatives had not sought support because they still had, let’s say, the idea of leaving things to the will of God, or who trusted a little in the system,” said SJH director Ingrid Escobar.

SEE ALSO: How El Salvador’s Police Creates, Uses Its Gang Database

“We alone have registered some 1,500 cases of innocents, with names and surnames, of which only 33 have been released,” Escobar added.

In addition to SJH, other entities that keep records are Cristosal, the Human Rights Institute of the University of Central America (Instituto de Derechos Humanos de la Universidad Centroamericana – Idhuca), Tutela Legal Dr. María Julía Hernández, the Center for Exchange and Solidarity (Centro de Intercambio y Solidaridad – CIS) and the Movement of Victims of the Regime (Movimiento de Víctimas del Régimen – MOVIR).

“We believe that all the detainees who have still not been convicted after up to a year and a half of investigation are innocent.” said Samuel Ramirez, representative of MOVIR.

“At least 30% of the people detained during the emergency regime are innocent,” he added.

Thirty percent of the 73,271 that the PNC claims to have captured as of September 30, 2023, equals more than 22,000 people.

Security Minister Gustavo Villatoro said on August 22 in a television interview that by that date, there were “a little more than 7,000 who have been released from these more than 72,000” detainees.

“The justice system is working,” the minister said in the same interview.

The government’s muscular propaganda apparatus continues to highlight the advances in the fight against gangs in an excessively triumphalist tone. But at the same time, the government makes arbitrary detentions invisible. The official discourse has not subtracted the 7,000 innocent people freed up to August from the total number of arrests, and the Bukele administration continues to speak of more than 73,000 “terrorists” detained.

Family Also Persecuted

On October 2, Johana’s family — Francisco, Maribel, and two sisters — took the package of food and personal hygiene products to the Apanteos prison. The canton of El Maneadero is so far away that they had to rent a pickup truck and leave early in the morning to return at night.

Visting the prison is one of the many expenses the family has had to assume since Johana’s arrest. They have also had to pay for her lawyer, trips to deal with paperwork, deposits to her prison commissary account (which they do religiously even though they don’t know if the money makes it to their daughter), and many other expenses.

“It is costing us $525 a month, it’s as if the government is stealing that money from me,” said Maribel with contained rage.

The expenses are assumed by two of Johana’s brothers and the father of her daughter, who migrated to the United States and send remittances. Without this support, they could not meet the expenses of the arbitrary detention.

Meanwhile, Johana’s daughter, who has not seen her mother since the morning of January 17, turned four years old in September. Francisco and Maribel have six children and five grandchildren. A five-foot poster of the recently canonized saint, Monsignor Óscar Arnulfo Romero, presides over the house’s main room.

“If it is already very difficult for the parents from the psychological point of view, you can’t imagine how complex it is to work with the children,” said German Cerros, an Idhuca psychologist.

The day the family traveled to the penitentiary center to deliver the package, they were unable to see Johana, much less talk to her.

“We are hopeful that she is still alive,” said Francisco.