Welcome to InSight Crime’s Criminal GameChangers 2018, where we highlight the most important trends in organized crime in the Americas over the course of the year. From a rise in illicit drug availability and resurgence of monolithic criminal groups to the weakening of anti-corruption efforts and a swell in militarized responses to crime, 2018 was a year in which political issues were still often framed as left or right, but the only ideology that mattered was organized crime.

Some of the worst news came from Colombia, where coca and cocaine production reached record highs amidst another year of bad news regarding the historic peace agreement with the region’s oldest political insurgency, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia – FARC). The demobilization of ex-FARC members has been plagued by government ineptitude, corruption, human rights violations, and accusations of top guerrilla leaders’ involvement in the drug trade. And it may have contributed directly and indirectly to the surge in coca and cocaine production.

It was during this tumult that Colombia elected right wing politician Iván Duque in May. Duque is the protégé of former president and current Senator Álvaro Uribe. Their alliance could impact not just what’s left of the peace agreement but the entire structure of the underworld where, during 2018, ex-FARC dissidents reestablished criminal fiefdoms or allied themselves with other criminal factions; and the last remaining rebel group, the National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional – ELN), filled power vacuums in Colombia and neighboring Venezuela, making it one of our three criminal winners this year. Meanwhile, a new generation of traffickers emerged, one that prefers anonymity to the large, highly visible armies of yesteryear.

SEE ALSO: The ‘Invisibles’: Colombia’s New Generation of Drug Traffickers

Also of note in 2018 was a surge in synthetic drugs, most notably fentanyl. The synthetic opioid powered a scourge that led to more overdose deaths in the United States than any other drug. Fentanyl is no longer consumed as a replacement for heroin. It is now hidden in counterfeit prescription pills and mixed into cocaine and other legacy drugs. It is produced in Communist-ruled China and while much of it moves through the US postal system, some of it travels through Mexico on its way to the United States. During 2018, the criminal groups in Mexico seemed to be shifting their operations increasingly around it, especially given its increasing popularity, availability, and profitability. The result is some new possibly game changing alliances, most notably between Mexican and Dominican criminal organizations.

Among these Mexican criminal groups is the Jalisco Cartel New Generation (Cartel Jalisco Nueva Generación – CJNG), another of our three criminal winners for 2018. The CJNG has avoided efforts to weaken it with a mix of sophisticated public relations, military tactics and the luck of circumstance — the government has simply been distracted. That is not the say it is invulnerable. The group took some big hits in its epicenter in 2018, and the US authorities put it on its radar, unleashing a series of sealed indictments against the group.

Mexico’s cartels battled each other even as they took advantage of booming criminal economies. The result was manifest in the record high in homicides this year. The deterioration in security opened the door to the July election of leftist candidate Andrés Manuel López Obrador. AMLO, as he is affectionately known, did not necessary run on security issues, but he may have won on them, and in the process, inherited a poisoned security chalice from his predecessor. While Peña Nieto can claim to have arrested or killed 110 of 122 criminal heads, AMLO faces closer to a thousand would-be leaders and hundreds of criminal groups.

The rise in the availability of cocaine and fentanyl greatly impacted the United States, which remains one of the world’s largest consumers of drugs. But 2018 showed that the days of the US using drug policy as a foreign policy hammer may be nearing an end. In the run-up to the United Nations General Assembly, for example, the Trump administration’s four-pronged “Call to Action” went largely unanswered by other countries in the region. Canada, meanwhile, legalized marijuana, and Mexico’s newly elected president considered a radical departure from the law and order approach the Trump administration promotes.

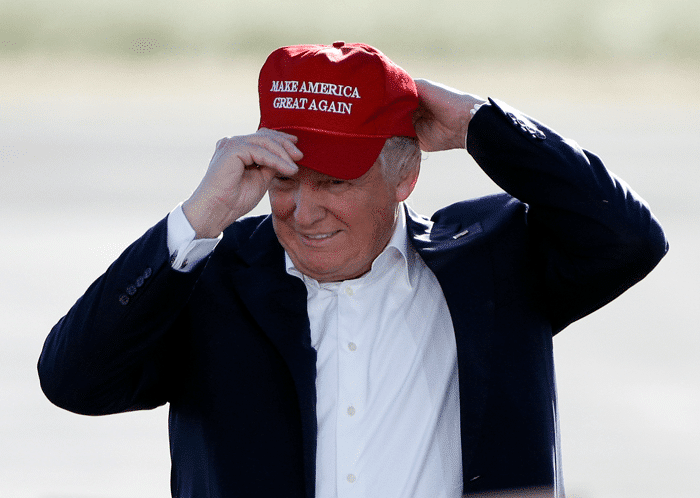

Still, two years of Donald Trump’s strange, haphazard foreign policy has had a devastating impact on foreign relations in the region and has opened the door to transnational organized crime. To begin with, Trump has largely abandoned years of anti-corruption efforts in Central America, while his administration faces near constant accusations of corruption inside his own regime.

Specifically, 2018 will be remembered as the year the US government stopped supporting the International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (Comisión Internacional Contra la Impunidad en Guatemala – CICIG), the UN-backed adjunct prosecutor’s office in that country. During nearly 10 years in Guatemala, CICIG-led cases have imprisoned presidents, vice presidents, vice presidential candidates, former ministers, bank owners, hotel owners, and many more. But this year, current Guatemalan President Jimmy Morales — who is also under CICIG investigation — began lobbying the White House and its allies directly, and eventually succeeded in cobbling together a coalition of accused elites. Morales sidelined the CICIG and exiled its celebrated Colombian commissioner, despite pressure from US Congress to keep the judicial adjunct in the country.

Other presidents, most notably Honduras President Juan Orlando Hernández, has played a similar game and largely succeeded in neutralizing that country’s version of the CICIG, the Support Mission Against Corruption and Impunity in Honduras (Misión de Apoyo contra la Corrupción y la Impunidad en Honduras – MACCIH). In February, Juan Jiménez Mayor, the head of the MACCIH, abruptly resigned. In an open letter published on his Twitter account, Jiménez said he left because of lack of support from MACCIH’s progenitor, the Organization of American States (OAS), and concerted efforts by the Honduran congress to undermine the Mission. In both Honduras and Guatemala, there have also been constitutional challenges to the MACCIH’s and the CICIG’s mandates. But, on a positive note, the re-election of the relatively active attorney general in Honduras may make efforts to neutralize anti-corruption forces there moot, most notably on one investigation that inches very close to President Hernández himself.

None of this seems to bother Trump, who spent 2018 engaged in a near permanent political campaign in the US, much of which revolved around conflating immigrants fleeing criminality with the actual criminal groups going after them, like the Mara Salvatrucha (MS13), something we tackled in our three-year investigation into the gang. Even worse, his administration’s border policies are actually helping organized crime. And his administration seems to have abandoned any pretense of pushing for human rights or a free press, even while the region remains the most dangerous place on earth to be a journalist largely because of the organized crime, corruption, and impunity that US allies like Morales and Hernández foster.

Indeed, Trump’s disregard for law, order and the truth allowed demagoguery to flourish, and nowhere was this clearer than in Brazil, where the rightward turn was even sharper than for its Colombian neighbors. After getting stabbed during a political rally, the military-evangelical populist Jair Bolsonaro — who was often described as a “Brazilian Donald Trump” — surged to the presidency on a racist, xenophobic platform that combined higher prison sentences, militarization of the war on crime, and turning back regional efforts to legalize certain illicit substances.

But if 2018 is any indication, bullying his way towards a more secure Brazil — which saw an astounding record of 63,880 homicides in 2017 — may not be so easy, even if it was a popular solution. The year witnessed another round of fighting in different parts of the country, including a series of battles between the Family of the North (Familia do Norte) and the Red Command (Comando Vermelho), which effectively ended a 3-year pact between the two groups. However, it was the First Capital Command (Primeiro Comando Capital – PCC), which continued to pose the biggest threat, expanding both within Brazil and the region, and putting it at the top of our list of criminal winners for 2018.

Ironically, it was the leftist government of El Salvador that most resembled the militaristic Bolsonaro anti-crime strategy in 2018. The Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional – FMLN), effectively green-lit a hardline strategy that reminds many of the same regimes that FMLN guerrillas once battled against before it turned into a political movement. In 2018, the party also codified its most draconian measures and largely protected the intellectual authors of the most egregious human rights violations, even while the results of these measures remained spotty at best.

Meanwhile, gangs like the MS13 showed their ability to adapt in 2018, and to exert their political muscle in ways that continue to surprise, most notably in the capital city, San Salvador. Here the former mayor, and current leading presidential candidate Nayib Bukele — himself a political chameleon who swapped from the leftist FMLN to a rival centrist party — negotiated with the gangs so he could start reshaping the city’s Historic Center into a more family-friendly — or at least, tourist friendly — area. The approach in many respects worked; as violence was down, the center got some much-needed structural upgrades, and new businesses opened. A drop in homicides this year suggests that the FMLN and other political operators may have also noticed the political results and may be seeking to accommodate the gangs as well in the lead up to the February elections.

SEE ALSO: How to Leave MS13 Alive

Towards the middle of the political spectrum was Costa Rica, which in April elected Carlos Alvarado Quesada of the center-left Citizens’ Action Party (Partido Acción Ciudadana – PAC) as president. There, the election did not seem to turn on citizen security, but the survival of the new president’s administration may. Homicide rates are at record levels, in large part because Costa Rica is playing a greater role in transnational criminal activity, but possibly also because 2018 showed that the country’s security forces may be more deeply involved in crime than ever.

On a political spectrum all his own was Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro, who was reelected in April in an exercise that seemed to confirm that he has long since dispensed with any pretense of democracy. As we chronicled in a multi-part special investigation, Venezuela has effectively become a vehicle for criminal interests. The reasons for this center on the emergence of homegrown criminal groups that are both inside of the government and connected to it; the abdication of the state of its duties especially as it relates to prisons; and the death of any viable economic system to support the corruption and ineptitude that prevail in the Maduro government.

The result was nothing less than chaos in 2018, with thousands of refugees who flowed daily into other countries. The unprecedented refugee crisis brought with it desperation and, inevitably, more organized crime. In short, Venezuela became a regional crime hub in 2018, a place where everything from stolen fuel to teenage girls and rotten food was for sale and every space was open for competition. The government did not seem to mind. It responded by launching a cryptocurrency tied to its failing oil industry, even while the First Lady was fighting off accusations of drug trafficking.

Amid the stark zero-sum political squabbles, there is an outlier, a beacon of hope even. In 2018, Argentina seemed to be searching for some sort of happy medium in the battle against crime. The government made a push to improve data collection and intelligence gathering, while it punched up its arrest and seizure statistics. It has implemented a community policing program, even while it has flirted with using a militarized approach along the borders and elsewhere.

The results are coming in fits and spurts. The dismantling and trial of one of the country’s most violent criminal groups, for example, was upstaged by its continued ability to operate from prison. And a new plea deal law opened a window into official corruption, most notably among politicians connected to the former government of Cristina Fernández de Kirchner.

As Argentina’s Security Minister Patricia Bullrich told InSight Crime in an interview in 2018, the government’s plan is almost perfect. “We set into motion what we call the 80/20 model: 80 percent intelligence, 20 percent chance,” she said.

It was, in 2018, a refreshingly candid remark, an admission that not every program is as advertised.

Credit: Ap Images