On July 7, 2021, a team of mercenaries invaded the home of Haiti’s President Jovenel Moïse and shot him dead. The country was already unstable following a series of natural disasters combined with years of political, economic, and criminal turmoil. But the assassination tipped it over the edge into new depths of crisis characterized by ever-worsening violence.

Today, Haitians face physical and systemic violence in nearly all of its manifestations, and behind much of that violence are criminal groups that have been growing in power and brutality. Below, InSight Crime chronicles the various forms this violence takes.

Gangs

Turf wars between criminal groups such as 400 Mawozo and G9 and Family (G9 an fanmi – G9) have put hundreds of thousands of Haitians in the crossfire.

Gang Violence in Haiti

In this map, each circle represents a violent event committed by a gang. If there were fatalities, the circle is larger in proportion to the number of lives lost. Click a circle for more details about the event.

As gangs have amassed power, their ambitions have grown, as have the atrocities. On September 18, Jimmy Chérizier, alias “Barbecue,” leader of the G9 gang and one of Haiti’s most infamous criminal leaders, declared his intentions of taking over the country.

According to Gédéon Jean, executive director at the Center for Analysis and Research in Human Rights (Centre d’analyse et de recherche en droits de l’homme — CARDH), Barbecue’s statement is incendiary, but not a real threat, at least for now.

“For the moment, a takeover by criminals is impossible,” Jean said. “The gangs are mainly interested in crimes from an economic perspective.”

However, this search for economic returns has been one of the main drivers of violence in the country.

Murder

From 2019 to 2022, homicides in Haiti nearly doubled.

Much of the killing is concentrated in Haiti’s most underdeveloped areas, such as the Port-au-Prince suburb, Cité Soleil, according to data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). But in recent months, the violence has been expanding.

“You had communes such as Cité Soleil where you had known massacres in the past, but we’ve seen an increase in violence in other communes such as Petionville,” Sandra Pellegrini, Latin America Regional Specialist at ACLED, told InSight Crime.

Gang Killings in Haiti

This map shows gang killings in Haiti. Each circle represents a different incident. The size of the circle corresponds to the number of lives lost. Click a circle for more details about the event.

Kidnapping

Kidnappings — long used by gangs to extract ransoms and flex their political influence — have been consistently rising for the last four years and surged following Moïse’s assassination, according to data by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).

Gangs have often allied with Haiti’s politicians, who pay them in exchange for their cooperation and mobilization of votes during elections. But Haiti has not held elections since 2019, pushing gangs to ransom kidnappings to fill the economic void.

Recent cases have shown kidnappers are willing to target high profile individuals — and demand high ransoms for their return. On October 18, Secretary-General of Haiti’s High Transition Council Anthony Virginie Saint-Pierre was kidnapped in Port-au-Prince by men dressed as police. Local media reported that the kidnappers are demanding $2 million for Saint-Pierre’s freedom.

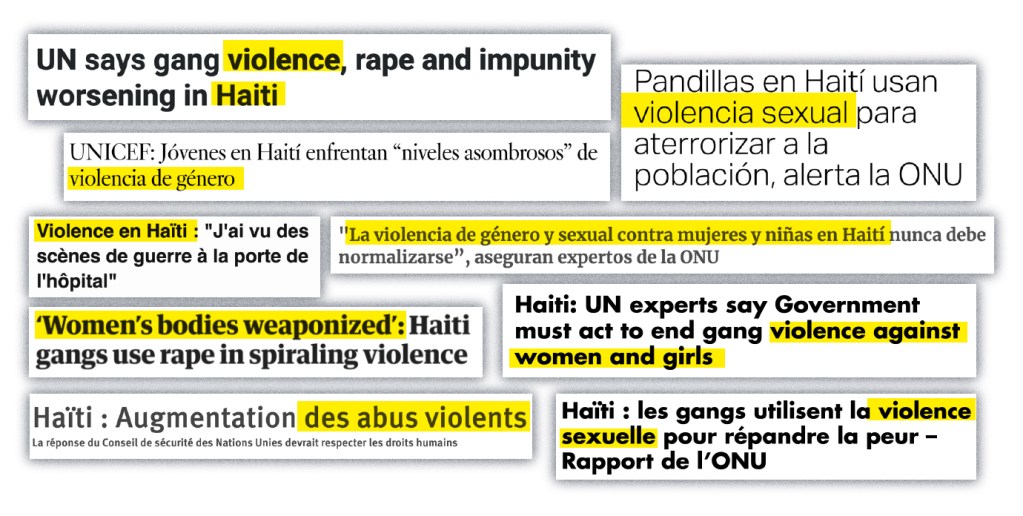

Rape

To control their turf, Haitian gangs terrorize local communities, using the systematic rape of women and girls as a weapon of war, according to the United Nations.

The G9, for instance, has used rape to punish women living in areas controlled by rival gangs. In one horrific example from April, G9 members raped at least 49 women in Cité Soleil. The women were fleeing the violence in a neighborhood controlled by another gang, according to a report by the UN Integrated Office in Haiti (Bureau intégré des Nations Unies en Haïti – BINUH).

“We have a clinic that treats victims of sexual violence. In Port-au-Prince, there are an average of 400 new cases a month,” said a worker with Doctors Without Borders, who spoke to InSight Crime on condition of anonymity.

But any data on gender-based and sexual violence is likely a severe undercount. Even in less chaotic circumstances, this type of violence often goes unreported, and hospital reports only capture instances where medical treatment was both available and sought.

In Haiti, the widespread violence and resulting mayhem make the accurate collection of data on gender-based and sexual violence even more difficult.

“Sexual violence is usually way underreported because of impunity and fear of reprisals,” said ACLED’s Pellegrini.

Displacement

Many people have fled their homes to escape the gang violence.

The number of internally displaced people (IDPs) due to conflict in Haiti rose 430% from 2021 to 2022 — the largest increase Latin America has witnessed since data started being collected in 2018.

In Haiti, 106,000 people were displaced in 2022, more than in more populous countries where large criminal groups operate, like Mexico and Brazil.

SEE ALSO: Was Haiti’s President Moïse Killed for Valuable State Contracts?

Targeting Schools

With gang violence causing massive displacement in Haiti, many people have sought shelter in school classrooms, as refugees in their own country. But when the school year began in Haiti last month, many children could not return to their classes.

Gangs have also attacked schools, stealing school equipment, furniture, and food supplies. According to UNICEF, 72 schools were targeted in the first four months of the 2022 school year, up from eight in 2021.

To protect students, many schools closed. In the month of January, students missed an average of 1.5 days of school per week.

But nowhere is safe.

“We receive children with bullet wounds. There are children who see their homes burned, their houses looted, who see their families possibly raped. So they’re witnessing a level of violence that’s just unthinkable really. I think it’s hard to imagine the level of violence this generation of children is witnessing,” the Doctors Without Borders worker told InSight Crime.

Rising Hunger

Haiti is reliant on imports for 50% of its food, and 83% of its rice, according to the World Food Program. As gangs take over areas, they often block food shipments or impose taxes on those transporting them. Disruptions to irrigation and attacks on Haiti’s agricultural centers are also plunging more and more people into starvation.

Haitians Living in Crisis Level Hunger or Worse

The Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) defines five stages of hunger: 1) Minimal/None 2) Stressed 3) Crisis 4) Emergency 5) Catastrophe/Famine. Every arrondissements has at least a quarter of its population facing Phase 3 crisis-level hunger or worse. In 11 arrondissements, the majority or the population is at crisis-level hunger

Hunger had leveled off before the assassination of Moïse, but has since accelerated. An Integrated Food Security Phase Classification analysis estimates that 1,807,955 Haitians — nearly a fifth of the population — are experiencing emergency levels of hunger.

Impeding Medical Care

The gang blockades have caused shortages of medical supplies. And many doctors and patients, fearing for their lives, have abandoned hospitals and clinics, like in Port-au-Prince’s Carrefour-Feuilles.

On July 6, for example, armed men stormed Doctors Without Borders’ Port-au-Prince hospital, leading to its temporary closure. Security concerns forced the organization to temporarily close multiple hospitals and permanently close their emergency center in Martissant.

The lack of medical care amidst rampant violence is concerning on its own, but Haiti is now also facing a crisis from the spread of cholera, which is nearly absent from the rest of Latin America and the Caribbean.

In the aftermath of a devastating earthquake in 2010, a United Nations camp was responsible for contaminating a river, leading to a cholera outbreak that killed as many as 30,000 people. After going three years without a case of cholera, cases began surging again in 2022. The World Health Organization estimates that there have been almost 60,000 cases of the disease since it reappeared last year, with young children the most affected.